- Season 7 Trailer

- The Jancis Robinson EXCLUSIVE Part 1

- The Jancis Robinson EXCLUSIVE Part 2

- Chile Wines of the Year 2025

- SAN LEONARDO – The insider’s Guide

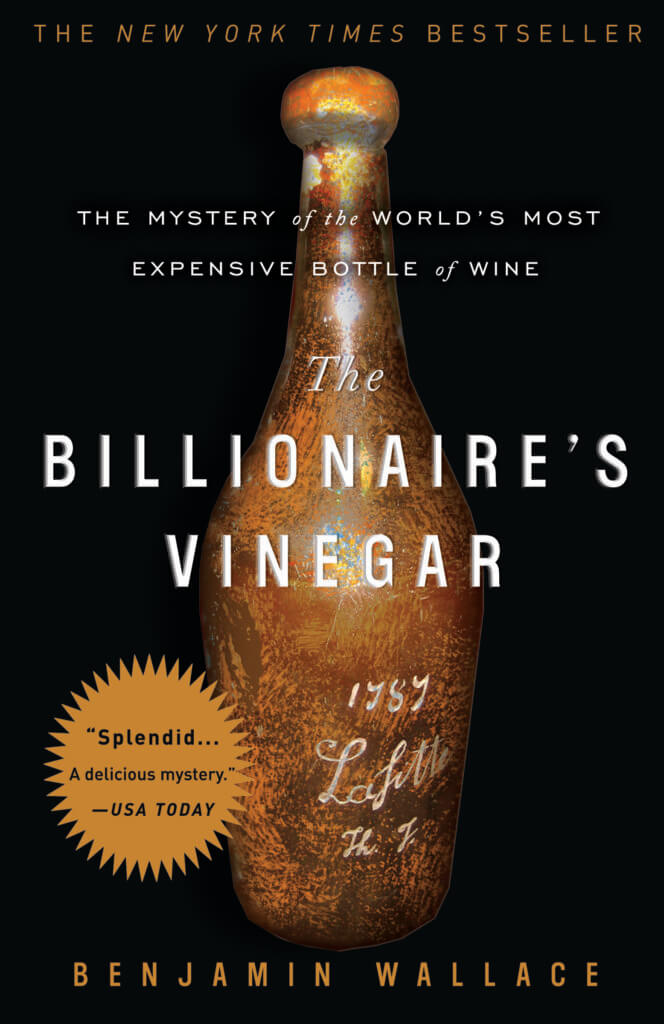

- The Story of The Billionaire’s Vinegar – Part 1

- The Story of The Billionaire’s Vinegar – Part 2

- Blind Tasting Top 2021 Super Tuscans

- Top of the Pops: Classic Fizz Beyond Champagne

- Rock and Rhône

- Our WINES OF THE YEAR (2025)

- Our BOOKS OF THE YEAR (2025)

- Hugh Johnson UNCUT

- McLaren Vale – Boxer to Ballerina

- McLaren Vale – The Grenaissance

Summary

We’re in the middle of, ‘the mystery of the world’s most expensive bottle of wine.’

We’ve seen the auction, met the protagonists, got a vivid taste for the heady wine-boom time of the 1980s and 90s…hell, the cork has even dramatically dropped out already (an appropriate metaphor if ever there was one).

That’s all in Part 1.

Now we get stuck into the heart of our story.

What were the doubts about this magical bottle of wine, and others like it?

Who was this mysterious Hardy Rodenstock character really?

And how on earth might a dead frog, a dentist’s drill, windscreen wipers, an ‘egghead’, and radioactive isotopes crop up in the plot?!

Benjamin Wallace, author of The Billionaire’s Vinegar, is our expert guide, also exploring the fall-out not just from his book (including his publisher being sued) but also the broader ramifications for the key characters and the wine world in general.

We also have some final words from influential wine trade characters featured in the book, with their unflinching take on Hardy Rodenstock and his legacy.

Starring

- Benjamin Wallace, author of The Billionaire’s Vinegar

- Susie & Peter

Subscribe

Sign up to Wine Blast PLUS to support the show, enjoy early access to all episodes and get full archive access as well as occasional subscriber-only content.

Just visit WineBlast.co.uk to sign up – it’s very easy, and we will HUGELY appreciate your support.

It takes a monumental amount of work to make Wine Blast happen. Your support will enable the show to continue and grow – and we have lots of fantastic ideas of things we’d like to develop as part of Wine Blast to maximise the wine fun. The more people who sign up, the more we’ll be able to do.

We currently have an 15% Early Bird discount on initial headline subscription prices – just use the Promo Code magnum25 when you pay. But it’s a limited time offer – so don’t hang around!

Links

- In this episode, Benjamin makes passing reference to research carried out by Lucia ‘Cinder’ Stanton (née Goodwin). You can read it via this link: RESEARCH REPORT: Chateau Lafite 1787, with initials ‘Th. J.’

