- Season 7 Trailer

- The Jancis Robinson EXCLUSIVE Part 1

- The Jancis Robinson EXCLUSIVE Part 2

- Chile Wines of the Year 2025

- SAN LEONARDO – The insider’s Guide

- The Story of The Billionaire’s Vinegar – Part 1

- The Story of The Billionaire’s Vinegar – Part 2

- Blind Tasting Top 2021 Super Tuscans

- Top of the Pops: Classic Fizz Beyond Champagne

- Rock and Rhône

- Our WINES OF THE YEAR (2025)

- Our BOOKS OF THE YEAR (2025)

- Hugh Johnson UNCUT

- McLaren Vale – Boxer to Ballerina

- McLaren Vale – The Grenaissance

- Peter Fraser – A Tribute

- New Zealand Wines of the Year 2026

- Sam Neill UNCUT

- Giveaway EXTRAVAGANZA + Game-changer Coravin

- Greg Lambrecht UNCUT

Summary

So what do a boxer, a ballerina and a burlesque dancer have in common?

You’re gonna have to listen to find out…

We’re very excited to be bringing you this mini-series on McLaren Vale, the historic South Australian wine region that’s gone from identity crisis to full-on wine renaissance in just a few decades.

It’s a fascinating story, involving ancient vines, determined winemakers and a healthy appetite for reinvention.

Joining us to bring McLaren Vale to life are Chester Osborn, David Gleave MW, Drew Noon MW, Elena Brooks, Giles Cooke MW, Mary Hamilton, Matthew Deller MW, Andrew ‘Ox’ Hardy, Richard Leask, Stephen Pannell and Toby Bekkers.

Thanks to the McLaren Vale Wine Region for sponsoring this mini-series, which is dedicated to the memory of Peter Fraser.

Don’t miss the next installment!

Starring

- Chester Osborn, d’Arenberg

- David Gleave MW, Willunga 100

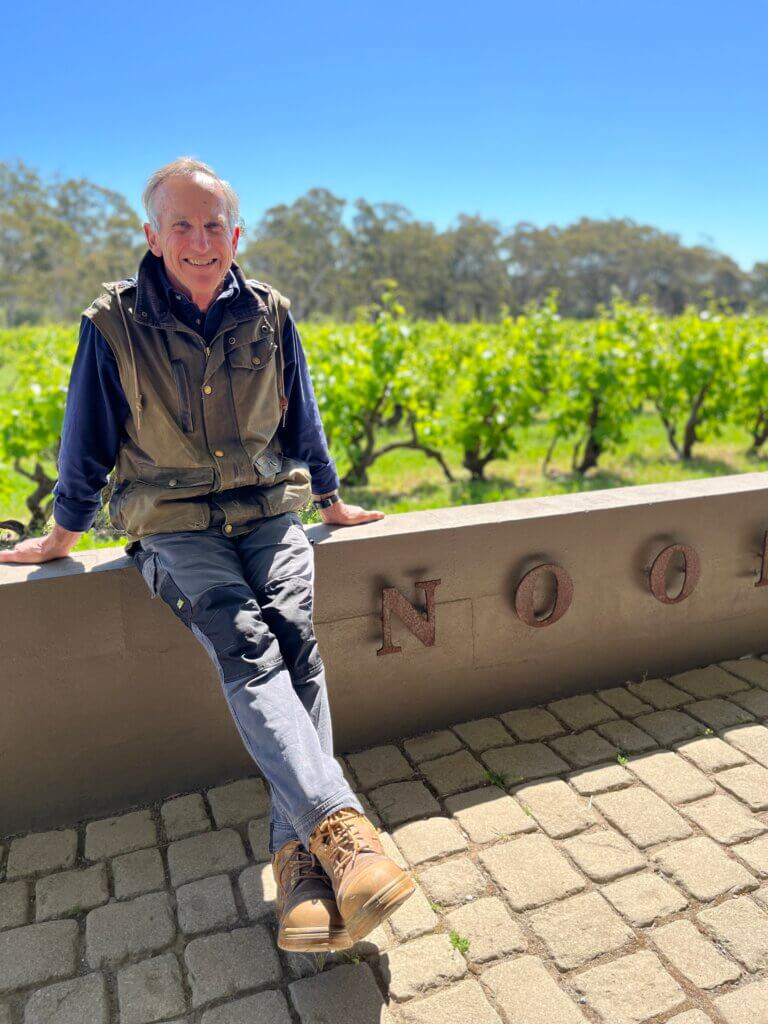

- Drew Noon MW, Noon Winery

- Elena Brooks, Dandelion Vineyards

- Giles Cooke MW, Thistledown Wine Company

- Mary Hamilton, Hugh Hamilton Wines

- Matthew Deller MW, Wirra Wirra

- Andrew ‘Ox’ Hardy, Ox Hardy Wines

- Richard Leask, Hither & Yon

- Stephen Pannell, SC Pannell

- Toby Bekkers, Bekkers Wine

Subscribe!

Sign up to Wine Blast PLUS to support the show, enjoy early access to all episodes and get full archive access as well as subscriber-only bonus content. There are subscriber benefits coming soon, too.

Just visit WineBlast.co.uk to sign up – it’s very easy, and we will HUGELY appreciate your support.

It takes a monumental amount of work to make Wine Blast happen. Your support will enable the show to continue and grow – and we have lots of fantastic ideas of things we’d like to develop as part of Wine Blast to maximise the wine fun. The more people who sign up, the more we’ll be able to do.

Links

- Use this link if you’re keen to enter our Wine Blast One Million Giveaway

- As promised, here’s a link to the McLaren Vale Old Vine Register

- And here’s a link if you’d just like to explore a bit more about McLaren Vale

- Sincere thanks to Erin Leggat and Shaughn Jenkins for their help making this mini-series happen

- You can find our podcast on all major audio players: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Amazon and beyond. If you’re on a mobile, the button below will redirect you automatically to this episode on an audio platform on your device. (If you’re on a PC or desktop, it will just return you to this page – in which case, get your phone out! Or find one of the above platforms on your browser.)

Maps

Images

Video

If you want to get a bit of a feel for what that helicopter ride was like..!

Get in Touch!

We love to hear from you.

