- Chile Wines of the Year 2024

- Hunter Valley: History to High Jinks

- Life or Death? On Wine and Health

- Chinese Wine: What’s the Deal?

- Your Ultimate Guide To Wine Faults

- Portugal’s Great Whites

- The Vines of the Future

- WINES OF THE YEAR 2024

- Lessons in Wine Chemistry

- Don’t Know the Great Southern? You Should

- Margaret River Finds its Voice

- Why Wine Matters

- Appellation Marlborough Wine

- Wine in a Can – Sacré Bleu!

- RIDGE – The Insider’s Guide

- Do You Need More than One Wine Glass?

- Fake Wine: A Laughing Matter?

- News & Views 2025

- Battle of the Bubbles

- ‘Adrenaline rush’: Wine Auctions & Trends with iDealwine

- AO YUN – The Insider’s Guide

- Essex: Class in a Glass

- There’s Prosecco – and there’s Conegliano Valdobbiadene

Summary

Ridge is an iconic wine producer – not just in its homeland California, but in global terms too.

But how and why did it attain this status in just 70 years?

Is it really true their policy has been never to hire a trained winemaker?

What is this ‘pre-industrial winemaking’ they champion?

How have they managed to successfully buck the trend for opulence in California Cabernet?

Which of their wines (whisper it) don’t we like?

And can you really be great at both Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel, two grapes seemingly at opposite ends of the red wine spectrum?

Answers to all these questions and more feature in this treat of a show to mark Wine Blast’s fifth birthday (yay!)

We hear fascinating insights and stories from Ridge Chairman Paul Draper as well as head winemaker John Olney before diving into Ridge’s wines, including a vertical tasting of Lytton Springs Zinfandel back to 1976.

(A Monte Bello Cab from 1977 pops up too…)

These are wines that make you smile – then make you think.

We hope Wine Blast performs a similar kind of magic!

Starring

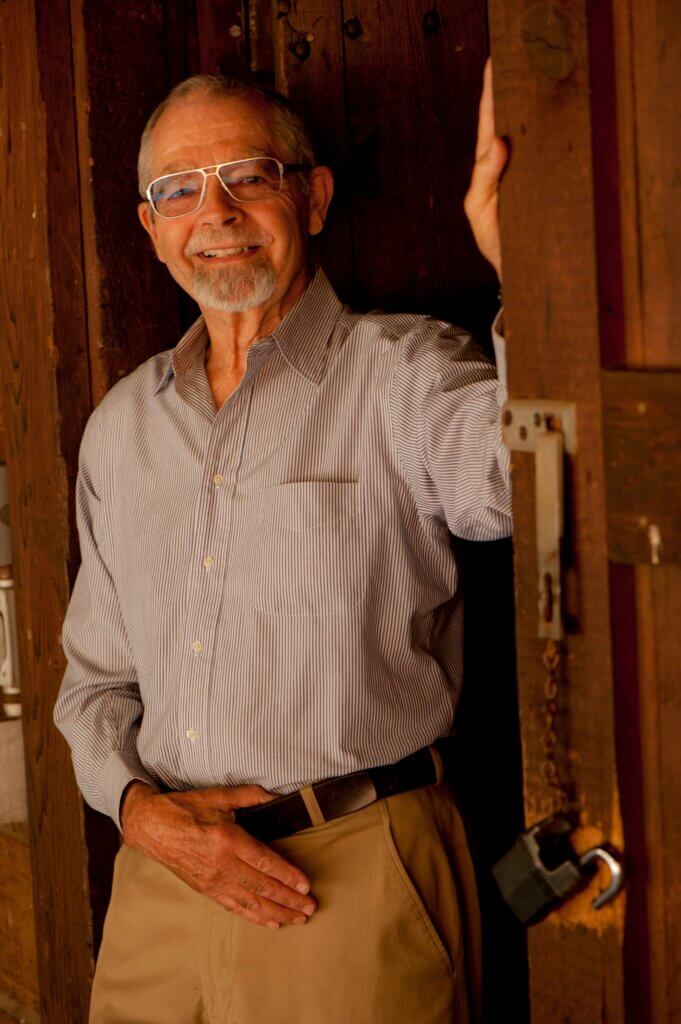

- Paul Draper, Ridge Chairman

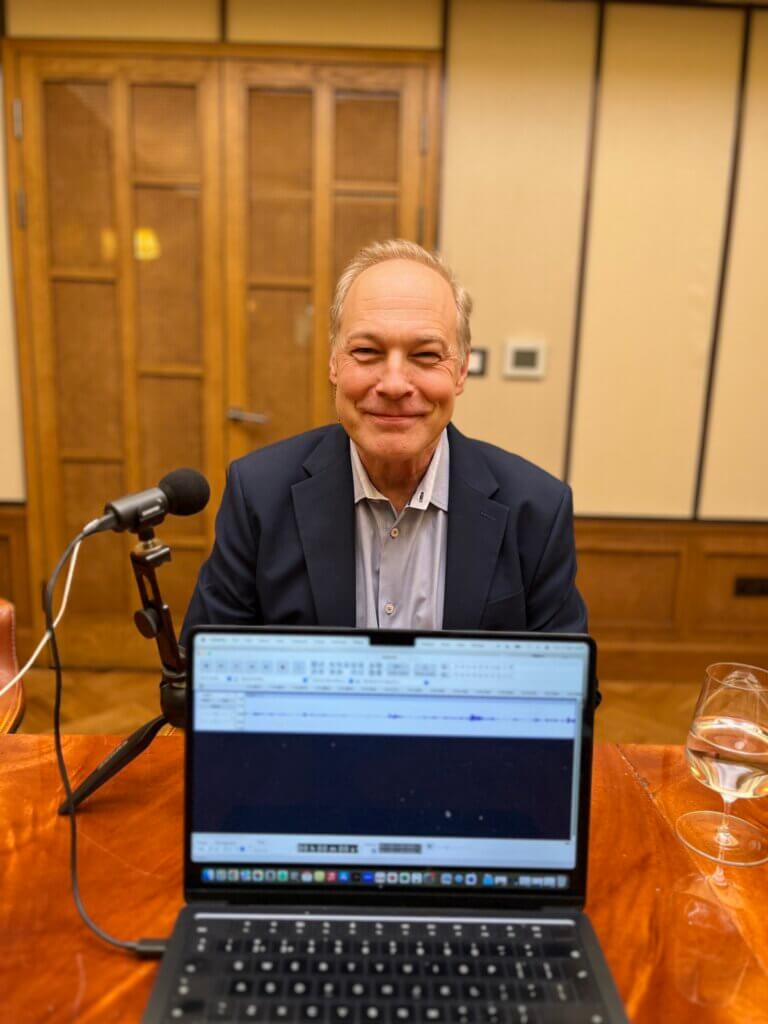

- John Olney, Ridge Head Winemaker

- Susie & Peter

Links

- You can read some of our tasting notes on back Ridge vintages by using our search bar function (at the top of the page)

- As promised in the episode, here’s the link to Paul Draper’s fascinating essay on ‘pre-industrial winemaking’

- You can find our podcast on all major audio players: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Amazon and beyond. If you’re on a mobile, the button below will redirect you automatically to this episode on an audio platform on your device. (If you’re on a PC or desktop, it will just return you to this page – in which case, get your phone out! Or find one of the above platforms on your browser.)