- You can also read a bit more about Thomas Jefferson’s fascinating relationship with wine in a fascinating piece on Monticello’s website: Thomas Jefferson and wine

- Benjamin Wallace is an excellent writer – do check out his latest book, The Mysterious Mr Nakamoto

- You can find our podcast on all major audio players: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Amazon and beyond. If you’re on a mobile, the button below will redirect you automatically to this episode on an audio platform on your device. (If you’re on a PC or desktop, it will just return you to this page – in which case, get your phone out! Or find one of the above platforms on your browser.)

Get in touch!

We love to hear from you.

You can send us an email. Or find us on social media (links on the footer below).

Or, better still, leave us a voice message via the magic of SpeakPipe:

Transcript

This transcript is AI generated. It’s not perfect.

Peter: Hello, you’re listening to Wine Blast. Welcome to our wine-fuelled world! And you catch us in the middle of a compelling story about the mystery of the world’s most expensive bottle of wine.

Susie: So this is the second and concluding part of our Billionaire’s Vinegar story. In the first part, we met the main protagonists, got a taste for the heady wine boom times, and enjoyed the drama of the 1985 auction in which a bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite engraved with Thomas Jefferson’s initials sold for a record break breaking £105,000, making it the most expensive bottle of wine ever sold at the time…

Peter: Before the cork fell in, making the most expensive bottle of vinegar on the planet. Meanwhile, though, doubts were being raised about the authenticity of this bottle and the trustworthiness of its consigner, wine collector and dealer Hardy Rodenstock. Here’s a taster of what one of the investigations threw up and its ramifications.

Benjamin Wallace: In the basement he found empty old wine bottles, a stack of blank wine labels, all old labels. He found a pile of dirt with a dead frog in it and with mould all over it. Obviously this was Rodenstock’s laboratory where he was creating his old bottles of wine. I think there was a gradual kind of waking up from the slumber of the romance of the wine world where nothing like this could ever happen, would ever happen. The bloom was off the rose, the innocence was lost.

Susie: Benjamin Wallace there, author of the 2008 book The Billionaire’s Vinegar. So the ideal voice to talk us through this fascinating story and its aftermath. But before we dive right back in, there are a couple of things to preface, aren’t there?

Peter: Indeed. so it’s worth bearing in mind the story told by Rodenstock of how he had found this unique cache of 18th century wines. He said that building works in Paris had knocked through a brick wall into a hidden cellar where a number of bottles of wine had been miraculously preserved since French Revolution times in perfect condition, including top Bordeaux like Chateau Lafite and Yquem. the hoard included an unspecified number of bottles engraved with the initials Th.J. which were quickly associated with US founding father Thomas Jefferson. these became known as the Jefferson bottles.

Susie: And just a couple of details relating to Bordeaux. Chateau Petrus is the famous Pomerol estate that commands eye watering prices. Made in tiny quantities and very much a, favourite with collectors. Much the same can be said of Chateau d’Yquem the famously unctuous and long lived sweet wine from Sauternes in Bordeaux, which was owned and run by the Lur Saluces family from 1785 to 1996. And Branne Mouton is the old name for Chateau Mouton Rothschild, these days one of the five Bordeaux first growths. So the top red estates of the Left Bank.

Peter: Monticello was Thomas Jefferson’s residence in Virginia, which more recently has been transformed into a museum, an educational institution run by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

Susie: Finally, we touch on dating wines by measuring radioactive isotopes. This is complicated, but one simple takeaway is that agricultural products like wine retain traces of their environment. Since hydrogen and nuclear bomb testing began in the 1940s and 50s, cesium 137 isotopes have been detectable in the atmosphere and in wine in varying quantities year to year, but not so much in wines before that time. So if you test a very old wine and it has high levels of cesium 137, it’s a fake physics lesson over.

Peter: Thanks for that. Right, so I asked Benjamin to give us an insight into the world of Thomas Jefferson and, his possessions and memorabilia and the place of specific wines within that, particularly the 1787 Lafite.

Benjamin Wallace: One of the things I looked into was if this was a Jefferson bottle, like how might it have ended up in this bricked up cellar? And was there a record of him ordering 1787 Laffite? Jefferson was like what today we might call OCD about record keeping. The leading Jefferson scholar at Monticello, this woman, Cinder Stanton, said, you know, he didn’t have a wastebasket and he was a hero of meticulousness. It was just unbelievable, like his redundant record keeping. Every bottle of wine he’d ever bought, there was a record of, and there was a record of it in like four different places. And so, you know, there, there was quite a paper trail on like what had happened to all of his possessions. But there were also some blank areas of mystery where conceivably a bottle or a case or more than a case could have gone

00:05:00

Benjamin Wallace: missing. I mean, there was, at one point there was a ship that was bringing a bunch of his possessions up the coast of the US that, you know, went down in a storm. There was a fire at some Point, there was a lot of kind of drama with his possessions after his death as well. And so over the years, these things occasionally would pop up, like they’d just be found in weird places or they would come to auction out of nowhere. And so, there was kind of a diaspora of Jefferson’s possessions and there was simultaneously an attempt to gather them up by Monticello, which was establishing itself as this kind of historic repository and museum of Jeffersoniana. And so there was a history of sort of Jefferson object hunting that I was able to follow a little bit in the book. But this 1787 Lafite find was truly spectacular and probably the most spectacular Jefferson find that there had been since his death in 1826, I think, which is.