You can send us an email. Or find us on social media (links on the footer below).

Or, better still, leave us a voice message via the magic of SpeakPipe:

Transcript

This transcript was AI generated. It’s not perfect.

Peter: Hello and welcome to Wine Blast. Welcome, in fact, to The Vale – the McLaren Vale wine region in Australia. The intriguing subject of this mini series we are very excited to be bringing you!

Susie: But let’s be honest, this doesn’t particularly sound like a wine landscape…

Peter: It’s, a fair point. It’s a fair point. These are, in fact, the bells of St Peter’s Cathedral in Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia, which constitutes the northern border of McLaren Vale. In fact, you could say McLaren Vale’s origins lie under the Adelaide tarmac, because that’s where the first pioneering vines in South Australia were planted. And it’s the start of a fascinating story…

Susie: It is indeed a great story, and one we’ll be telling over the course of the next few episodes. I’ve got a feeling we might need to revisit the significance of the bells and those first vines in a moment, but in the meantime, here’s a taster of what’s coming up:

Mary Hamilton: If you can’t make good wine here, I think you should go and get a different job.

Chester Osborn: We’re a long time six foot under. You know, there’s a lot of life to live out there.

Elena Brooks: The wines are of, such a bigh quality and they’re so interesting. They capture the region, they capture the generation, but they’re not pretentious. It’s quiet luxury.

Richard Leask: Now we’re just embracing a bit of chaos and it’s terrifying and exciting and rewarding all in one.

Peter: Terrifying and exciting and rewarding all in one. Wasn’t there a review of Wine Blast that said something similar?!

Susie: Terrifying, terrifying quantities of wine!!

Peter: Maybe I’ve made that up. Anyway, respectively there we heard from Mary Hamilton, Chester Osborn, Elena Brooks and Richard Leask. And we’ve got many more similarly brilliant guests who will be bringing McLaren Vale to life over the course of the next couple of programmes.

Susie: We’ve also got things like helicopters, thunderstorms, flying fox bats and, of course, fine wine to help paint the picture of what is surely one of the most dynamic wine regions on the planet, reinventing itself before our very eyes with absorbing and delicious results.

Peter: So we should start by thanking the McLaren Vale wine region for sponsoring this mini series and enabling me to travel around and meet the key people and really get under the skin of this intriguing place. Which, to be really honest, wasn’t necessarily one of our favourite wine regions back in the day, was it?

Susie: Well, if we’re talking a while ago. No, no. I think when we were doing our. Our Master of Wine studies, our pretty simplistic rule of thumb, for McLaren Vale was generous, hearty Shiraz or Cabernet perhaps slightly softer, suppler, glossier, bit more mocha and warm earth than its South Australian near neighbour, the Barossa. I remember one Master of Wine described this difference as like, Barossa being the bass and McLaren Vale the treble. and I quite like that, but still quite rich, heavy hitting Australian reds. That, perhaps weren’t quite our cup of tea.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. More recently though, we sort of picked up on exciting things happening there.

Susie: Yeah, yeah. Particularly when it came to new wave Grenache. This is something we touched on back in our Going Gaga for Garnacha episode in season five. And our main focus then was on Spain, but we did touch on Australia. And also I co hosted a masterclass specifically looking at Australian Grenache versus the rest of the world. And suddenly we were tasting quite a bit of this stuff, particularly from McLaren Vale. And our curiosity was well and truly piqued, wasn’t it?

Peter: It was, it was. So when McLaren Vale got in touch, you know, we leapt at the chance to find out more because, you know, this is definitely one of the more intriguing trends on planet wine right now. And I headed out, thanks to you, very graciously letting me go.

Susie: M, you got the golden ticket.

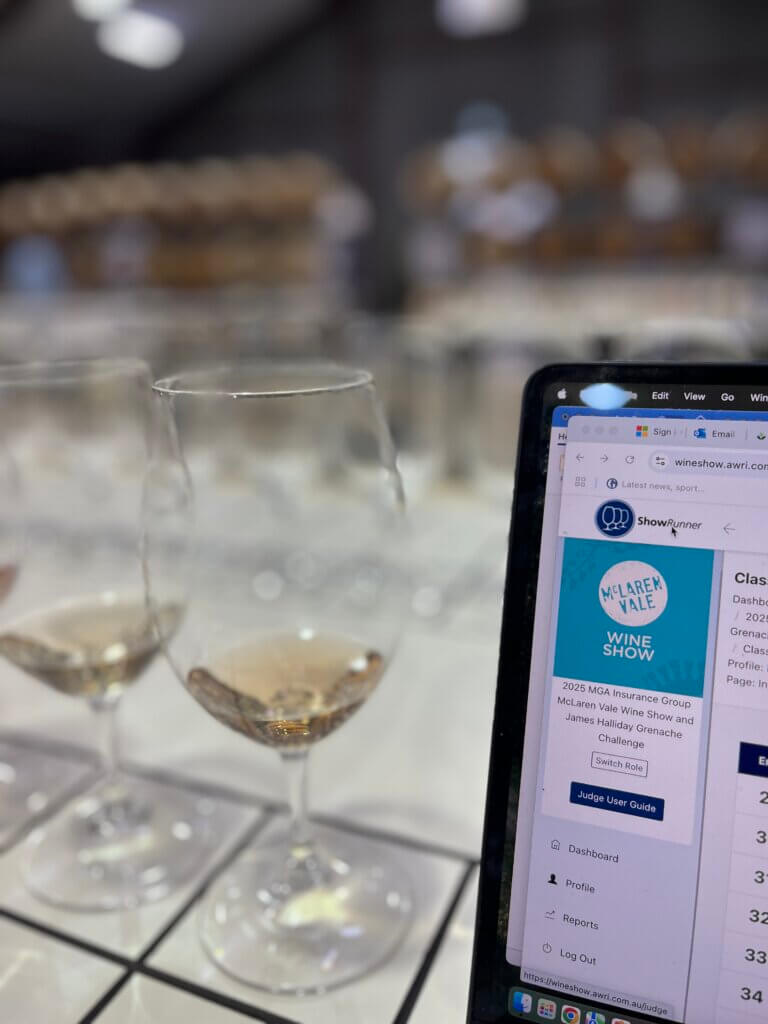

Peter: Yeah. I headed out not only to talk to winemakers, but also to judge in the McLaren Vale Wine Show, you know, where I tasted hundreds of wine to kind of crash course in what the region has to offer today.

