Chile goes VIGNO

(by peter)

Big versus small. It’s a live theme in Chilean wine, and touches many a nerve.

Big versus small. It’s a live theme in Chilean wine, and touches many a nerve.

The Chilean wine industry is often criticised for being highly consolidated, with a few big players and then a smattering of smaller producers. It’s true, despite the fact that the ranks of the artisans are being swelled with every year that passes.

The smaller guys often smart at what they see as the unfair power wielded by the titans of the local industry, whom they say exploit smaller producers by keeping grape prices low and use their political power to hold sway both domestically and abroad. I’ve come across this very passionate resentment on many occasions and sometimes, I confess, have uncharitably simply thought – well, stop whining and do something about it.

And now, just such a scheme has emerged: VIGNO. One of its key protagonists is Andres Sanchez, winemaker at Gillmore in the Maule Valley (and consultant for various others). I’ve had many a heated discussion with Andres of the type described above – he’s a passionate kind of guy, the type it’s hard not to both warm to and respect. Now, under the VIGNO banner, Sanchez wants to support smaller grape producers and champion old-vine dry-farmed Carignan from Maule.

I should add at this point that I’ve been a long-time fan of coastal Maule reds – including those made by Andres at Gillmore. (By way of background, Andres is married to Daniella Gillmore; her father Francisco owns the winery.)

This area is different from much of Chile’s wine lands. It is profoundly rural: sweeping tracts of rolling hills under a vast cloud-specked sky, riven by trenchant rivers and their broad gravelly beds. It is where some of the country’s first vines were planted by European settlers; venerable old vine stocks here are not uncommon. Some of the coastal territory – known as the secano costero – receives just enough rain for the plants not to need irrigation.

The best wines from this area, including those of Gillmore, have a different structural paradigm from the Chilean norm. These reds are racy, red-fruited, with tangy acidity, firm chalky tannins and an elegantly bittersweet finish – reminiscent of an Italianate style. Food-friendly. Ageworthy. Characterful. Ultimately: refreshing, in all senses.

So the problem wasn’t with the local wines per se. It was more in how they were perceived – and presented. Andres was chomping at the bit in his ambition to tell the world about the local wines; the world remained tenderly indifferent.

Until now.

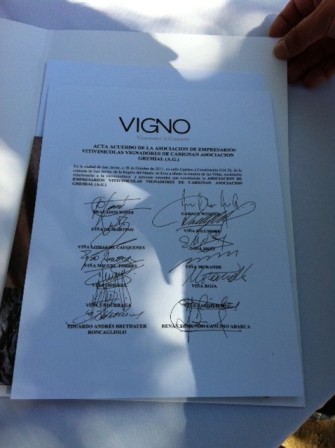

In late October, a pioneering agreement was signed between twelve Chilean wineries to create a new concept in Chilean wine. Call it an appellation, call it a collaborative brand, call it what you will: VIGNO is an ambitious and laudable innovation in Chilean wine which looks set to do exactly what Andres has long desired: put Maule on the map.

In late October, a pioneering agreement was signed between twelve Chilean wineries to create a new concept in Chilean wine. Call it an appellation, call it a collaborative brand, call it what you will: VIGNO is an ambitious and laudable innovation in Chilean wine which looks set to do exactly what Andres has long desired: put Maule on the map.

The rules are as follows. In order to be able to label a wine with the VIGNO trademark, producers must:

- Use a minimum of 65% Carignan in a red wine, with the balance being made up of old-vine varieties from the Maule secano zone

- All Carignan vines must be old, ie 30-years-old or more – or be plants grafted over rootstocks of the País (Mission/Criolla) variety themselves 30-years-old or more – located within Maule’s secano.

- All vines must be dry-farmed (ie unirrigated)

- The wines must be aged for at least two years before being released for sale (the manner of this maturation is not specified)

‘For me, it’s the most significant innovation in recent Chilean wine history,’ Sánchez proclaims midway through an extensive interview. ‘Twelve producers reaching a consensus, deciding to self-regulate and create a common image: it’s a quantum leap – and what’s more it’s replicable elsewhere in Chile for those who want to make wines of representative local character.’

He adds, ‘the idea is to raise a flag to say: here we can make local wines of world class’.

The emphasis on Carignan stems from the area’s local history.

This variety, commonly found in Spain and France’s rural south, arrived in Maule in the early 20th century. After the devastating earthquake of 1939, the Chilean government incentivised the planting of Carignan to help stricken growers by improving the quality of the local reds based on the insipid País variety with Carignan’s deep colour, tangy acidity, firm tannins – not to mention its ability to yield plentifully.