Peter: Interesting in itself, I suppose. And the Jefferson experts at Monticello did get involved, albeit so slightly obliquely, in this, didn’t they? because obviously this is quite unimportant if you think that you’re selling a 1787, Chateau Lafite that belongs to Thomas Jefferson. Presumably you want to consult the experts. what did the Jefferson experts have to say about this find? Because they weren’t really consulted that much before the sale, were they?

Benjamin Wallace: That’s right. I mean, as I recall, I don’t think that Christie’s did solicit the advice of Monticello and the experts there. But what did happen was the New York Times wrote an article about this forthcoming auction because Christie’s was flogging it, you know, for the pr. And the New York Times called Monticello and asked about this bottle and, you know, can you make sense of sort of how this could have ended up in this bricked up cellar in Paris And Cinder Stanton, this, this. I think maybe at the time she was Cinder Goodwin, but later became Cinder Stanton. She was the expert. She was so diligent, she was deeply familiar with Jefferson’s records. And so she quickly tried to do a study on like, you know, how did this correspond to the records? And I don’t think she finished her research before the auction, but maybe like a week later. But she did do enough prior to the auction to tell the New York Times that, you know, there was some reason for scepticism about this bottle just because of the specific vintage, that it was, and the specific chateau and the specific combination of vintage and chateau and what Jefferson’s record said and the absence of any mention in his records of lost wine in Paris, during the French Revolution.

Peter: And also there was something about the actual nature of the, initials that had been engraved, weren’t there?

Benjamin Wallace: yeah, I mean it didn’t. The way they were engraved in the bottle was th. if I’m remembering correctly, it was TH was Th.J. But I forget whether there were periods after the TH and after the J. But in any case, they did not correspond to the known ways that Jefferson had ever signed his name or even engraved a bottle. Because there were some bottles that he had made reference to having like marked with a diamond, in some way to indicate that they were his. But it was not nearly as camera ready as like his own initials, let’s put it that way.

Peter: Camera ready. and as you said, this man was a meticulous record keeper. But there were no specific records of these purchases ever having been made?

Benjamin Wallace: No, I mean there were close ones. Like maybe there was a 1784 of, maybe Lafite, but of something of first growth. And maybe there was even a 1787, but it was not of a first growth. And there was no combination of Lafite in 1787 in his records.

Peter: And what was the reaction from Broadbent and Rodenstock to this, Jefferson expert weighing in?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, they were very dismissive and sort of treated her as a clueless egghead who knew nothing about wine. Not that that was really relevant because she wasn’t opining, on the wine, but merely on whether or not Jefferson’s record showed him to have owned a bottle like this. But so, yeah, they kind of glossed over it.

Peter: and were these reservations shared by the wine world or not? Was everyone sort of behind it and then gung ho fever?

Benjamin Wallace: Pretty gung ho. I mean, you know, the wine world was, and especially the high end wine world was a pretty insular thing that wasn’t of interest to a great many people outside of it. And inside that world, you know, it was very much a culture of marketing and salesmanship and storytelling and forensic scepticism just was not a part of the vocabulary of that world. I mean it just, it wasn’t, it was very much against the spirit of the world. It felt very contrary to the spirit of wine that, you know, and I think like the culture of the wine world certainly at that time was an important part of this whole story.

Peter: But there were reservations, at least starting to grow in some circles, weren’t there? And doubts about Hardy Rodenstock and his wines. Can you tell us a little bit about Herr Petrus and his case, his legal case against Hardy Rodenstock?