Susie: Talking of crashes, you were treated to a novel way to get a feel for the region as well, weren’t you?

Peter: Yeah, thankfully, crashes weren’t involved. Just to clarify, despite my nightmares maybe, yet no sooner had my feet touched the ground in McLaren Vale than I was ushered into a different kind of transport and I was hearing this sound.

Susie: But this was a helicopter with the difference, wasn’t it? Because it apparently didn’t have doors.

Peter: No doors.

Susie: No doors entirely.

Peter: Door less. which for someone who has an issue with height and isn’t always the best at not dropping bits of recording kit, it was suboptimal, I’d phrase it like that. to be. To be fair, though, you know, pilot Zak did spend the entirety of his safety briefing on the subject of the doors. His safety briefing consisting wholly of asking me whether I was all right with no doors,

Susie: Man or mouse?! And presumably, I mean, it meant you got to see the region pretty close up.

Peter: Yeah, pretty close up close. I think I was. I reckon I could still have got a

00:05:00

Peter: pretty decent feel with a full set of doors, if I’m really honest. But anyway, I don’t want to complain, you know, where’s the thrill if I’m not clinging white knuckle onto my safety belt as we roll on our side to make another steep, high speed turn over the Gulf St. Vincent. And there’s nothing between me and the sea but a couple of seagulls and the sound of my, you know, stomach dropping through my boots. Anyway, enough of my man mousery. it was indeed an amazing way to get a, sort of feel for the region up on high.

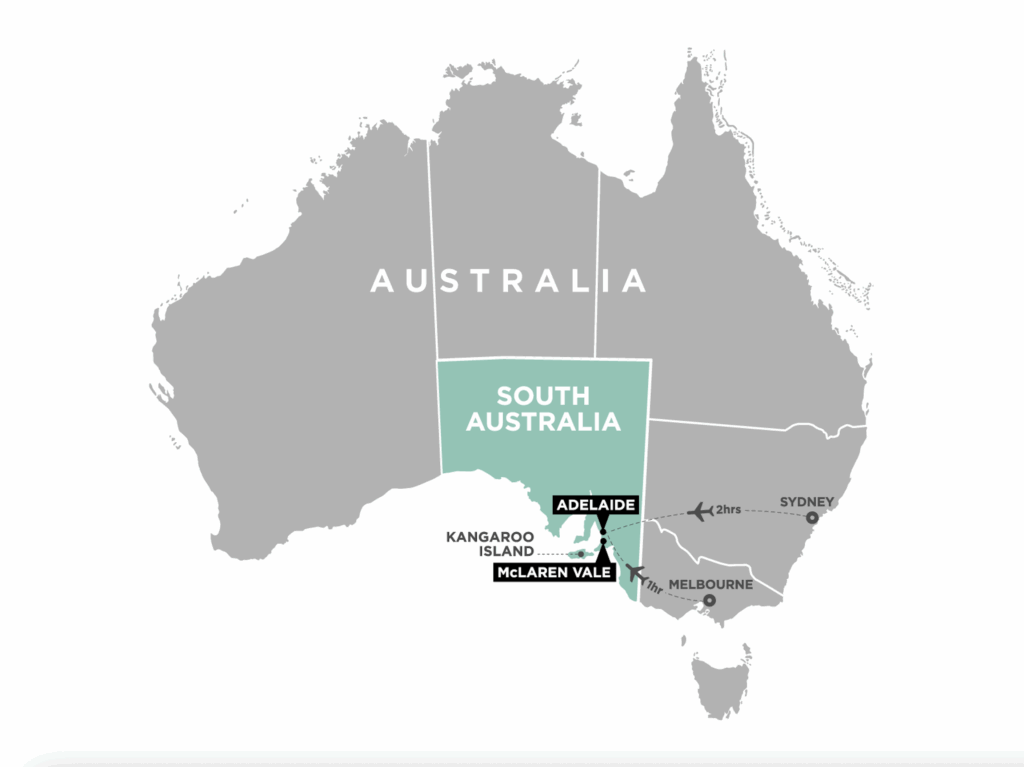

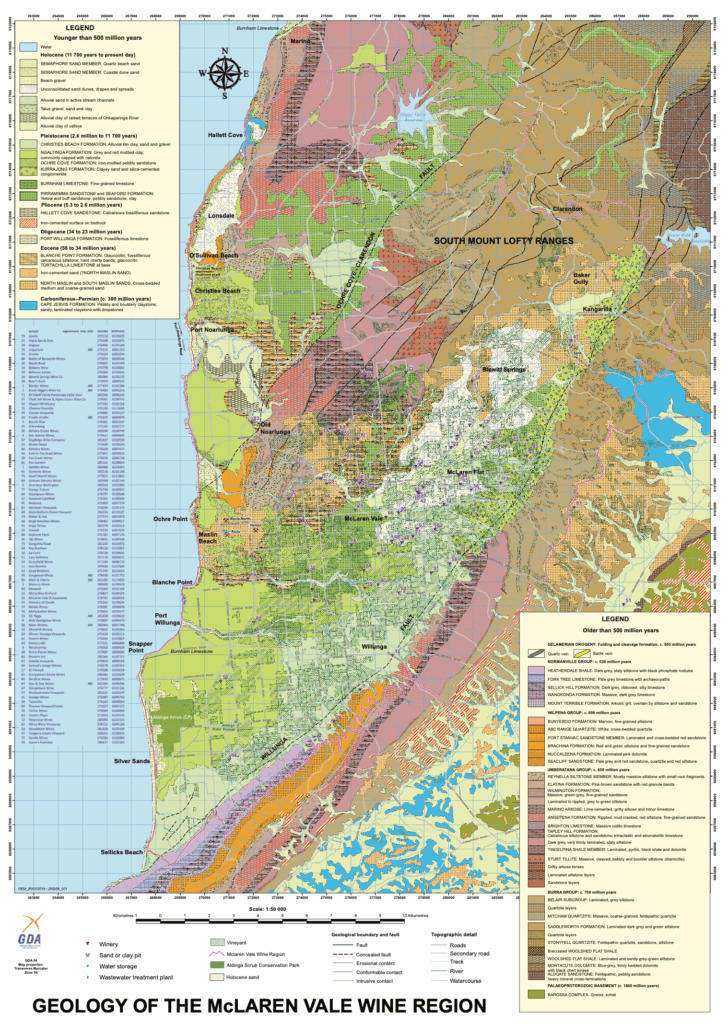

Susie: Yeah, well, let’s move swiftly on from your sky high stress levels to setting the scene, shall we? Now, McLaren Vale is one of the key wine regions in South Australia. It lies immediately south of Adelaide. And the bulk of the region’s vineyards grow between, between two geological fault lines that run inland from the Gulf of St. Vincent in the west up into the hills in the east across a, dizzyingly wide range of geologies and soil types.