This variety, commonly found in Spain and France’s rural south, arrived in Maule in the early 20th century. After the devastating earthquake of 1939, the Chilean government incentivised the planting of Carignan to help stricken growers by improving the quality of the local reds based on the insipid País variety with Carignan’s deep colour, tangy acidity, firm tannins – not to mention its ability to yield plentifully.

However, Carignan’s popularity eventually waned due to the drop-off in yield as the plants matured and its susceptibility to oidium (powdery mildew). In many cases the vineyards were simply abandoned. Others were farmed in lacklustre fashion, the grapes sold for a pittance.

Then, in the mid-1990s, as Chile’s wine industry went into over-drive to service burgeoning international demand, a few forward-thinking wine people saw the potential of these old-vine stocks and began to make wine from them. One of the first was Francisco Gillmore under the Tabontinaja brand.

Many have since followed, including wineries based elsewhere but keen to champion local Chilean specialities: winemakers like Marcelo Retamal at De Martino, Arnaud Hereu at Odfjell, Rafael Urrejola at Undurraga and Pablo Morandé.

Sánchez estimates that there are now around 600 hectares (ha) of Carignan in Maule, almost all of which dates back to the 1940s incentivised plantings. (The official SAG figures show around 450 ha in Region VII, comprising Curicó and Maule, so this might be a slight over-statement. However, the SAG data aren’t always accurate and certainly won’t account for mixed plantings, in which old-vine Carignan is often found.)

The genesis for VIGNO came when Sánchez gave an interview to Chilean journalist Eduardo Brethauer in 2008. As Sánchez notes, ‘my travels around Italy, as well as my curiosity and endemic non-conformity, led me over the years to want to produce wines of character which paint a picture not only of the land but also the local people and culture. After all, that’s what wine should be.’

The genesis for VIGNO came when Sánchez gave an interview to Chilean journalist Eduardo Brethauer in 2008. As Sánchez notes, ‘my travels around Italy, as well as my curiosity and endemic non-conformity, led me over the years to want to produce wines of character which paint a picture not only of the land but also the local people and culture. After all, that’s what wine should be.’

Both men became enthused by the potential of old-vine Maule Carignan to, in Sánchez’ words, ‘raise the profile of the secano zone, a profoundly rural area, rich in culture and tradition – in a way, to use Carignan to rescue this place’.

Local growers are already feeling the effects of the rising demand – the price per kilo for old-vine Carignan used to be 150 pesos (around 19 pence or 29 US cents). Now it’s over 400 (50 pence or 77 US cents).

‘It’s a social opportunity for the people,’ explains Sánchez. ‘These producers have survived repeated crises by subsistence farming, abused as they are by the economies of scale of the big wineries who buy grapes at rock-bottom prices to use in their cheap wines. It’s an important change to the local economy.’

VIGNO – a shortening of ‘Vignadores de Carignan’ – is an attempt to put a recognisable name and face to this phenomenon. Sánchez describes it as, ‘the first real appellation in Chilean wine’ and, in certain respects, he’s right. No other Chilean appellation has rules in place regarding viticultural practices, varietal usage and maturation – which are common features of European appellations. Chilean wine law is primarily about geographical delimitations and labelling practices.

But are such regulations necessarily a good thing? And how will they work?

In putting the second question to Sánchez, I asked what checks and balances were in place to protect against sharp practice, as well as potential sanctions.

In putting the second question to Sánchez, I asked what checks and balances were in place to protect against sharp practice, as well as potential sanctions.

He responded that a technical team had reviewed and verified all member wineries’ practices. They are also setting up tasting panel to taste new wines. Sanctions for non-compliant wineries include disqualification from the association and a ban on using the VIGNO name. A clear geographical delimitation exists for the Maule secano.

While there is no maximum yield in place, Sánchez notes that, in reality, these old vines have naturally low yields in the region of three to four tons per hectare.

When asked, as one of the prime movers of this initiative, if there was any rule he was keen to implement that went by the wayside, Sánchez immediately identified bottling in the region (embotellado en origen). ‘Bottling in the region is not only essential for high quality wine,’ he says. ‘Having a permanent presence in the region also helps interpret the vines better and the wines have even more local character.’

He soon saw he would have to give this one up, ‘or I’d be virtually on my own!’ (Many of the member wineries are based outside the region; the full list is: Bravado, De Martino, Garage Wine Co, Gillmore, Lomas de Cauquenes, Meli, Miguel Torres, Morandé, Odfjell, Undurraga, Valdivieso, Viña Roja.)

Chile, along with other New World wine countries, has long championed its relative freedom from the bureaucratic red tape which afflicts Europe.

However, to my mind one of the chief disadvantages of this kind of liberal regulation is that it allows – even encourages – growers to follow the whims and vagaries of the market, a strategy that ultimately priorities short-term thinking over long-term value and identity. Ultimately a successful wine-producing country needs a bit of both: some freedom to cater for the lower end of the market as well as some fine-wine identity and long-term value. VIGNO is an attempt to bolster the latter in Chile.