Benjamin Wallace: Sure. So Herr

00:10:00

Benjamin Wallace: Petrus was a guy named Hans Peter Freirerichs, who had made his money in, I mean, like, a number of these guys. Many of them had made their money in sort of very boring ways. And Hans Peter Ferrix, I think, was selling, like, windshield wipers in supermarkets and maybe like, PVC gloves that were like anti AIDS protectant gloves that at the time had been mandated by German law that every car must have, and just like, weird things like that. But he’d made a lot of money and he spent a lot of it on wine. And he became the Petrus guy, and he, at a certain point, became less interested in wine. And he decided he wanted to sell his cellar. And he asked Sotheby’s. Sotheby’s to handle the sale. And I don’t recall whether it was because he sort of knew that Christie’s was aligned with Rodenstock. But in any case, Sotheby’s auctioneer David Molyneux Berry came to his home to check out the cellar. You know, to sort of start figuring out how to put a catalogue together. And Molyneux Berry became convinced that a lot of the wines in the cellar were fake. You know, the labels didn’t quite match, like, you know, the labels as he knew them, things like that. There was a guy with him who was taking notes on the wines and. Or who had the cellar book with him. And Molyneux Berry would go around, and when he saw a bottle that was. That he thought was fake, he’d say whatever the bin number, the tag number on it, and the guy holding the cellar book would read off the source that was recorded in the cellar book for each wine. And so Molyneux Berry you know, would say, Margaux you know, 1812, whatever. And the guy would be like, source Rodenstock. And it went on and on like that. Like every time Molyneux Berry came upon a wine that was fake, he would. He would read off the number and the guy would look and it would be Rodenstock. So needless to say, that made them extremely suspicious, of rock. So Sotheby’s refused to take the consignment. I think it was like the second time in or third time in David Molyneu Berry’s career that they had not taken a consignment. I mean, that’s not what. Auction. Auctioneers don’t not take consignments. That’s, you know, so Freirichs was annoyed by this. And, there was actually one other reason why Sotheby is refused, which was that when Rodenstock caught wind of the fact that Freirichs was trying to sell, his wine. He said, oh, no, no, no, no, no. Like, I sold you those bottles at a friendship price because of our relationship. And like, it was always understood you would not be allowed to resell them. So Freck’s became very suspicious of that. Like, why would Rodenstock care if other people have an opportunity to inspect this bottle, Et cetera, et cetera. So eventually Freirichs sued Rodenstock. He had one of these bottles laboratory tested. The laboratory determined that the bottle must be from the nuclear age, because in the nuclear age, like every year, there are certain levels of different radioisotopes that work their way into any agricultural product that is harvested in that particular year. And so if something was made, if a wine came from what came from grapes after 1962 or whatever it was, then it would say, you know, this wine is from 1963, this wine’s from 1967. Certainly not. So his wine was clearly not from the 18th century. This began a kind of war of words in the wine press and in the German tabloids between Rodenstock and Freirichs And eventually Rodenstock, I mean, Rodenstock said, you know, came forth with photographs showing before and after that, he said, showed that Freirichs had tampered with the bottle to make him look bad. Like he had one where he’s like, the bottle, as I sold it to him, had a high fill. The bottle Freirichs is showing now has a low fill. so clearly he tampered with the bottle. So Rodenstock decided to have a counter test done. And he sent off another bottle to this laboratory in Switzerland that I think had been the same lab that had authenticated the Shroud of Turin. And they did their own chemical and sort of radioisotope dating. And this one seemed to vindicate Rodenstock and, you know, said it was from. Predated the nuclear age. Although even with those tests, there was like a ridiculously large margin of error, like plus or minus 200 years. So, I mean, it was. It certainly didn’t like pinpoint it to 1787 or whatever the vintage was. And the way that the case sort of landed in the wine world was that it was kind of a. He said, he said it wasn’t clear what the truth was. The most recent test had shown that Rodenstock was in fact, in the right. I think Freirichs was seen as a little bit of an unserious person. So maybe people were willing to give a little more credibility to Rodenstock. But something that was overlooked by the wine scene was that a Munich court had actually found Frerex’s, first bottle to contain, knowingly, I think, adulterated wine. So it really

00:15:00

Benjamin Wallace: had found in favour of Freirichs in a fairly decisive way. But it just didn’t get reported in the wine press that, I don’t recall exactly why, but that particular detail was not reported. And so it was it. There just remained this kind of cloud where people who were inclined to not trust Rodenstock could not trust him. But if you basically wanted to go on being invited to his, his tastings and think the best of him, you could do that with good conscience.

Peter: And that Munich judgement was in 1992, wasn’t it? I think so, yeah. And Rodenstock clearly carried on doing his own merry thing, for a fair while after that. What was, Rodenstock’s general response to these sort of, you know, obviously he’d been taken to court, he’d been sued to these doubts being aired and these people, you know, suing him.

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, you know, he would insult them, he would sometimes threaten litigation. I mean, one of the features of this controversy was that often any wine magazine that reported on, let’s say, Freirex’s case or someone else’s scepticism about Rodenstock bottles would suddenly be inundated with correspondence, often from people no one had ever heard of. Like, well, some of the letters were from a guy named Gisbert Gorke. There was another one, another bunch from a guy named Hubert Meyer. But they all, kind of sounded the same and they all basically attacked Rodenstock’s critics as idiots and praised Rodenstock.

Peter: And what do we think about the identity of these various different people?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, you know, spoiler alert. I think they were all Rodenstock.

Peter: But, you know, despite all these doubts and adverse court judgments, did it seem at one stage as if the mystery of the billionaire’s vinegar and its finder was simply sort of fading into obscurity and there was nothing more going to come out about it?