Peter: And right there, you’ve got the essence of McLaren Vale. A whole range of microclimates, soils, exposures and elevations in this kind of lozenge of land that runs from the beach to the hills, which is, as I can confirm, stunning to see from the air. generally speaking, this is a pretty warm, dry place, but it’s tempered by the influence of the nearby sea, particularly with its afternoon breezes and the effect of altitude in the higher eastern parts like Clarendon. Here’s how Mary Hamilton of Hugh Hamilton Wines describes McLaren Vale.

Mary Hamilton: I think of it as being one of the best places on planet Earth where you could grow grapevine. And, and that is because of its incredible piece of geography. It is flanked by the Southern ocean and the Adelaide Hills, which creates this almost perfect bowl in the middle with a patchwork of very diverse ancient geology and about 20 different soil types that sit on top, with wonderful cool breezes that blow in from the southern ocean in the afternoon and, and cool temperatures that crawl their way down off the top of the Adelaide Hills, which put that with the warmth that the sunshine here gives us, means you ripen a grape, but you allow some refreshing coolness to prolong the ripening and give them a break. So for me, if you can’t make good wine here, I think you should go and get a different job.

Susie: No pressure then. So you get the sense of a, scenic region with rolling vine covered hills, the beaches nearby, the hills on the skyline, the big city within striking distance.

Peter: It’s definitely all of that. And of course we will get into more detail of this, you know, in due course. But there’s something else you notice quite quickly about McLaren Vale and its wine scene, and that’s the people. It’s, really quite a diverse, sort of cosmopolitan. Curious, I think, is a good word, community. And when you ask winemakers, to sum up McLaren Vale, this is a point that keeps coming up, and it’s quite telling, you know. Stephen Pannell is one of the region’s best known winemakers. he’s originally from Margaret river, actually not a bad spot in itself. He also lived in the fun part of Sydney, so when he had to haul himself to South Australia to study, he was determined to leave as soon as he could. Decades later, he’s still there. And this is what he said when I asked him what McLaren Vale is to him.

Stephen Pannell: That’s where my soul is. And I think for an Australian having a connection to country as a people that were translocated from somewhere else and dumped into this place for merely 200 years, yeah, it’s a connection to land. And I suppose that’s the beauty of wine, that wine expresses that love for place. So from the minute I first went there, I fell in love with this place by the ocean, which is where my soul is. I get in the ocean every morning when I wake up and I’m down there. Yeah. And it feels restored or it of being on my land. So I. I love McLaren Vale.

Susie: And that must inform the wine. Right. You know, if. If this is such a beautiful, special place with nice weather and a diverse community, then that’s going to have an impact on the wines that these people are making.

Peter: Yeah, yeah, spot on. here’s how Matthew Deller MW, CEO of historic McLaren Vale producer Wirra Wirra, sums this up.

Matthew Deller MW: McLaren Vale is a playground. So, as a wine lover, McLaren Vale is an amazing place to make wine. you can grow so many different varieties. It has so many different geologies and climates, and topographies. So you can kind of make everything that you could possibly dream of here in McLaren Vale. I mean, McLaren Vale wines can be very serious, and McLaren Vale wines can be very fun. and I think that’s part of what makes it a playground, that it’s not just a playground of different terroirs,

00:10:00

Matthew Deller MW: but it’s also a playground of very different winemaking philosophies. You know, McLaren Vale has always attracted, a lot of people from overseas, and, you know, from different cultures and walks of life. And so the McLaren Vale winemaking landscape is really Exciting as well. Very dynamic.

Susie: So we’re talking about not only a landscape that lends itself to making a diverse range of wines, but also a set of winemakers who are keen to Express that in the wines.

Peter: Increasingly so and for many different reasons, as we’ll, discover. One winemaker who made this point was Elena Brooks. Ah. Winemaker and owner at Dandelion and Heirloom Vineyards, who’s originally from Bulgaria. she came to study winemaking. She’s from a wine background and is another one who never left. And, this is how Elena related the place and the people to the wines.

Elena Brooks: I always say to people, come and. Visit because it’s one of those regions you have to see, because once you see it, you. You eat what we eat. You go to the beach where of, what we do as a daily life. You get it, you understand why we make the wines. We make as well. The wines are of such a high. Quality, and they’re so interesting. They capture the region, they capture the generation, but they’re not pretentious. There’s a sense of it’s. It’s, It’s quiet luxury, quiet luxury. Yes, because it’s not screaming in your face. It’s quiet luxury. Wines that are made here are luxurious. They are. They contribute to. To that quality. But they. They’re quiet. They don’t have to yell it. They don’t have to be, you know. The Yara Valley or. They don’t have to be. They’re quite luxury, quiet luxury.

Susie: not sure I’m quite trendy enough to know exactly what that is, but it makes total sense in wine terms. You know, unpretentious, but incredibly satisfying.

Peter: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And Elena was making the point that, you know, because this community is diverse and welcoming, there’s a lot of young talent coming through as well. Richard Leask of Hither And Yon described McLaren Vale as a good collector of creative souls. but this brings me back to the Adelaide bells we heard at the beginning. Remember those? And you were very keen. I explained a bit more about them, which is fair enough, because Adelaide is known as the city of churches. not actually because it has so many churches, but because historically the city was known for its religious tolerance across all kinds of faiths.