Wines

These are Ridge wines we tasted in March 2025 (apart from the Monte Bello 2009). They all come highly recommended.

Selected UK stockists are provided – for other places, please check Wine Searcher or similar. Ridge does export to quite a few markets round the world so it’s pretty well distributed.

- Ridge Grenache Blanc 2023, Paso Robles, 14% (£44, Highbury Vintners)

- Ridge Three Valleys 2023, Sonoma County, 14.6% (£36, Nickolls & Perks)

- Ridge Geyserville 2022, Alexander Valley, Sonoma County, 14.5% (£52.15 Lay & Wheeler, £60 Laithwaites, £63 Tanners, £61 Highbury Vintners)

- Ridge Lytton Springs 2022, Dry Creek Valley, Sonoma County, 14.5% (£60 Laithwaites, £52.15, Lay & Wheeler, £59 VINVM, £61 Highbury Vintners)

- Ridge Estate Cabernet Sauvignon 2022, Santa Cruz Mountains, 13.5% (£100, Amps Wine Merchants)

- Ridge Monte Bello 2009, Santa Cruz Mountains, 13.5% (£400, Fine & Wild – NB new vintages from The Wine Society)

Get in Touch!

We love to hear from you.

You can send us an email. Or find us on social media (links below).

Or, better still, leave us a voice message via the magic of SpeakPipe:

Transcript

This transcript is AI generated. It’s not perfect.

Susie: Hello, you’re listening to Wine Blast with Susie and Peter – and boy, do we have a show for you! This one is all about Ridge, the iconic California wine producer that not only makes some of the finest wines in the world, it also has an intriguing story behind it.

Peter: Yes, hello! We cannot wait to get stuck in because we’re getting privileged access at, one of the planet’s top wine estates. And we’re taking you with us! Here’s a taster of what’s coming up:

Paul Draper: And I realised, my God, when you have vineyards and grapes of that quality, you need none of these modern techniques. What I would call industrial winemaking.

John Olney: Wine should taste real. It should taste like it comes from someplace.

Susie: The magisterial Paul Draper, Ridge chairman, and head winemaker John Olney there. And I, for one, am very excited to hear more insights and stories from these wine superstars. In due course, we’ll also be rating and recommending some of their sensational wines, including highlights from a unique Lytton Springs tasting back to 1976. Plus a Monte Bello Cabernet from 1977 might be popping up at some stage.

Peter: Yes, yes, yes. Cannot wait. It’s all very special stuff, maybe even a bit more special than, than usual. and there’s a reason for that. Because this is the five year anniversary of launching this show. It’s. It’s a Wine Blast birthday!

Susie: It is indeed.

Peter: So we thought we’d spread the love with this treat of an episode. It’s a sort of cherry on the Wine Blast cake, as it were. And by way of indulgences, it’s not a bad one, eh?

Susie: The very best. I’ll take Ridge. Any birthday you care to nominate. So, yeah, I mean, this profile ties into our Insider’s Guide series where we go behind the scenes at the world’s finest wine producers. To be clear, this is not sycophantic fangirl stuff. Quite the opposite. We want to use this access to ask the big questions, to root around for skeletons in closets so we can tell the story in a way that’s fresh and revealing and hopefully a bit of fun too.

Peter: For example, Ridge is one of the most famous names in wine, but how and why did it get there? You know, the story involves more delightful serendipity than you might imagine. Is it really true their policy has been to never hire a trained winemaker? What is pre industrial winemaking? And can you really be great at, both Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel, two grapes, seemingly at, the absolute opposite ends of the red wine spectrum.

Susie: Then there’s questions like, how has a wine like Monte Bello Cabernet been so successful while brazenly flouting the overwhelming California stereotype of big, rich, showy cabs and defying the American critics who’ve championed opulence and pilloried restraint? You know, what are the hallmarks of Ridge’s style, approach and ownership that have enabled it to thrive? And while we’re at it, what do they make of Trump?

Peter: Answers to all these questions and more are coming up. But first we should set the scene. and it’s fair to say, you know, we have been fans of Ridge for some time now, isn’t it? I think that’s fair.

Susie: Oh, definitely.

Peter: I mean, seriously, card carrying fans,

Susie: How could you not be?

Peter: I know, we’ve been lucky enough to taste their very fine Cabernets and Zinfandels quite a few times over the years, among other of their wines. Sometimes blind, sometimes for work, sometimes for fun. and we’ve always been struck by how they managed to pull off what I describe as a unique magic trick. And that is to seamlessly combine intellectual stimulation with visceral joy. you know, in other words, these are wines that get you thinking and they get you smiling, you know, head and heart in a way that very few wines do.

Susie: Yeah. Now, we’re going to get into detail about the wines towards the end of the show, but it’s fair to say we were intrigued by Ridge from early on in our wine careers, as you’re, as you’re intimating. So when we got to visit in 2011, it was like a pilgrimage for us, you know, driving out of Silicon Valley up that steep mountainous ridge south of San Francisco Bay with stunning views and a breezy, crisp feel at the top. Despite the bright California sunshine, you feel straight away you are in a very special place.

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. And I’m sure that was the feeling that Osea, Perrone had. You know, he was a doctor of Italian descent and opera lover, incidentally. Used to have apparently amazing opera themed parties. he established the Monte Bello winery in 1885 at 800 metres altitude on the ridge.

00:05:00

Peter: Things fizzled out with Prohibition, but the vineyard was revived in the 1940s by theologian William Short, before the property was acquired in 1959 by four Stanford Research Institute engineers working in computer science. And they were Dave Bennion, Hugh Crane, Charlie Rosen and Howard Ziedler.

Susie: Now, there was no grand plan. These guys just wanted a weekend getaway as a back to nature break from the virtual realities of work. High touch and high tech, they called it. they clocked what was a slightly dishevelled Cabernet vineyard and thought they’d give it a go for a bit of fun. And you know what, the wine wasn’t half bad. In fact, the 1960 and 1961 Monte Bello cabs were so good that the partners rebonded the winery in 1962. Serendipity was becoming commercial reality.

Peter: You know, they realised pretty soon that if the winemaking venture was going to work, they’d need more wines to sell. back then, much of California was actually Zinfandel, so that’s what they started selling alongside the Cabernet. More on this in a bit. in their efforts to professionalise, they also hired a winemaker. And in 1969, Paul Draper joined the team.

Susie: But this wasn’t just any ordinary winemaker. Paul Draper was, in his words, a romantic who’d got the wine bug. Aged 16 in New York City, where a Swiss school friend’s family fed him a daily diet of European literature and fine Burgundy and Rhone, he decided there and then he wanted to be a winemaker.

Peter: Only problem was he was terrible at chemistry. aren’t we all? So he knew he would never make the grade at, ah, UC Davis winemaking school. he ended up graduating in philosophy at Stanford and decided to teach himself wine different way. firstly by tasting the classics. You know, first growths and top Burgundy were actually quite affordable back then. Around 20, $25 per bottle in the 70s apparently. Oh, gosh, you know, think back, he says, Paul says, those were my mentors. Great mentors, eh? and the second stage of his wine education was reading the classics, albeit, you know, in this case the lesser known wine book classics. People like Rixford and Boireau, who’d been writing in the 19th century and who advocated what might traditional or old school winemaking. Paul says, my training really was in tasting what is fine wine and reading about technique.