Benjamin Wallace: Very much so. I mean, I think there were like little isolated groups that became disenchanted with Rodenstock? Right. So you had, like, the German group had become disenchanted with him that included Herr Petrus. there was a California group that had become very sceptical of his bottles, and had in some tiny obscure newsletter, they had done their own kind of, you Know, quite microscopic, analyses of the corks and labels on his bottles and things like that. But in general, yeah, Rodenstock was going about his business. He still was hosting these tastings. He was still getting, well known people to attend them. I mean, a couple of the chateau had become very sceptical of him. Like he had a falling out with Alexandre de Lur Saluces from Yquem. Among other reasons being that he told Lur Salusse, that the way he was making ikem was wrong. Lur Saluces was quite offended. And so, yeah, it kind of just had disappeared. It really had gone away.

Susie: The calm before the storm. Interesting, isn’t it, about not only the Jefferson experts being somewhat sidelined, but also that 1992 Munich court decision that went largely under the radar, as Ben says. It certainly does seem like scepticism wasn’t part of the vocabulary of the wine world at that time.

Peter: It’s very well put, isn’t it? I mean, sometimes a story is just so good you almost feel compelled to believe it, you know, even when the evidence starts stacking up to the contrary. I guess it’s just the way our brains work, isn’t it, really? and, and in the concluding part. Now we’ll get on to comeuppance and the aftermath of all of this.

Peter: To recap so far, Hardy Rodenstock had once been feted as a golden boy among, wine collectors for his uncanny ability to find and sell ultra rare old vintages of top wine and also host lavish mega tastings. But increasingly significant doubts were being raised about the authenticity of these wines into the 1990s and turn of the millennium. Nevertheless, there came a point when the trail seemed to have gone cold.

Susie: That was until one man decided to take matters into his own hands. I’ll let Benjamin Wallace, author of the Billionaire’s Vinegar, take over at this point.

Benjamin Wallace: in 2005, I began working full time on this book and one of the first things I did was go spend a week at Monticello, where they have the library, they have all the Jefferson papers, et cetera. And my first day at the library there, the librarian said, so. Strange how there’s all this interest in this suddenly, there was just someone here last month inquiring about exactly the same thing. And I, you know, had my journalistic freak out of, oh, no, you know, I’m getting scooped by some other journalist who’s also onto the story. And I waited too long because I had been kind of incubating this book. For like five years before that. But they said, oh, no, it was an investigator for, a gentleman named Bill Koch who was there at the library. So this was actually the first time I became aware

00:20:00

Benjamin Wallace: of Bill Koch And Bill Koch is a billionaire and a member of a family of billionaires that made their money in the coke and petroleum business. Very colourful guy. He had had a very dramatic, litigious falling out with his brothers, including his twin brother. At one point he had subpoenaed his own mother into court after she had a stroke. I mean, it was really like quite, quite a thing. But Koch was, less involved in the main family business and spent a lot of his time and his money collecting and he collected a lot of things. he had won the America’s cup sailing race in 1992 just by throwing money at sort of scientifically developing a better hull. he collected the revolver that killed Jesse James. And he had an enormous wine collection of 30 or 35,000 bottles which he had developed his own. He had a PhD in chemical engineering and he had developed his own filtration system to decant, you know, his older bottles. So the Boston Museum of Fine Arts had asked Koch if he would, you know, do an exhibit of all of his collections. They, I think they thought it would be kind of popular with the public. I mean, some of the snobbier people thought it was quite philistine, that they were just letting some rich guys show off his toys. But it was gonna be probably a crowd pleasing exhibit. So one of the things that Koch wanted to have in this exhibition was his four Jefferson bottles. Because after that initial auction, Rodenstock had continued to sell other Jefferson bottles. Eventually, Marvin Shanken, the underbidder in the 1985 auction, the wine Spectator creator, he finally got his Jefferson bottle at a different auction. And far Farr vintners, the private merchants, had sold Coke four Jefferson bottles, all engraved with the initials. I think there was at least a Laffitte, maybe there was a Branne Mouton, which was the pre, the earlier name of Mouton Rothschild. So in the course of preparing this exhibition for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the museum wanted documented provenance for every object that was going to be in the show. And Koch or his curator realised they didn’t really have it for these bottles. And so I think they went to far. Maybe they had the receipt from the sale, but I think Farr just referred them to Rodenstock. Koch’s people contacted Rodenstock, who was not forthcoming with provenance. So Koch became suspicious of the origin of these bottles. And he was someone with really unlimited resources, effectively. And so he initially delegated a full time investigator, a former FBI agent named Jim Elroy, to really dig in and see if he could determine the origin of these bottles. And eventually other investigators became involved. It became a, you know, world spanning investigation with multiple investigators, with investigators, a bunch of lab tests. And he spent millions of dollars on this investigation, much more than he had spent on the Jefferson bottles, which I think maybe he spent 500,000 for all four. And that’s really what reawakened the, the mystery of the Jefferson bottles.

Peter: And what did he and his crack team of investigators find out about Hardy Rodenstock? This man known as Hardy Rodenstock.