Susie: And wasn’t South Australia one of the first places to give women the vote, too?

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. That as well. So, you know, in a way, that sound of bells has a resonance that stretches beyond religion and kind of helps depict and convey the feel of the community and place as well.

Susie: So quite open. As we’ve already said, diverse, tolerant, welcoming. And people often talk of the Italian influence in McLaren Vale, as opposed to, say, the Lutheran German cultural background of the Barossa. On which note, we should probably briefly explain the history of McLaren Vale while we’re on this topic.

Peter: Absolutely, absolutely. History, history. so, you know, briefly raining in already. So, before the Europeans arrived, this was Kaurna country, and Kaurna is spelt K A U, R, N A. and another one of the first things I experienced in McLaren Vale was a beautiful welcome to country by Alan Sumner and his nephew Drew at the Serafino Winery, where we were judging the McLaren Vale Wine Show. Alan lit some tea tree leaves in a pithy bowl and carried a feather from a yellow tailed black cockatoo. And here’s a taster of what he said.

Alan Sumner: as part of our welcome to country. It’s normally people that are travelling through or passing through is that what we like to do is acknowledge the country that you’re standing on and the land that you. You’re on here today. So. So greetings to all, ladies and gentlemen. Are you all well today? Very good. In the Kaurna language, the local language of this country, you say manii. So are you all good today? Very good also means that you’re good, you’re rich and you’re fat, okay? But when we talk about it, we’re talking about our country. Our country makes us rich, our soil. makes us rich. And, if we have healthy country, we are a healthy people as well. So, McLaren Vale, absolutely beautiful place. so, yeah, on behalf of my family and my ancestors, it’s good that you are here. today on Kaurna country, we call the country Yarta. and so, like I said, doesn’t matter where you come from, you’re welcome. Here on our country. Natalia. Thank you.

Susie: Healthy country, healthy people. Very well said.

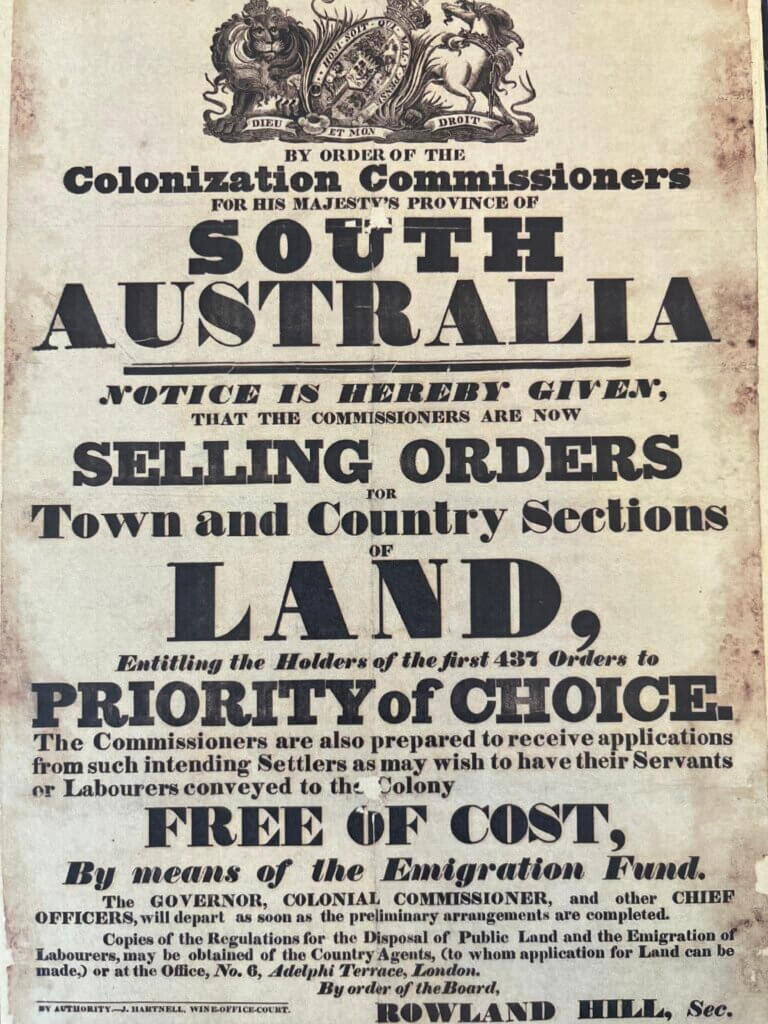

Peter: Yeah, yeah, we’ll come back to that. Alan reminded us that his ancestors were no strangers to fermented drinks. but it wasn’t until the 1830s that Vitis vinifera arrived along with European settlers. Now, South Australia was one of the first free, so not a penal, colonies.

00:15:00

Peter: People, came in search of a new life and to make a living off the land, be it in sheep farming or gold mining or whatever. And one of those people was John Reynell.