Susie: Now, as for practical experience, he’d done the odd internship, even popping into Chateau Latour at one stage to chat with the winemaker. But his real stroke of luck came in Chile, where he’d gone to work on community development in the idealistic and freewheeling 60s. Along with a friend, he’d spotted the potential in Chilean wine. So, ever the early adopter, he up shop producing old vine Cabernet in coastal Itata down in southern Chile.

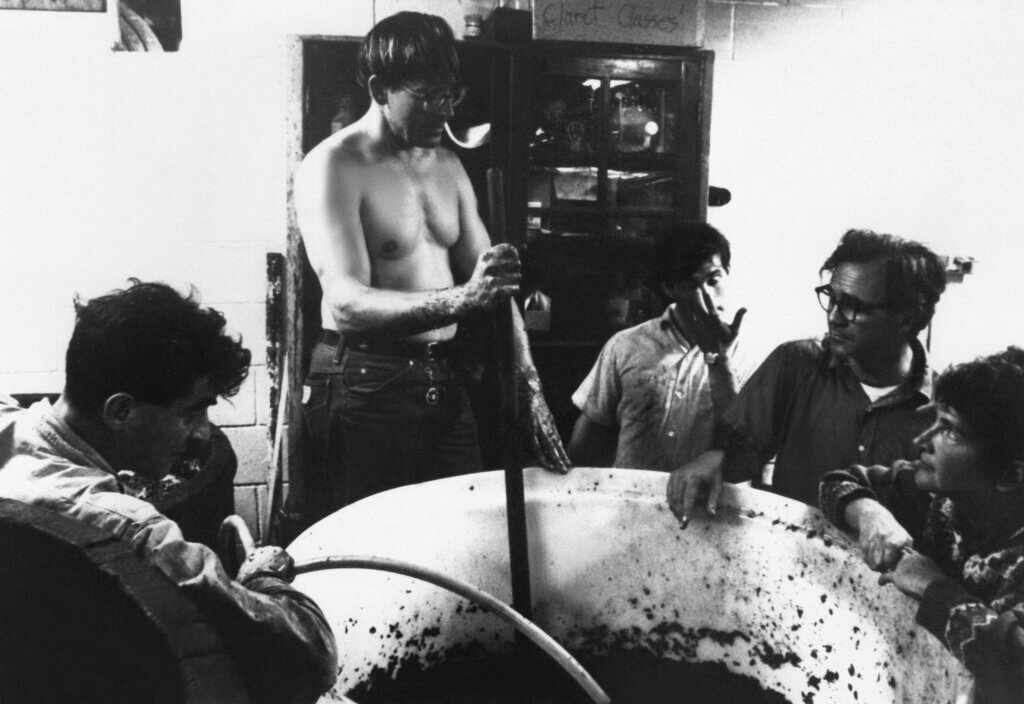

Peter: Now, the winemaking was rudimentary at, best. I think we use that word, Draper Talks about using open lagars manual de stemming and buying oak staves from a parquet floor company to make barrels. but it worked. he apparently still has some bottles of this wine, this Chilean wine from the early 60s, and they have been likened in quality by a few people to Monte Bello

Susie: I can’t believe that.

Peter: More importantly, it taught Draper that you didn’t need a fancy enology degree to make great wine. In fact, that might actually limit your capacity to make great wine if it prioritised standardised techniques over creative intuition. And incidentally, this is a policy that Draper and Ridge have pursued since.

Susie: Now, chile in the 1960s was conflicted. This was a time of Salvador Allende and shortly after, Augusto Pinochet. So Draper returned to California and, as luck would have it, gave a talk about his winemaking experience in Chile to a small group, one of whom was David Bennion, who happened to be looking for a winemaker at Ridge. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Peter: Draper has now been with ridge for some 56 years and counting. The man is a wine legend. he earned his spurs in the 1976 judgement of Paris, where California wines beat the most vaunted names in French wine. Ridge’s 1971 Monte Bello Cabernet came a very creditable fifth head of Chateau Leoville Lascases, among, other names. he was even more chuffed when the same wine in the 30th anniversary rerun of this landmark tasting in 2006 came first in both tastings in Napa and London.

Susie: Along with the wine side of things, Draper had also managed something quite rare in wine successful corporate ownership. He’d quietly overseen the sale of Ridge to Japanese company Otsuka Pharmaceuticals in 1986, a successful partnership that persists to this day. More on this in a bit.

00:10:00

Peter: Yeah. He’d also ensured succession and the continuity of Ridge’s unique philosophy. Winemaker John Olney joined Ridge in 1996, and as Draper was stepping back, John became head winemaker in 2021. Now, in his 90th year, Draper remains fully immersed in the world of Ridge, describing himself as a very active chairman. I think we know well, that kind of thing reads. Tasting very regularly, helping with the blends, editing labels, joining meetings and generally keeping everyone on message. When I spoke to Paul, the conversation was typically stimulating and wide ranging. And it wasn’t long before we were talking about a memorable bottle of 64 Lafite. That’s 1864 Chateau Lafite Rothschild, the famous Bordeaux first growth.

Paul Draper: I look back to the end of the 19th century, to the techniques that were making the wines in that era. And, in fact, the finest wine of my life was a 64 Lafite that we bought from Christie’s, from Glamis Castle, from the Queen Mother’s estate. And after 100 years, we had had no sign of fading in the least, and was the most beautifully developed, in a sense, feminine wine, but still had its structure. And I realised, my God, 100 years out, because of the techniques that were used to make that wine. Look at the complexity and the longevity. And I said, okay, that’s it. What were they doing back then? I read a guy named Boireau from Bordeaux who wrote, two volumes in 1877. And I then read further from that era and said, okay, these are the techniques that we’re going to use. And believe it or not, though, that lack of additives, that lack of processing, the limited approach, but very careful that they were doing in those days is exactly what I brought to Ridge. And those are the techniques that we use today that John uses to, to make the Monte Bellos. And that hasn’t changed.

Peter: So you term this approach pre industrial winemaking. What does that mean? on a practical level,

Paul Draper: Put it this way, we now have a minimum of 60 additives that are accepted in Europe, South Africa, Australia, certainly California. And we also now have amazing number of processing machines, all of these to improve the quality of the fruit that comes to the winery and to make something that the public will find more pleasant to drink. And the trouble with it is that all these additives and all this processing machinery is basically to take either mediocre or average quality grapes and make them into a wine that is better, that tastes better, that is more appealing to the public than it would be without them. The trouble is that in teaching those techniques as, ah, what would I call it, the tool belt the winemaker has, he thinks that’s what you, that’s what winemaking is. And whether you have excellent or great grapes, you still use, to one degree or another, some of those additives and processing. And the point is you do not need them. When you have grapes of excellent, great or great quality, you do not need any of that to make great wine.

Peter: What do you need to make great wine then?

Paul Draper: You need a vineyard that produces grapes when properly handled, that is, obviously, you need the experience of the vigneron in the vineyard to really know what he’s doing and taking care of the soil, not just the vine. And, that those vines then produce not only high quality But a distinctive quality that can separate them out from other vineyards to a degree, depending on the vintage and all of that, but that really have their own character over time that you can follow that distinctive character. And when you have vineyards and grapes of that quality, then you need none of these modern techniques. What I would call back to your question. industrial winemaking.