Benjamin Wallace: So, I mean, they found out a bunch of things. I mean, one thing was Rodenstock had always been a little bit of a, cypher when it came to anything really about him beyond his wine. Like even the people who knew him really well and best through the wine world, people like, Broadbent, people like some of the other German collectors, didn’t really know anything about his family history. Rodenstock had always kind of told a story about how he’d been an accomplished academic, impeccably credentialed academic at one point before he got interested in wine. People also knew him for having been the manager of a bunch of German pop acts in a genre known as Schlager, which was sort of slightly cheesy, basically pop. but he’d been quite successful as a manager in that. But then he’d gotten into wine as a hobby. But no one knew anything about really his personal history. So Koch’s investigators found, among other things, that he’d come from a humbler background than he had claimed, that he, I think, had been born maybe in Poland and then ended up in a refugee camp. This was during, you know, during World War II or right after World War II. And his name was not Hardy Rodenstock. I mean, Rodenstock had always either said or implied that he was a member of this like, very wealthy German family, the Rodenstocks, that had made their money in like the optics business. He had no connection to them. Rodenstock was a name he had taken on later. His real name was Meinhard Gorke. And in fact it turned out that Gisbert Goerke, the guy, one of the names of people who’d been sending these letters to the magazines was his brother, who Koch’s investigator gratuitously described as a very small Sized man. and Rodenstock had two kids, I think, Oliver and

00:25:00

Benjamin Wallace: Torsten Gorka. But no one, no one in his circles really knew this. I mean, there was one guy, his sort of pet sommelier, sidekick, who at some point had accidentally found out because he was in a restaurant and the waiter had said, oh, I read about you in the paper. I think, you know, my father is a, you know, Meinhardt Gorke and he’s like, you know, Hardy Rodenstock. So that’s how he found out. But no one else, no one else knew this. so he really was somebody who had kind of reinvented or invented himself.

Peter: And then Koch’s investigators also discovered, an intriguing case about Hardy Rodenstocks or Meinhard Gorka’s former landlord. Can you tell us about that, too?

Benjamin Wallace: One of Hardy Rodenstock’s homes was a twin, you know, with another house in Munich. and the person who lived in the other half of the building in the other twin, was the landlord. They owned the property, and at some point they ended up in a landlord tenant dispute. for various reasons. It was mould in the attic, I think. And at some point, you know, Rodenstock refused to move out, and was demanding increasingly high amounts of money to move out. And then at some point, because of the mould, he temporarily did move out, but he did not relinquish his tenant rights. And I think the landlord who lived in the other half of the house got it in his head that if he could prove that Rodenstock was actually working out of this other half of the building, he could use that to get him out of there because he was declaring Munich as his residence or something. And so he went into the, into the Rodenstock half of the house when Rodenstock wasn’t there. And in the basement, he found empty old wine bottles, a stack of blank wine labels, all old labels. He found a pile of dirt with a dead frog in it and with mould all over it. And it became very clear to him. Oh, and also, I mean, he’d been hearing for years, he’d been hearing this, like, hammering, which he knew Rodenstock was in the wine business, but it sounded like he was hammering wine crates together, wine cases. And he couldn’t for the life of him figure out why Rodenstock would be doing this grunt work when he is this kind of like flashy high end wine dealer. And so it became the picture gelled for Andreas Klein, this landlord, and the other half of the house that Rodenstock was obviously. And he’d read about the lawsuits, obviously. This was Rodenstock’s laboratory where he was creating his old bottles of wine.

Peter: Didn’t they discover something about he’d owned a sort of perfumes business, is that right?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, that was a sort of tantalising, you know, bit of trivia that Koch’s investigators found that Rodenstock did own a business that, you know, made perfumes or essences that were used in the manufacture of perfumes. And, you know, that was intriguing, but they never really learned any more about it, so it didn’t go anywhere. But it did occur to them that, you know, if he has sort of these professional chemical mixologists on his payroll, that would be handy for someone who is concocting, you know, very specific tastes of wine.

Peter: And Koch’s team also homed in on one particular detail about the engraving on the Jefferson bottles, didn’t they? Which led to a quite remarkable conclusion. Can you tell us about that?

Benjamin Wallace: you know, in the time of Thomas Jefferson and The, you know, 1780s, the way that engraving was done was using a method called copper wheel engraving, where the person would, I think, sit at a. They’d use a pedal, sort of a pneumatic pedal to turn a wheel made of copper that would be used to make these engravings. And so Koch’s investigator took his bottles up to the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York, you know, where there’s some very skilled glass experts. And they examined the, engravings and said they could not have. And they did. They took, like, another bottle and tried to duplicate the engravings on the Jefferson bottles using copper wheel engraving, and they could not. And they ultimately determined that the only way to have made the engraving was using a modern power tool such as a dentist’s drill.

Peter: A dentist’s drill?

Benjamin Wallace: Yeah.

Peter: How did the Koch case end up?