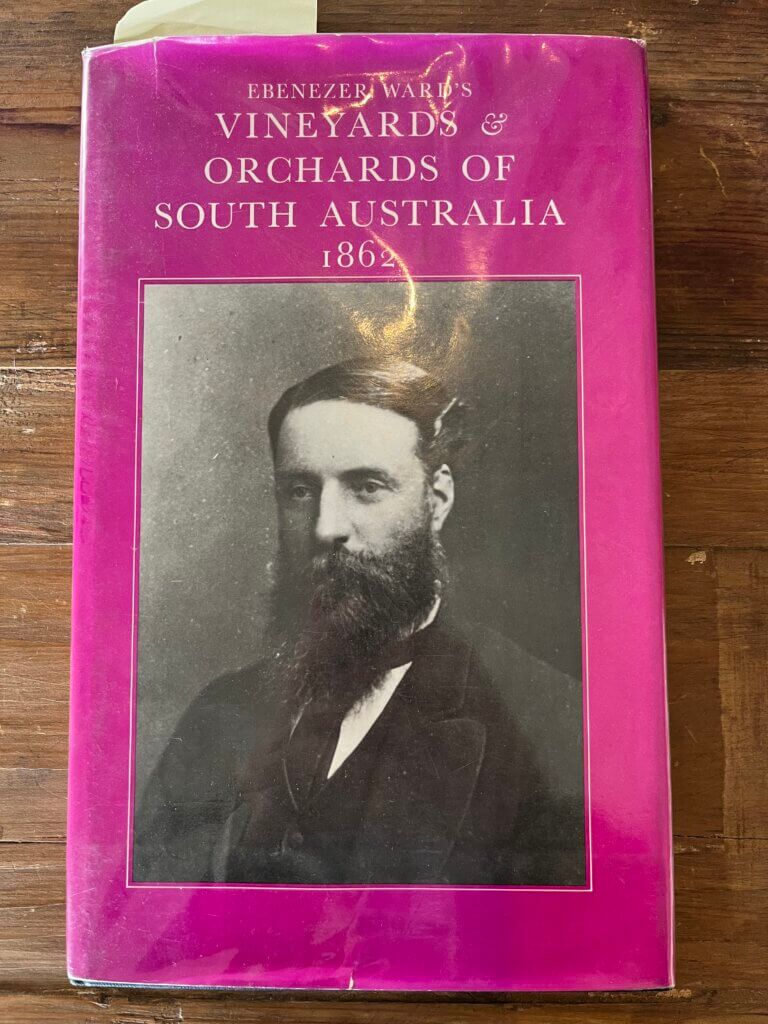

Susie: So Reynell was a farmer from Devon who arrived in 1838 and planted grapevines shortly after. Now, he’s important to the story because in 1850 he hired one Thomas Hardy, also from Devon, to be his cellar Hand. Hardy was clearly something of an entrepreneur because by 1863, he had a 35 hectare project of his own. And in 1876, he bought the Tintara Vineyards Company in McLaren Vale off Dr. A.C. kelly, another viticultural pioneer in South Australia. By 1900, Thomas Hardy and, sons was one of the largest producers in South Australia. And, of course, Hardy’s remains one of Australia’s biggest brands today.

Peter: Now, we’ll come back to Hardy’s and Tintara in a bit, but another name to mention here is Richard Hamilton, a, tailor from Kent who emigrated with his wife and eight of his nine children. Wow. by all accounts, he was also one of the first to plant winemaking vines in South Australia. but the question is, why would a tailor from Dover sail to the other side of the world with his rather large family? it’s not entirely clear. in truth, though, his great, great, great. I think I’ve got that right. grand daughter Mary Hamilton, who you’ve already heard from, told me it may have had something to do with him getting in hot water over a wine smuggling side hustle.

Susie: The plot thickens. Love it. Now, McLaren Vale got its name from John MacLaren, who surveyed the land in 1838. And the early days were not easy for vine growers who became locally known as ‘plonkies’. but it does seem that the likes of Shiraz and Grenache are arrived pretty early. And to be honest, Australia made a name for wines of all styles, from sparkling to hearty Burgundy, often made from Shiraz and Grenache. But fortified wine production also grew, hence the spread of varieties like Doradillo Palomino, Pedro Jimenez Muscat, etc.

Peter: Now, luckily, varieties like Shiraz and Grenache could be used in different styles, so they stayed in the ground. Plus, South Australia has never succumbed to the dreaded Phylloxera pest. That meant most of the world’s vineyard had be replanted using American rootstocks. What this means is that South Australia, including McLaren Vale, has some of the oldest surviving winemaking vines on their own roots. Which is quite something.

Susie: Yeah, I mean, invaluable cultural heritage right there. Vines that have been producing grapes for over 100 years, in some cases nearly 200 years. I mean, it’s quite a thought, isn’t it? So, in the mid 20th century, with the advent of electricity, modern techniques and changing tastes, production started to switch back from fortified to table wines. And McLaren Vale made a name for itself as the mid palate of Australian wine. I mean in other words, producers would buy McLaren Vale fruit and use it as part of bigger cross regional blends to give them flesh and body.

Peter: M at the very top end. Penfold’s Grange, one of Australia’s most iconic wines, famously uses a fair bit of Maclaren Vale fruit, even though it’s not mentioned on the label. But, but McLaren Vale was also arguably in danger of fading into semi obscurity by making straightforwardly hearty reds and building other people’s brands. Stephen Pannell said when he arrived to study at Roseworthy, McLaren Vale was suffering from what he terms an identity crisis.

Susie: And this is where the story gets interesting because after the turn of the millennium a new breed of producer like Stephen Pannel, as well as some enlightened older ones realised this was not the only. So they started looking to their old vine heritage at their viticultural and winemaking practises at ah, things like sustainability and water and terroir and to what new grape varieties might work well in McLaren Vale to shake things up a bit.

Peter: Now this has led to a dramatic uptick in wine quality and personality with elegant single vineyard wines made by ambitious smaller producers becoming the standard bearers for the new McLaren Vale. We’ll get more into the detail of this in the next episode. But essentially McLaren Vale has gone from having an identity crisis to a full blown wine renaissance.

Susie: And what’s quite pleasing is that the history forms part of that renaissance. The most obvious example is in the amazing old vine resources in the Vale, particularly Grenache. But remember Hardy’s and Tintara? Well, Andrew or Ox Hardy is today a fifth generation Hardy winemaker. He sells most of his fruit to the big Hardy’s

00:20:00

Susie: brand, but also keeps some choice cuts for his own Ox Hardy label. And what he’s also doing is using some of the surviving vats from the winery his forebear built in 1863 to make one of his wines.

Ox Hardy: The vineyard was first established in 1861. There was a winery built here in 1863 and we have the ruin of that winery. Sadly, most of it’s gone but I’ve still got a couple of the walls and three slate fermenters. So they’re open fermenters that were built out of slate and these fermenters were built in 1863. They were used from 1863 to 1928 in the winery and then they went into disuse and I cracked. We cranked one up in 2018 and then another one in 2019. So we used two of these 1863 fermenters to make the Slate Shiraz. so that’s really good fun. I mean, the fact that I’m making wine from a vineyard that my great, great grandfather mucked around in and, and a winery that was built all that time ago is pretty neat. It’s really good fun, spiritual,

Peter: my kind of spirituality. right, next up, we’re going to move from history and spirituality to things like old vines, sustainability and the intriguing way in which McLaren Vale is defining its terroir. diversity. Always a thorny issue that gets people very hot under the collar. To recap, so far, McLaren Vale is a historic wine region in South Australia which has gone from identity crisis to exciting renaissance in just a few decades. Based around a treasure trove of old vines and a dynamic, diverse wine community. And, did I mention it looks great from a helicopter with no doors?