Peter: Now, you differentiate your style of Cabernet from most producers in Napa. Because of course these days, Napa famously tends to be a very rich, ripe style of Cabernet. Whereas of course, back in the day they were making wines which are much more moderate than alcohol and very different in style.

Paul Draper: Oh, there were just some beautiful wines I can think of what would have been about 76 or so Shafer,

00:15:00

Paul Draper: I mean, just world class wines. I mean really. And, and to go from that to overripe wines, where you lose the complexity, you lose the acidity, where you end up just with very ripe fruit and you don’t have the, liveliness, the freshness that you get when the grapes are properly ripened.

Peter: Do you think this style is set to stay? I mean, would you say that this is still a style which is very endemic, very prevalent in Napa in the US?

Paul Draper: Well, I’d say that of course the US population since 97 has been brought up on those wines. And so people who are not, have not been or are not, tasting European, wines may, have this prejudice. And problem is that maybe until this recent turndown, basically those high end wines at very expensive prices have continued to sell. And so why should they change? We say, if it isn’t broken, why fix it? And so, yes, I think dominantly that style is still the style, but many younger winemakers really are looking. And of course I can pick a not so young, but wonderful winemaker, Cathy Corison, and the style that she’s made all these years and has not changed with the Napa style of not using, not, waiting for the grapes to overripen. So I think there is movement in that direction. I think the top sommeliers push to the degree that they can to just try to influence it. But in the end, if the public is buying those high priced wines in that style, it’s going to take some time before the whole idea swings back.

Peter: And obviously your style of Cabernet is very different to that. What makes, Paul, for you, a truly great Cabernet Sauvignon in terms of what you want to taste in the glass?

Paul Draper: Well, I’ve mentioned some of the adjectives. so I mentioned freshness, I mentioned complexity, longevity, depth, all of those elements.

Peter: Ridge could be described as a rare example of corporate ownership in wine that’s actually worked. Can you just very briefly tell us about the Otsuka company, how they got involved and how that’s evolved?

Paul Draper: Yes. I joined, the three partners and their families when I became winemaker in 69. And it was just a wonderful relationship. And I joined because of the quality of the 62 and 64 they had made, but also because of the families and how much I like them as individuals. But come the 80s, the majority of the founders really did want to step back and be able to help their kids with purchasing a home and so on. And so, we were looking for someone, who could, we’d be, that would do what we wanted them to do. it was a time when wineries were not selling and it was a downturn really in the whole market. The people interested in purchasing were Hiram Walker and Seagram’s, the two biggest distillers in the world. And into this mix, we had two partners that had joined us earlier than I did who were in the pharmaceutical business and they were doing, joint ventures and licencing arrangements with Akihito Otsuka, who was, had become president of his family’s company. And they asked me if they might tell him that we were for sale. And was he just. No, because he had always said how interested he was in what we were doing. And he was a great lover of Bordeaux and a good taster. And so he came down and visited and we tasted and actually we then went to dinner and I served him the 70 Mouton and the 70 Monte Bello blind. And given, that he is this samurai, his team was really upset that I was putting him on the spot. And actually his top guy I had said in, as we sat around my living room, California wine has none of the complexity, none of the finesse of a great Bordeaux. And I said just as strongly, you’re wrong. Monte Bello has every bit as much finesse as a great Bordeaux. And Akihito. Mr. Osuka clapped his hands. Yes. And so I think that was one of the moments that

00:20:00

Paul Draper: interested even more in, in the whole idea of working together. I took him to dinner and, and I gave him blind, the 70 mouton, the 70 Monte Bello And he tasted them and he said, I don’t know California wines, but this is clearly the Bordeaux and this is just an, an excellent wine. its Complexity, its longevity. I mean, it’s length. He said, this must be the Monte Bello. And I said, yes, it is. And. And before that, his, top innovator and taster had already said to me, I was wrong. This wine has every bit as much finesse as Bordeaux. So at that moment, that sealed it, and he, decided that he would take over Ridge. So that he then said, we will never discuss finances unless you’re in terrible straits. I just want to come, every year, walk the vineyards, and taste the wines with you. And we’ve done that for. We did that for 30 years until his death. And his son and his company have continued their absolute commitment to Ridge. So he never had the company interfere in any way with the decisions that we were making. So it was just an ideal relationship, and, allowed us to grow, further. we basically stopped growing in 99, and we. Since 99, we have remained at this at a steady state of where we were then. And, we feel that with the vineyards, we have to do what we want to do and to enjoy it to the degree that we’re all enjoying it, we, want to hold it at that level and just focus on pushing the envelope.

Peter: Now, you guys do a very good line in food matching. suggestions on your website. Can you paint us a picture of how the great Paul Draper would enjoy a great bottle of Cabernet or a great bottle of Lytton Springs Zinfandel?

Paul Draper: Doesn’t matter. Sure. I’m one of those that feel that Cabernet goes best with lamb. Having done, once, years ago, extensive tastings with Zinfandel Cabernet and cuts of beef and cuts of lamb. That Zinfandel is ideal, with beef. And, that really, for me, cabernet and lamb are the match. And so, Oh, I don’t know. I would say Tagine. it’s got to be because of the fact that Monte Bello though it can be approachable as a younger wine, really is not going to show its full complexity and what it has to show until, oh, a minimum of 15 years. And I would even love to go more like 20. So that would be the wine that I would be matching with the course. And of course, I would have. I would have had, a good Chardonnay, a good vintage of Chardonnay to begin the meal. And if I were able. If I were still standing, I might even go so far. Well, I normally, as much as I love our essence, I probably would have, a really fine bottle of Sauternes.

Peter: What does the future hold for California wine and for Ridge Paul?

Paul Draper: For us, much, more so than the rest of the industry, say, in Napa. Export is very important to us. And so the immediate problem is what our president is doing, in terms of tariffs and alienating, our, markets. In the long run for California, I think the style will change. I think we have not been as affected by climate change, well, especially at Monte Bello But there’s no question that unless we can, altogether begin to reverse, climate change, in the end, I fear for the quality of fine wine. Wine, yes, Grapes, yes. That can adapt to higher heat. But I honestly do not see the quality level of Pinot Noirs that are made today or bored over idols that are being made today being matched by other varietals, that are more adapted to warm climate.

Peter: Paul Draper, thank you very much indeed.

Paul Draper: Peter, thank you. This was a delight.

Susie: Oh, that vision of the great Paul Draper tucking into a 20 year old Monte Bello with lamb tagine and they’re

00:25:00

Susie: getting wobbly, finishing off with Sauternes. Brilliant.

Peter: Just love that.

Susie: I know. I also love that story about him serving the, the 70 Mouton and Monte Bello blind. I mean, it was a pretty gutsy call with a lot riding on it, wasn’t it? Yeah, you know, high risk wine poker. But, you know, he believed in himself and the wine despite being told he was wrong. And it worked out pretty well. You know, the whole corporate ownership thing, as Paul says, has been brilliant for them. And it’s meant the wine world has retained a jewel in its crown.