Benjamin Wallace: So Koch sued Rodenstock in New York. I don’t remember why he thought he had jurisdiction there. Maybe because he had sold a bunch of other bottles that Koch had bought through New York merchants. And, basically, Rodenstock initially participated, like, he responded to the filings. He hired a New York lawyer. But eventually Rodenstock just stopped responding to filings. He, you know, got rid of his lawyer and that was kind of the end of it. And so Koch won what’s called a default judgement, where the court finds in your favour. and he was awarded damages. But then it’s sort of an academic question because, like, could he collect on those damages? And I don’t think he ever could because Rodenstock, like then moved to Austria and like, I mean, you know, he sort of sheltered himself within European tax laws or European privacy laws and jurisdictional, you know, boundaries. But he did end up having a lot of his own tax problems in those countries because I think he was living in Austria, but claiming Munich was his residence. And so

00:30:00

Benjamin Wallace: independent of all of this wine stuff, he had a bunch of tax problems he had to deal with over there. but, you know, Koch never really got any further justice against Rodenstock.

Peter: And what was the reaction in the wider wine world to all of this?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, I think there was a gradual dawning, a gradual kind of waking up from the slumber of the romance of the wine world where nothing like this could ever happen, would ever happen. You shouldn’t even ask questions like that, et cetera. I think the bloom was off the rose, the innocence was lost. You know, it took a while. I mean, Broadbent continued to insist that the bottles were authentic. he never conceded any ground there. I mean, he always maintained that they were authentic. I think he did believe that, but I think it was sort of a artefact of just like psychological self delusion. Like, I think he wanted to believe that. He needed to believe that. He’d really staked his reputation in a lot of ways on that. I mean, his big book of sort of the Taste of Wine historically, all of the rarest ones in there that really distinguished it as something no one else would ever be able to replicate were Rodenstock sourced bottles. The 1985 sale was a huge deal for him. So he did not necessarily have an awakening, but I think most other people did.

Peter: and ultimately the case was never definitively proven against Rodenstock.

Benjamin Wallace: There was never a criminal finding against Rodenstock. There was. I mean, even Koch’s case was not a criminal case. It was a civil case, you know, seeking money, damages. And a, default judgement is not the same as a finding of culpability or guilt.

Peter: And do we still think that, you know, sort of almost 20 years further down the line, is that still the. Obviously there hasn’t been a criminal finding against him, but what’s the general, body of opinion nowadays, do you think?

Benjamin Wallace: I’d be surprised if there’s anyone in the world alive today who thinks Rodenstock was on the up and up.

Peter: And, just from a personal point of view, your book the Billionaire’s Vinegar was published in 2008. Can you remember what the reaction was at that time to the book being Published.

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, it was pretty good. I mean, I would say when I was working on the book I encountered a certain amount of resistance and reticence because that was still before, like the bloom was not yet off the rose. And so I was fighting a little bit against, against that culture of not really scrutinising everything. But you know, by the time that my book came out, like Koch’s lawsuits had already been well publicised, so it wasn’t like brand new news. And so my book was seen as kind of just documenting a thing that had happened in the world. I mean, Rodenstock certainly didn’t like it. He, I think he told a Bloomberg reporter that it was a, what he called a Markenbuch, which I’m told means fairy tale and in German. And, Bill Koch actually didn’t like it, even though I think I’d give him his due as like in many ways the hero of the story. But, you know, I portrayed some of his peccadillos and I don’t think he loved that. And Michael Broadbent was interesting because after I sent him the book, he left me a voicemail or at the time it was actually, I think on a physical answering machine. This was not, you know, 2008 and, saying, you know, I was worried I wasn’t gonna. I have to say I was, I was kind of, I was quite nervous about this book and I was worried, you know, about what it might say. But I, you know, I really like it. Like it’s a, you know, it’s a, like it’s really, you know, well written. And I, da, da da da da. I was like, oh, that’s great, that’s nice. that did not last. That feeling and sentiment did not last. You know, I forget whether it was one year later, two years later, but, but Broadbent, sued my publisher for, I imagine, defamation. It must have been defamation in the uk, as your listeners may or may not know. You know, UK libel law is different from the law in the us. In the us, the burden is on the, person who claims they’ve been liable to prove that they’ve, you know, to prove that what was said was false. And in the uk, at least at that time, the burden was on the journalist to prove that what they wrote was true. So eventually, I mean, the publisher defended the case for a while, eventually having spent more money than they wanted to spend and not basically made a business decision to settle with Broadbent, they apologised in open court to him and they agreed to no longer sell the book in the uk. Simultaneously, they issued a statement strongly supporting me. They didn’t change a word of the book and they continued to distribute it everywhere else unchanged.

Peter: Well, how did you react to that, personally?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, I don’t love that they made the business. I understand the business decision they made. I don’t love it. I don’t love that they apologised because that was just a sort of insincere litigation posture made for economic reasons. But I understand it as a corporation.