Susie: That’s, not quite how I remember you telling it, but let’s move on and home in on how McLaren Vale has been on a journey of self discovery in recent years. It hasn’t been entirely pa, but it’s helped both producers and drinkers develop a newfound appreciation for the Vale’s wines, as well as building a firm foundation for the future.

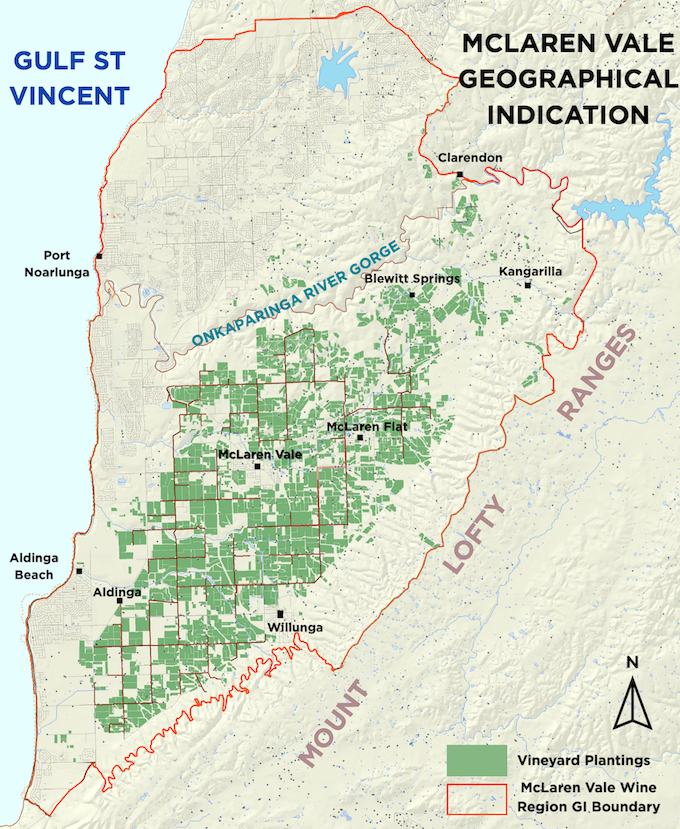

Peter: You make it sound like therapy. but yes, this is the, Districts programme, aimed at, understanding and promoting McLaren Vale’s various terroir. Now, McLaren, Vale, it’s not a big region, but from beach to hills, grape growing conditions change. Add to this the region’s complex and highly varied geology and soils, and you get what local winemakers have long known, that different parts of the Vale give different styles of wine, even from the same grape variety.

Susie: The issue here is that as soon as you start to try to define these things, you hit two problems. Firstly, taste differences are hard to prove empirically or scientifically. And second, people start to get a bit shirty if they feel their vineyard is the wrong side of any particular dividing line that’s going to be drawn on a map.

Peter: It’s too true, isn’t it? Human nature. But the way they’ve gone about the districts programme in McLaren Vale is very sensible to my mind. the region had detailed geological maps, so they used those as the starting point for outlining different areas, what might be different districts. They also overlaid data on things like topography, elevation and climate. But most importantly, what they’ve then done is taste the wines from the different districts repeatedly and over years have built up a sort of profile of how they subtly differ.

Susie: And they’ve developed a particular way of tasting to do that, haven’t they?

Peter: Yeah, it’s a good point. It’s a good point called pivot profile. I don’t understand it all, but from what I was told, what they do is they get winemakers from all over the Vale to submit wine samples. It’s voluntary. they’ve just focused on Shiraz. So far as the most widely planted variety in the Vale, shiraz is actually 56% of total plantings in McLaren Vale. They then make a regional blend to use as a benchmark from all those wines. And then they taste the samples from each district and say, more or less red fruit, more or less mark tannin, whatever, that kind of thing. Very specific kinds of questions that can then produce sort of data led conclusions and profiles.

Susie: So I guess the real question is, why bother? What’s the point or the ultimate aim, ah, of this?

Peter: Yeah, it’s a very good question. So I talked to Drew Noon MW of Noon Winery, who’s been involved in the district’s programme.

Drew Noon MW: It’s sort of obvious to everyone who lives and works here that the wines are slightly different in different parts, but no one’s really, studied it, as it were, or put it on paper and whatnot. And everyone is aware of the diverse of the. The focus on terroir in the historic regions of Europe. And it’s almost like you think, could it be that diverse here? And what does it look like? And it was like a, It’s a wonderful journey and discovery to sort of. We, I think that we’re on and have started to. To discover and elucidate, define the differences that we really have a diversity of terroirs as they would be known in the old world in McLaren Vale. That, are fascinating and we’re starting to define. So put lines on maps, but also descriptors to the characters of the wine. So

00:25:00

Drew Noon MW: they’ve been there all the time, but we sort of weren’t looking in a focused way. And now we are. And it’s really exciting. We’re developing all this knowledge about how the wines are different in macramer and.

Peter: What’S the point of all of this? Where is this heading?

Drew: Yeah, well, really, it’s fairly simple. It’s a lot of work to try to, get to a point where you can say the wines from this side of the valley and this part of McLaren Vale tastes like this, typically. And if you get a wine from this part, it’s typically going to taste like this, a little bit like in Bordeaux or in Burgundy, of course, and. And so on. You have typical characters. This is not going to apply to every wine, but it’s good. I find it really helpful because if you have a reference point or what to expect, it helps you to interpret the wine that’s in front of you in the glass.

Peter: And as far as I understand, though, the aim isn’t necessarily to set up some properly legally defined sub regions within McLaren Vale, is that right?

Drew: Yeah, true. It’s sort of a. Sort of a technical point, if you like. But, sub region, which is what we would refer to these as, has a legal definition. So it has to have, you know, a certain amount of vineyards, a certain amount of wine producers. The lines are drawn on the map, registered with the, authorities, and you can’t change it. Whereas initially, at least, what we’re doing is loose. We’re not going to call them sub regions, we’re not going to define them legally. We call them districts. We can change them at will because the work in progress, it may eventually lead to sub regional definition.