Peter: Absolutely, absolutely. And, you know, I’d also pick up on Paul’s dogged championing of, you know, what he terms pre industrial winemaking. You know, it’s absolutely key to what Ridge does and why it’s done so well. To my mind. You know, it’s set out as an essay on Ridge’s website and I’d urge any aspiring winemaker to read it. In fact, anyone interested in wine to read it. It’s fascinating, you know, and personally, I wish more winemakers around the world could train themselves by reading the classics and tasting the classics, then kind of prioritising their vineyards and making wines of elegance and character. You know, it’s perhaps not a cheap or an easy option, but, you know, as we see with Ridge, the results can be amazing.

Susie: Yeah, I mean, it was, it was interesting, wasn’t it, what he was saying about the trend for what he terms over ripeness in California wines, particularly Napa Cabernets. You know, he cites the very warm 1997 vintage and the influence of critics like Robert Parker for shifting the dial towards that style, which clearly does sell and remains the accepted norm. But, you know, while there’s room for all tastes and styles in wine, we definitely agree with Paul. You know, we’d, we’d also question how long this trend for opulence over elegance can really last. You know, overripeness gives fairly monochromatic wines easy to understand, but also easy to get bored of. You know, they don’t sit particularly easily with food. They don’t tend to age and develop well. even when they have stratospheric prices and they often have high alcohol, meaning you can only drink a small amount of them.

Peter: Yeah. And then you compare them with something like Ridge’s Cabernets, which are very different in style. They are refreshing and they’re poised and they’re able to age and develop into things of beauty, you know. And I know which style, I think has legs to last the course. I know which style we prefer. You know, when we visited, Paul said to us, and I love this quote, very, understated. Our perception of full ripeness here is radically different from Napa, because of course, both of them would term it optimal ripeness. They’re very different things. And what Paul said was balance is the key.

Susie: Yeah. There was another great story he told us about making a Napa Cab, as he said, to try to show Napa what they could do better. it was the, the, the 1971 Isley, which had 12.9% alcohol. And Paul describes it as, and I quote, in its own way, the equal of the 71 Monte Bello And that’s saying something given the accolades that wine has had.

Peter: Yes.

Susie: And he says the Isley aged beautifully too.

Peter: Yeah. So a lovely Napa Cabernet, maybe Restraint low alcohol has aged beautifully. Made by Paul. Yeah. And when we went to Napa, if you remember, you know, and tasted the Mondavi cabernets in the 80s, you remember doing that, you know, they were, they were great. They were beautiful. Yeah, absolutely beautiful. You know, and Paul did talk about the old Inglenook and La Cuesta wines, which showed him that California really could do top notch Cabernet to rival Bordeaux. But that approach had been lost with the emphasis on modern winemaking and chasing the fashion for ultra ripeness.

Susie: I also can’t help but love the fact that Ridge, one of the great American wineries, one of the great wineries of the world owes a fair bit not only to serendipity, but also to Chile. You know, if Paul hadn’t gone to Chile and ended up making wine there, we may never have had Ridge as we know it today.

Peter: A telling little detail. Love that. On that note, I think it’s time to take a quick break before we come steaming back with head winemaker John Olney on Zinfandel, old vines and real wine. plus some top Ridge tips from us by way of brief recap so far. Ridge is a proud producer of world class California Cabernet and Zinfandel, whose resolute insistence on old school winemaking and ambition for finesse has made them one of the most celebrated names in wine. But it hasn’t all been plain sailing. a fair bit of good luck, even a bit of wine poker, has been involved, as has a fearless commitment to bucking the prevailing wine trends and sticking to their guns.

Susie: So we’re going to bring in John Olney, now head winemaker since 2021. John’s story is an intriguing one. his uncle was the food and wine writer Richard Olney, and one of John’s formative experiences was joining Richard

00:30:00

Susie: in Provence when he was writing a book on the iconic Burgundy estate Domaine de la Romanée Conti, or DRC.

Peter: As you do.

Susie: As you do. So the young John got to taste more than his fair share of DRC, much more than I do today, he jokes. And that must have made quite an impression, mustn’t it?

Peter: You know, we’re back to the importance of reading and tasting, aren’t we? I think two things which are really under undervalued in wine, today in winemaking. You know, John says that that experience instilled in him, and I quote, a sense of terroir, that wine can transcend a grape variety. now, John did study winemaking in Burgundy, so it’s not entirely true that Ridge has never hired a trade winemaker. and he also worked with Gerard Chave in the Rhone and Aubert de Vilaine at DRC. And he did a spell with celebrated US Wine importer Kermit lynch, too. All formative experiences before he joined Ridge in 1996, subsequently becoming Lytton Springs winemaker for 20 years after the term of the millennium.

Susie: Now, you caught up with John, didn’t you, in London, before a monumental tasting of Ridge wines, including the vertical of Lytton springs, back to 1976? We’ve already mentioned, and we should preface this interview by explaining that Lytton Springs is, along with Geyserville, possibly Ridge’s most celebrated Zinfandel. It’s an old vineyard. Some vines date back to 1901 in Dry Creek in Sonoma county, which is sunny and warm, but also with a definite moderating cooling influen from the Pacific.

Peter: Now, crucially, it’s not pure Zinfandel like Geyserville. It’s an old mixed planting. And the Lytton Springs wine is a field blend incorporating carignan for acidity, petite sirah for tannins and alicante bouschet for kind of colour and earthiness. John says this is the key to balance and also the unique character of this wine. anyway, back to the interview. sommeliers were busying themselves around us prepping for the tasting as we chatted. And I asked John on what had struck him when he first arrived at Ridge back in the late 90s.

John Olney: You know, what, what was, amazing for me at Ridge was just how hands on everything was and the way in which, you know, everything was being done one wine at a time. Everything was being done by taste. so it was, a great alternative to the more technical, approach of winemaking where, you know, you see people with a lot more clipboards and trying to get a lot more control over things. So I was really impressed by the way that Paul seemed to have this, I guess, what I call sort of this trust and faith in sort of the natural process.

Peter: Because, you know, the winemaking at Ridge has been described as pre industrial winemaking, hasn’t it? what does that mean exactly?

John Olney: Yeah, you know, and for me, I guess, you know, I think, you know, Ridge was really a pioneer in California in, seeking out, you know, special places and making single vineyard wines and that sort of belief that if you have the right vineyard, if you have the right raw materials, then you don’t need to get in and fiddle around with it too much. So by pre industrial, you know, we always said that we’re, we’re happy with the raw ingredients and the less that we do, the more authentic a wine we feel we get. It’s sort of starting at that point where let’s let the natural process, let’s give it a chance, shall we say, as opposed to, you know, I think there’s often, a distrust in that and a feeling that, you know, you’re really throwing caution to the wind and, you know, you’re sure you’re going to come up with a wine that is just has all of these off flavours and aromas and won’t be sellable and, you know, so. And that’s kind of, I guess that’s more like fear based winemaking, I would.

Peter: Say, because you say about your wines, you want them to truly express the place.

John Olney: Yeah, yeah. I mean, you know, wine should taste, it should taste real. It should taste like it comes from someplace

Peter: Well, let’s talk about that and tell us and the place. Tell us about Monte Bello

John Olney: Yeah, so Monte Bello I mean, it really is special. I mean, m. You know, it’s, First of all, it’s on a mountain. It’s just very rugged, country. And, the soils are quite unique. It’s one of the few places in California that has quite a bit of limestone in the soil. there’s a quarry right at the base of the mountain and at the top of the ridge, which is where we get the name. If you look out west, you’re only about 12 miles from the, the Pacific Ocean. And that really has an important factor on the climate because, you know, I can say the Pacific Ocean has very, very cool breezes. And it sort of acts like an air conditioner over the, over the, vineyard to help it keep it a little cooler. So we get, we get ripeness at, you know, sort of slower rates and it allows us to make a wine that generally

00:35:00

John Olney: is lower in alcohol, than most other regions of California. I, think that gives us this wonderful balance and natural acidity, which is one of the reasons I think, the wine ages so well. So it’s quite a unique spot.