00:35:00

Benjamin Wallace: you know, one thing I’ve always said and felt and did at the time is that I don’t think I did libel Michael Broadbent. I mean, I don’t think I portray him as a malefactor or as anyone who did anything sort of intentionally improper. I do think he was a salesman. He was a very competitive salesman. extremely competitive with Sotheby’s. This was a huge coup for him and I think he kind of had the salesman’s blinders on. And I just think this was a blind spot for him. and he became so invested in that relationship and what it had meant for his reputation that he just could not. He couldn’t see it clearly. and so I. You know, I don’t. I wish he didn’t. Hadn’t ended up feeling the way he did about the book. I always felt good feelings toward him and kind of thought he was, in many ways a kind of a great man, but it was what it was.

Peter: And what became of Hardy Rodenstock?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, he kind of faded into the gloaming. I mean, he apparently did continue to hold some, like, private commercial tastings, but he basically kind of faded away. I think he spent a lot of time at Kitzbuhl, where he was, you know, married for a while to a former German actress. And then in 2018, he died.

Peter: And, nothing more has, happened on that front since.

Benjamin Wallace: Not with Rodenstock. I mean, it would have been. It would have been satisfying if, like, some member of his family had come forward with some kind of either, you know, deathbed confession from their dad or just their own accusation or evidence. That would have been kind of narratively pleasing, but it did not happen.

Peter: So 40 years on, from that famous auction sale in 1985 of the 1787 Jefferson Lafite, that marks the dramatic start to your book. How do you think that the world has changed since then and the world of fine wine has changed?

Benjamin Wallace: I mean, I do think there’s been a broader reckoning in the wine world that, like, fraud is a real thing. It happens at the high end. I think some of the chateau have put in place better protections like RFID chips in bottles and things like that that make them more traceable. But the other thing is, like, this really was an artefact of a moment in time because Broadbent found all the old wine, he got all the old wine, he sold all the old wine. A lot of that old wine was drunk. There’s less and less of that old wine. And even of the old wine that has survived, it’s now like so old that it’s probably not drinkable anymore. So if it ever was. And so I do think in that sense that, you know, you’re never going to have another scene with like 125-year-old bottles being found because that’s done. The supply was depleted.

Peter: Benjamin, thank you very much indeed.

Benjamin Wallace: Peter, thanks so much for having me.

Susie: So we’re talking a dentist’s drill, a dead frog, a change of name and a secret family.

Peter: Don’t be getting any ideas. really though, that’s not all. That’s not all, you know. After Ben’s book was published, German magazine, Stern tracked down a printing company in Germany where several employees testified that Rodenstock had frequently commissioned the firm to reprint old wine labels. More than that, Stern got hold of labels of supposedly Mouton 1900 that came from rodent stock, and chemical analysis showed that the label was backed by modern synthetic glue, not invented until years later.

Susie: Despite all of this, though, there was never a criminal judgement against Hardy Rodenstock, was there?

Peter: No. Which is. Which is worth, you know.

Susie: Yeah. No satisfying conclusion to the story other than the wine world, I guess, being forced to take, start taking the issue seriously, even if not eradicating the problem. Because frauds are still a big issue, as we discussed in our Fake Wine episode.

Peter: We did, we did belong with Homer Simpson, but that’s another. That’s another matter. and of course that’s a shame because it just erodes trust. And, you know, a lot of wine is about trust. But the wine world really does need to become more transparent, from producers to middlemen to merchants to auctioneers. Which is what Maureen Downey was saying, in that episode, wasn’t it? yeah, and that does seem to be happening, you know, but just quite slowly. Is that a fair way of.

Susie: Yeah, yeah. And in the meantime, we got some other input, didn’t we, from people like Serena Sutcliffe and Jancis Robinson too, didn’t we?

Peter: We did we did. both of whom figure in the Billionaires Vinegar story. Jancis in her role as journalist and Serena as head of wine for auctioneer Sotheby’s. Jantis called Roden Stock spooky when we spoke and said he clearly derived pleasure from seeing his friends cheated. Serena said, and I quote, hardy Rodenstock was a disgrace and so were the people who sold his wines. an insult to those of us who love wine and wish always to protect its integrity.

Susie: Certainly not mincing words. And perhaps an appropriate note to end on by way of closing summary. While the mystery of the world’s most expensive bottle of wine may

00:40:00

Susie: not have been conclusively resolved either way, it does now seem likely that the story was just too good to be true. The naive romanticism of the wine world has been challenged. You know the trade. Tasked with adapting and evolving. Meantime, the story lives on as a cautionary but entertaining tale that all wine lovers would be wise to heed.

Peter: Thanks to Benjamin Wallace, the Billionaires Vinegar really is an excellent read. You can also get Ben’s latest book, the mysterious Mr. Nakamoto, the 15 year quest to Unmask the Secret Genius behind Crypto. in all good bookstores now. Finally, thanks to you for listening. Until next time, cheers!

00:41:11