Chile is at a stage in its vinous development where it is finding its voice. It has gone from whispering subservient platitudes in the ear of a dominant market to declaring its unique credentials in increasingly strident fashion.

Chile is at a stage in its vinous development where it is finding its voice. It has gone from whispering subservient platitudes in the ear of a dominant market to declaring its unique credentials in increasingly strident fashion.

In this context, VIGNO is a thoroughly welcome innovation. Its progenitors deserve congratulation and recognition (are you listening, President Piñera?!) Yes, it may not be perfect – no nascent system ever is. It may not be for everyone – no appellation ever will be.

But the fact that it has been instigated by – and for – producers, to champion a local product of great cultural value, all within a sensible framework, means it has rock-solid credentials and, one hopes, a bright future. While Chile shouldn’t tie itself up in red tape, some voluntary regulation does make sense in some cases – and VIGNO is a great example.

As to whether the model is replicable elsewhere in Chile, I think other producers will be taking in a keen interest in seeing how this initiative plays out. I asked Sánchez which areas and grape varieties in Chile he thought might benefit from adopting this kind of initiative.

‘There are lots of places – anywhere the vine is naturally stressed, which allows it a particular expression unique to a group of producers. For example, coastal areas could make a Sauvignon Blanc with a particular point of difference – maybe barrel fermented, or with extensive skin contact – something that makes it a bit messy and different, so people remember it and love it, rather than it just being another fresh, simple, anonymous Sauvignon Blanc!’

It’s an exciting thought. In the meantime, I am looking forward to trying the VIGNO wines soon – which I will report on in due course. In the meantime, you can find below a few recommendations of Carignan-based Maule wines which are well worth your while.

POSTCRIPT: on 4th Feb 2012, the estimable Jancis Robinson wrote at length and with characteristic clarity about VIGNO in her Financial Times column. You can read her FT piece by clicking here. She later – kindly – tweeted the link to this piece, describing it as a ‘great perspective on this interesting new Chilean initiative’.

Undurraga T.H. Carignan 2008, 14% (£11.50, Wine Society) – a striking blend of Carignan from Cauquenes and Loncomilla which is scented and plush, with a beguiling succulence and a delicious crunchy concentrated core. Superb stuff. 8/10

Odfjell Orzada Carignan 2008, 14% (from £13.99, independents including Bacchanalia, hangingditch, York WInes) – from the same stylistic school as the Undurraga, this shows a lovely scented, inky nose full of blue and black fruit, crushed flowers and creamy oak. Big, spicy and tight-knit on the palate, taut, with juicy black fruit acidity. Very impressive indeed. 8/10

Odfjell Orzada Carignan 2008, 14% (from £13.99, independents including Bacchanalia, hangingditch, York WInes) – from the same stylistic school as the Undurraga, this shows a lovely scented, inky nose full of blue and black fruit, crushed flowers and creamy oak. Big, spicy and tight-knit on the palate, taut, with juicy black fruit acidity. Very impressive indeed. 8/10

Louis-Antoine Luyt Empedrado Carignan 2010, 12.9% (£12.35, Les Caves de Pyrène) – from a resolutely non-conformist French winemaker based in the rural wilds of Maule comes this strikingly honest wine. Glossy dark fruit with earthy, herbal hints and a touch of floral character. Almost edges into Pinot Noir territory. Juicy, earthy and spicy on the palate: resonant and raw. Long. Very different to the big, bruising style so often the norm with Maule Carignan. A touch dirty and rustic but even manages to make this into a virtue. 7.5-8/10

De Martino El León Carignan Single Vineyard 2006, 14.5% (£14.95, Wine Society) – toasty, elegant and glossy, this is a seamless wine that has the singular virtue of not trying too hard to be something it’s not. Smooth, dense and succulent. 7/10

Morandé Edición Limitada Carignan 2008, 14.5% (£13, Laytons Wine Merchants) – creamy, raisiny dark fruit with floral hints – engaging. On the palate it’s spicy, tight-knit and taut, full of dense, layered concentration. Big and bold – heavy but impressive. 7/10

Bravado Facundo 2007 – a blend of 50% Carignan with 25% Cabernet Sauvignon and 25% Petit Verdot sourced from the Maule, Itata and Colchagua Valleys. An eclectic blend with a spicy, mouth-filling character. Not as good as other wines in Bravado’s portfolio, but decent nonetheless. 6/10

Meli Carignan 2008, 13% – a blend featuring 10% Cabernet Sauvignon, this wine shows wild red fruits together with chalky tannin and a refreshing, lively finish. 6/10

(Note: my thanks to Andres Sánchez for his time, information and also for providing many of the images that accompany this piece.)