Peter: John, what makes a truly great Cabernet Sauvignon?

John Olney: I think what makes any great wine is that the grape varietal of the clone, the rootstock, has to be matched to the soil and the climate. I think it comes down to picking the grapes at the right time and treating the grapes in a way that you end up from the beginning with a wine that has balance.

Peter: And what about a tasting note? What would be a tasting note of a great generic Monte Bello Ridge, Monte Bello Cabernet. What would you smell and what would you taste?

John Olney: Just, well, you know, starting with the aroma, you know, you do get that kind of cassis, plum, BlackBerry fruit. there’s a certain, certain minerality to it. and of course, when it’s young, because we do age our wine or all of our wines, but Monte Bello is the only wine we age in 100% new oak. So there, you know, there’s definitely that American oak, aroma Present. And then, you know, again, I think the textural quality of the wine is very important. So I think that you want to have some tannic grip, but. But overall, it should be a fairly sensuous, experience. And that great acidity, that kind of makes the whole thing very tight knit and kind of holds it together. and then that nice long finish, those are the key elements, I think.

Peter: I’m salivating. Let’s talk about Zin, then. you have many different sites across Sonoma. Well, across California, really, but Sonoma particularly, you know, where you’ve got Zinfandel planted. How well does Zinfandel express terroir or site expression?

John Olney: it’s a great question. I came back to California after spending time in France, and particularly in Burgundy, and I was interested in winemaking. I hadn’t really signed up with anyone at that point. And, you know, all my friends said, oh, well, you know, you’re going to make Pinot Noir, of course you’re going to make Pinot Noir. and I was interested in Pinot Noir. I still am. But what I found was that in so many cases, Zinfandel really is, you know, to me, it seems like it expresses the given place in so many different corners of, California that it was, I think. And that’s why I think Zinfandel has become the grape of California. Of course, it didn’t originate in California, but it’s found its home in California, you know, And I think that’s. That’s what’s so magical about, you know, Zinfandel is, you know, you can have it planted at Lytton Springs, you can have it planted over in Sonoma Valley, or in Paso Robles. And you get these. You get these slight, subtle differences that just makes it very interesting.

Peter: Tell us a little bit about Lytton Springs.

John Olney: Yes, I mean, you know, Ridge is, Again, a little bit of, you know, necessity breeding, you know, the mother of all invention. When the original founders had, started making, you know, just a few barrels of Cabernet at Monte Bello in the 1960s, they immediately set out to start replanting the vineyards and being able. Able to expand their production. in the meantime, they said, well, we need to do something for cash flow here. So let’s go out and we’ll search other parts of California and we’ll buy some more Cabernet. But in the 60s, certainly before the 60s, going all the way back to the 19th century, pretty much the vast majority of vineyards in California were planted to Zinfandel. So that’s what they found. They found all these old vines, vineyards which were, Zinfandel. And they began purchasing from different vineyards. And then over time we really found that there were a handful of vineyards where we really thought they were just a cut above, they were exceptional. And one of those vineyards was Lytton Springs in Dry Creek, in Sonoma, County. And, in 1972, Paul Draper met the owner of the vineyard. No, no one had ever made the wine as a single vineyard. He saw the vineyard, he said, we’d love to take these grapes and made, the wine. And it was, it just had this darkness, this earthiness, this complexity to it that sort of made it a mainstay almost immediately for Ridge. And we’ve been making it, you know, ever since.

Peter: Now, you, you grow a lot of. Old vines, particularly Zinfandel. How important are, old vines? Or rather, what, what do they give to a wine?

John Olney: I think that, you know, for me, I think the most important thing with old vines is, and especially the Zinfandel, which is a very vigorous, grape, varietal. As the vine gets older, just like us, you know, the metabolism slows down, so it begins.

00:40:00

John Olney: The yields sort of self limit themselves. You know, you, you have Zinfandel is when it’s young, it is, it’s a grape that has a main cluster and then it will have this big shoulder hanging off. And when it’s young, it’s almost like there’s two clusters in one, you know, and we usually have to go out and cut that shoulder off. By the time you get to a vine that’s 60, 70 years old, you know, there’s. There’s barely even that second cluster at all. So now you’re dealing with much smaller yields, usually smaller berries. So you’re getting more concentration. I think that’s, for me, that’s probably the biggest, the biggest factor.

Peter: Interesting. You specialise in single vineyard wines, finding, exceptional sites, as you say, where climate, soil and variety are all well matched. How is climate change affecting that matrix for you now? And what are you, how are you reacting to that?

John Olney: Yeah, so, you know, no question it, you know, we see harvest happening earlier and because, you know, everything we do at Ridge is still all, hand harvested. You know, the importance of having more, pickers ready to go so that we can get the grapes in, in a shorter amount of time has become paramount. You have to be much more surgical about it. Certainly when we talk about Zinfandel I think were in terms of managing or absorbing, if you will, the heat. I think we’re actually fairly well positioned in the sense that with older vines you have deep root systems. and also all of our Zinfandel, vineyards are head train, you know, bush vines, goblet, which, you know, we’re feeling rather a bit smug now because, you know, what’s wonderful about the about head trained vines is you get this, this shading, so you’re getting that dappled light. Whereas when you’re up on a wire, you know, in vertical shoot positioning, you know, you’re much more exposed to the sun. And you know, in these late afternoon heat spells that we have, you can really, you know, your fruit can just get, you know, sunburn right on the vine. I mean, having said that, you know, the other thing that’s, it’s almost more the unpredictability that we see, that’s, that’s much more, you know, at hand. I mean, perfect example was in 22, we had a very short condensed harvest, and then 23, we had one of the longest, most drawn out harvest. We were harvesting Zinfandel into November. So it’s these big swings that make things, you know, a lot more. That’s kind of the biggest challenge not knowing, you know, what, what your getting into in any given vintage.

Peter: So talking about climate change, do you think, I mean, is there a scenario which you, you can see replanting varieties or looking to new areas perhaps to develop?

John Olney: Absolutely. I think, I think that represents, in a lot of ways, I think it represents a great opportunity, you know, in California and really in many places, if the same mentality that’s brought to, you know, what should we plant in the vineyard today, which, you know, is generally revolves around, well, what do we think is going to sell? had that been the approach back in the 19th century, we wouldn’t have Zinfandel, right? We wouldn’t have Zinfandel, we wouldn’t have these field blends. So, you know, I think we have to really bring that, a little bit more of an open mind to what we plant in terms of, well, what’s going to work. And once we kind of figure that out and experiment with a few things and we find something, then we can, you know, let’s have the confidence that that will sell. Right? As, as opposed to just sorting. Well, it’s got to be Cabernet, it’s got to be Chardonnay. I think a great example of that, is down to Paso Robles, where, white, White wine has never been. It’s always been a very small part of what we do, and it’s always been limited to just the Chardonnay. It’s that we grow at Monte Bello And, you know, we had the opportunity to buy some Grenache Blanc from down in Paso which, by the way, is also one of the few places where there’s quite a bit of limestone in the soil in California. And you know, I was a little dubious to tell the truth. I’ve never read from, you know, say, from the Languedoc and places like that where it, you know, I find it can often be a bit of a heavy and somewhat of a, you know, kind of a flabby wine and not, you know, so I was like, ah, this might not. But it turns out that it really is a great place to grow that grape. even in that pretty hot climate, it maintains acidity. We harvest it and we’re able to produce it, you know, around 13% alcohol. It has great expression of fruit. And it also fits a spot for us where it’s a little lower priced and it’s very different from tropical Chardonnay. So that’s been, you know, that, that’s. I think that’s a real, that’s a success story. you know, and it’s interplanted with a little bit of Picpoul which I think really helps that acidity.

Peter: But, just going back to the Cabernet and Chardonnay thing, do you think, I mean,

00:45:00

Peter: do you think this is the time for California to start looking beyond those, those, you know, very marketable, very bankable, but maybe quite ubiquitous grapes and actually go into slightly more niche areas and say, well, if this works here, let’s make it work commercially.

John Olney: I, I think so. I think at a very bare minimum, if you think about it, the wonderful reference book Wine Grapes by Jose Vouillamoz and Jancis it’s sort of limited to 10,000 vinifera varieties that we still know are planted somewhere, however few, acres it might be. So the possibilities and the permutations have there, you know, are just, mind boggling. And we live in this, this tiny bandwidth of Pinot, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay and Cabernet.

Peter: So anything particularly esoteric you, you got your eye on that you might like to try out?

John Olney: Well, I mean, I think that I think there’s opportunities perhaps in things like Grenache and Tempranillo that would make. Seem to make sense on paper. So could. Are worth exploring a bit more, you know, so that comes to mind. And I also think that there’s, you know, there’s probably some other white varietals, maybe Albarino, things, like that that could be very interesting for, you know, California soloist and climate.

Peter: What does the future hold, both. For California wine and for Ridge?

John Olney: I think that we are going to see quite a bit of change in California as well as other regions too, in terms of what we were talking about before. I think we’ll start to see, different wines being produced, you know, and then at Ridge, I think we’re. We’re certainly going to, try to keep doing the same thing, but better, you know, be the way to put it.

Peter: Simple. Best things are often simple, aren’t they?

John Olney: Yeah.

Peter: John, thank you very much indeed.

John Olney: Absolutely. It was wonderful. Thanks so much.

Susie: Ridge is essentially just gonna keep on being Ridge. I really hope so. But interesting what he said about how California might start changing or perhaps how it should look to change.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. And talking sustainability, you know, in terms of carbon emissions, he mentioned they’ve lightweighted their bottles, which are now 460 grammes rather than 570 grammes each. And Monte Bello of course, is not a stupidly heavy bottle. Unlike some other stellar California wines. It’s. It’s the same bottle as the Zinfandel. So, you know, and on the commercial front, they’re very aware of the trend to people drinking less but better. Hence they’re focusing on quality and what John describes as the connection to the earth.

Susie: yeah. One other thing Ridge is famous for is putting ingredient lists on their back labels. This isn’t usually obligatory for wine, though the EU is now introducing a requirement for a QR code. but Ridge has had this on their bottles loud and proud for quite some time. Frankly, it was a reaction to what they describe as the industrial winemaking used elsewhere, with people using mega purple and enzymes and all kinds of other things. So their labels tend to state hand harvested organic grapes, indigenous yeast, oak from barrel ageing.

Peter: Yeah, Amongst a few other things. But, yeah, it’s really interesting they do that. And, you know, John’s an advocate for all wine having ingredient lists, because he says it will likely become a legal requirement at some stage in the future, and it’s better to get ahead of the game and kind of control the narrative. but also, I guess, you know, promote transparency and responsible winemaking. and talking of ingredients to move on. I also asked John about food and wine Pairing. And he had some great advice for an older Monte Bello Cabernet. He says, keep the food simple to let the wine shine. Love that. Love that. So, you know, he suggests something like a subtle cheese platter, you know, I quote, not Munster with Monte Bello to be clear, which would be a crime against humanity, I think. or you suggested exactly something just like ribeye and potatoes with Monte Bello cafe. He says it doesn’t have to be anything too fancy, anything that might take away from the wine.

Susie: Yeah, that’s so true. now we’re going to come on to the wines, but just before we do, it’s hard to talk about anything US related without touching on current politics. Some Canadian friends of the pod, for example, are finding it hard to engage with US wines given the Trump administration’s policies. But of course, many American wine producers are opposed to what Trump is doing, Ridge among them. So you asked John about the impact of Trump’s policies.

John Olney: One of our top export countries is Canada. So if you want to talk about a direct negative, impact, there’s your evidence. And if you’re rounding up the people who represent some of the only people who are willing to pick grapes, and send them away, that’s, you know, it’s going to make things even more difficult for us. I also question there’s many countries who have legitimately hostile,

00:50:00

John Olney: relationships with their neighbours. We have wonderful neighbours to the north and to the south. So why, why poke the bear if it’s not even a bear?

Peter: I also asked Paul Draper the same question.

Paul Draper: Everyone is most concerned because of the fact that the programmes that most affect, the poor, the disadvantaged are the ones that are being cut, that so many people are going to suffer. I think we’re headed for a constitutional crisis. I personally am optimistic that, whatever it takes to get through that and to bring back the balance of power within the government will, happen. many people are not. It’s a real time of crisis.

Susie: Some sobering thoughts there. So let’s move swiftly on to the much more palatable subject of the wines. And I think, I think we should start not with Monte Bello where the winery is based and the famous historic Cabernet Gros. We’ll come on to all that posh stuff in a bit. I think we should start with the Zinfandels and some, some current releases.

Peter: You know, I think you’re absolutely right to start there. Ah. because, you know, I think we often think of Ridge primarily about their great Cabernet. Don’t we. But actually their zins and, you know, other things are just as worthy of attention and are drinking headspace as it were, you know, particularly, you know.

Susie: Yeah.

Peter: Because for me, their best Zinfandels are precisely the wines that capture this sort of incredible intersection of fun and seriousness, of kind of winning hearts as well as minds and, you know, they’re things of beauty.

Susie: Yeah. I mean, let’s start with the two we have here, both 2022 vintage, the Geyserville and Lytton Springs. the latter of which is their 50th anniversary bottling. So another birthday to celebrate. They’re a little more mature in every sense than our five year pod.

Peter: Fair enough.

Susie: But both, both are gorgeously attractive, inviting wines. both are field blends. The Geyserville is 62% Zinfandel, 20 Carignan and 10% Petite Sirah with 3% of Mataro or Mourvedre. And it is floral and fruity and open and lifted. I think you can hear the joy in my voice. And you’ve got flavours of. Of blueberry and almond friand and really easy going. So appealing, but with just enough fine tannin to really ground it as well, you know, Silky smooth, I think. Impossible not to love. It’s just joyful, isn’t it?

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. Sorry, I’m just so joyful I can’t stop sipping it. So the next one, you know, the Lytton Springs, it’s got a touch more Zinfandel in the blend, sort of 67%, I think, this one, then 19% Petite Syrah, 11% Carignane and 3% Alicante Boucher. And it’s kind of a bit darker, a bit sort of firmer, a bit more earthy and herbal and meaty than the Geyserville. And it’s quite sort of mysterious and brooding in a way. I don’t know if you’d agree with that. It’s sort of. Yeah, yeah, You’ve got that mysterious, you know, and it’s a touch of gingerbread there too. But the key thing here is that the tannins are definitely firmer and more intense in a lovely way to balance the kind of natural fruit richness and that herbal, meaty, smoky kind of tobacco complexity. It’s just a really complex and layered wine as well as being quite succulent and moreish. It’s just a compelling combination. Just sort of another level.

Susie: Yeah. I mean, so John describes the difference as if Geyserville is more burgundy, Lytton Springs is more Bordeaux and I didn’t know when we were tasting that he’d said that, but I did myself find myself saying that the texture and structure of the, the Lytton Springs is more Cabernet like than the fruitier, easygoing generosity of the Geyserville. Anyway, they’re both about 60 pounds, which is not cheap but very fair value for what are surely some of the best Zinfandel based blends in the world. And they can age too, can’t they?

Peter: They sure can. Thanks for taking that up. You know, so, you know, the tasting we did in Lytton springs back to 1976 really showed how well balanced, carefully made wine can age, even if it’s based on Zinfandel. You know, it’s a famously generous, wine with tonnes of IM appeal. But here at Caneig, you know, we tried 10 vintages. My favourites were the really seductive 2015, the kind of very gastronomic 2010, the sensuous 2007, and then the haunting sous bois tones of the 1989, which was really mature. And I think the general consensus among our staters was that the sweet spot for ageing Lytton Springs was around the 15 year mark. But this is definitely a wine that can be drunk young or fully mature as well.

Susie: Yeah, and it’s interesting to see the proof in the glass of what John was talking about that Zinfandel can and does make different styles of wine in different places, which very much vindicates Ridge’s approach of focusing on single site wines and prioritising character and elegance and

00:55:00

Susie: age worthiness. and just to clarify here, the reason Ridge can make top Zinfandel as well as top Cabernet is that these varieties are grown in different places. You know, Monte Bello is a high, cool ridge south of San Francisco Bay in the Santa Cruz Appellation. These Zinfandels come from warm but moderated sites further north in Sonoma county. And each variety is well matched to its site, as John says, and Ridge very much respects that.

Peter: Now, before we come on to talk about the Monte Bello and Cabernet, we’ve got a couple more current releases here, haven’t we?

Susie: Yes.

Peter: First of which a, white wine is one John mentioned, the Grenache Blanche 2023 from Paso Robles or Paso Robles, which has incidentally 14% Picpoul and 2% Roussanne in the mix. Now, we both fell in love with this wine straight away, didn’t we?

Peter: We did.

Peter: It’s so characterful and generous. It’s got a lovely dollop of oak, but also very balanced and refreshing and grounded. You know, if Lytton Springs were a white wine, it would taste something like this. No, just. Just gorgeous.

Susie: I mean, it would be so hard to pick this wine blind, wouldn’t it? It’s just so unique. It’s got this sort of gorgeous cinnamon brioche aromas and then kind of spritzy, bruised red apple flavours. And so impressive in its own very specific style. And without wishing to be critical, we would definitely choose this over their Chardonnays, wouldn’t we? Which.

Susie: Yeah. They’re nice, but sometimes a little bit rich and sweet fruited. For us, you know, Monte Bello to our mind, is better for Cabernet.

Peter: Yeah, I’d agree, I’d agree. talking of Cabernet, the. The current ridge Estate Cabernet 2022, formerly the Santa Cruz Mountain Cabernet, is typically glorious with a kind of fresh cassis and creamy oak scent. Floral hints, fine firm flavours, sleek and complex and layered, ultra fine tannins. you can drink it now, you can age it if you want. This is a beautiful wine to buy if you can’t quite afford Monte Bello like most of us, but you want a seriously stylish, nice, elegant California Cabernet.

Susie: Yeah, I mean, we’ve had old vintages of the Estate Cabernet sometimes alongside Monte Bello and it definitely holds its own, so we’d. We’d heartily recommend that one. As for the Monte Bello it’s just a beautiful expression of Cabernet, well, actually of a Bordeaux blend, because there’s usually around 25% merlot, plus a bit of Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot in the mix. And this is a wine that’s all about texture and nuance, isn’t it?

Peter: Yeah, yeah. The tannins, I think, are what sort of stand out the most. They’re usually pretty firm, but also ultra fine. So you get this wonderful combination of kind of gastronomically, elegantly drying texture with layers of fruit and spice. It’s sort of quite beautifully rugged, for want of a better term. you know, you notice the American oak with its creamy coconut tones when the wine’s young, and then it kind of mellows into to sweet tobacco and spice as the wine ages. There’s often a kind of earthy, almost ferruginous edge to it. And again, it appeals on an intellectual level, but also on an emotional level, too.

Susie: Yes. So so we tried the 1977, didn’t we, at the IMW symposium back in 2023, which was gloriously evocative, you know, with its tobacco, dried fruit, roasted pepper, warm earth and cedar aromas, but then still very firm tannin, rugged, savoury, elegantly drying texture, you know, very long, very fine. I think almost rocky. Was your, what, your note on it, wasn’t it? And then just seamless on the finish.

Peter: Yeah. And then we’ve, you know, really enjoyed a few other vintages over the years. And it’s always distinctive and self assured as a wine, you know, invariably with assertive but fine tannins, often with that creamy headness, floral edge, but always complex, age worthy, you know, and fresh. you know, some favourites include the 1990, 95, 2007, 2009. And then at the Lytton Springs tasting, we had an imperial of the 1999, which was pretty special too.

Susie: Did you now? Did you now?!

Peter: It was all hard work.

Susie: And you mentioned freshness there. Something that Paul put his finger on too. It’s such a key aspect of fine red wines that’s often slightly glossed over, but you need it for structure, for refreshment value, to be able to pair with food and to make a wine age worthy. And it comes from the climate and sight. I, I do remember slightly shivering on the top of the ridge when we visited.

Peter: I remember that too. Yeah, I think I had to give you a jacket anyway, shivering, as I say it. Paul did say that sometimes, you know, they actually have to de-acidify the odd tank of wine they have. That’s how cool their site is. But it gives you an idea of just how much on the cusp of ripeness they are. And that’s where the beauty is with great Bordeaux blends.

Susie: So I think that’s where we should wrap things up. By way of closing summary, Ridge is a very

01:00:00

Susie: special wine producer. Serendipity may have played a role at the start. Good fortune and hard work have certainly been part of the story since over time, Ridge has honed the art of, of crafting wines that make you smile then make you think. they are champions of single site, expressive wines made using old school, non interventionist techniques. They’ve been magnificently fearless in eschewing the trends for overripeness in California. Above all, Ridge is Ridge. It’s steadfast consistency, a beacon of joy in a fast changing world.

Peter: Thanks to our, interviewees, Paul Draper and John Olney, and thanks to everyone, who’s made this episode happen. wine. Details and links will as ever, be on our website. Here’s to good things standing the test of time. Thanks for listening. Until next time. Cheers!

01:00:52