Peter: And how important is this work for establishing McLaren Vale as a fine wine region?

Drew: I think it’s really important. The bigger question is, does anyone care? That’s what the cynics say to me. And I think, yes, they certainly do mean. Look at you and me, complete wine nerds. there are plenty of people who love wine enough to want to know more and more and more. Why wouldn’t you? It’s absolutely fascinating, the fact that grapes grown in one little corner taste, produce wine that tastes different to. If you grow them over there, it’s just. It’s just wonderful. That is a. It’s like a connection with the planet. You know what I mean? It’s marvellous. But it is pretty nerdy and not everybody cares, and that’s fine. But if you want to, and those who care a lot and can’t get enough information, then you can drill down. And of course, if you’re paying more than, you know, $30 in Australia or whatever, people tend to want to. They get more and more fussy about how much they want to know the more m. The Boris goes on. So if you’re talking about high quality wine or expensive wine, let’s say, then people want to know, I think. And so, so. And we want to know. So hence the work. Yeah.

Susie: So this is really important. You know, we accept the different vineyard crus in Burgundy or Bordeaux’s sub regions, without question. But at some point, they must have had to be agreed upon and codified to some extent. And that couldn’t come without a sufficient focus on quality that the differences were able to be perceived in the wines. So really, this is about establishing and promoting quality credentials in an ever more competitive global wine market.

Peter: I think that’s definitely part of it. and it makes total sense, isn’t it? You know, it’s absolutely the right way to go, I think, you know, as is the very gentle, gradual way that they’re going about it. You know, there are dangers in trying to rush these things as other Australian wine regions have found better to be, you know, cautious and collaborative and let this kind of thing evolve and establish itself over time.

Susie: And I think Matt Deller was talking about this, that one of his aims at Wirra Wirra is the burgundification of fine wine in McLaren Vale. You know, focusing on single site, even single block wines and establishing a reputational hierarchy. You know, get people talking about the different districts and the best vineyards within them. It reflects well on the region.

Peter: Yeah. And Mary Hamilton had a great metaphor when she was describing three different Shiraz wines in her portfolio from different sites. So the style of wine that comes from near the Hugh Hamilton cellar on cracking black clay soils is the boxer, whereas the style from just down the road off more alluvial soils is the burlesque dancer. and finally, the wine from up in the hills of Blewitt Springs off sandy soils, gives, the ballerina. I loved that way of picturing it.

Susie: And just to put a bit more flesh on these bones, Drew was explaining that some districts are better defined than others at this stage, partly because they’ve more samples to work with from certain areas than others. So districts like Clarendon Rocks in the eastern hills, Blewitt Sands also in the East. Onkaparinga Rocks, Gulf View, Willunga foothills. These are all districts we’ll be hearing more about in the future.

Peter: Yeah. And to focus in on one of those, Clarendon, I talked to Toby Bekkers of Bekkers Wine Local. boy Toby married French winemaker Emmanuelle after they worked a vintage together at Tintara in 1995. And before long, they’d set up on their own. Initially, they blended wines from across the vale. But when a chance came up to buy the historic Clarendon Estate vineyard high up in the eastern hills, they leapt at it, despite the vineyard being

00:30:00

Peter: abandoned.

Toby Bekkers: So when we bought it in 2020, it hadn’t been touched for seven or eight years, not pruned, not watered, was a bit of a basket case place full of blackberries, full of giant kangaroos that just lifted a, head and looked at us and said, who are you? We’ve been living here quite happily for ten years. so it’s been a massive reconstruction job. But we think it’s going to be, you know, you know, one of the great kind of wine estates again of McLaren Vale. And that’s why we’re here. And it’s quite unique, soils wise, climate wise. It’s really much cooler and feels probably more like the Adelaide Hills if we’re, if we’re being realistic. If you look at the native vegetation here, it’s much more bluegum and Adelaide Hills type vegetation than it is McLarenvale probably.

Peter: But why are you going to all this trouble? What do you think the wines here will be able to give?

Toby Bekkers: So if you think back to our purpose originally, it’s to be a real fine wine beacon for McLaren Vale. We know that Clarendon gives wines that are, lighter framed, prettier, more aromatic. And we just think that fits a fine wine kind of brief a little more than making something that’s purely about muscularity. So I think 10 years ago you would hear people talk about if you made an expensive wine in Australia, you would hear the word power a lot. It’s got the power to be an expensive wine. These days in our business at least, we talk to each other a lot more about persistence. And I think they’re totally different things. So wine can be lighter and prettier and aromatic, but still have amazing persistence. And I think that that’s what a. Fine wine is to us,

Peter: trying to express a place. how important is this in McLaren Vale and what are the key elements that go into expressing a place successfully?

Toby Bekkers: There’s two parts to that question. The first is the actual site you choose and the slope and the aspect and the water holding capacity and where far you, are from the coast and all those things, you know, that we call Tehra and talk endlessly about. But often I think we forget about the space between your ears, which is your intention. so if you do give someone the same grapes, or you do give someone all the ingredients to bake a cake, you give it to 10 people, there’s only a handful you’re going to want to eat, I think. So the human element is so important as well. So our intention, I think, is massively important in, in what we’re trying to do here.

Peter: And, and just to, just to remind ourselves what is your intention here?

Toby Bekkers: So our intention is to showcase McLaren Vale’s fine wine credentials. and I think part of that is just having confidence in yourself and in your region. So the confidence piece is massive. You know, you’ll often hear people say, oh, we, we think we make wines equal of anywhere in the world. And then they sell them for 30 bucks. Bucks. And to me, that there’s, you know, once you’ve done that, you’ve blinked. it’s a. It’s a big poker game and you’ve got to show the confidence you have in your region.

Susie: So lots to pick up on there. Firstly, it’s great. They’re restoring this amazing vineyard to its historic glory, which was first planted in the 1840s, I believe, and made quite a name for itself. But also, I love his point about human intention being a vital element in the expression of place, and how that’s about making wines with persistence rather than power.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. I mean, so often people talk about terr as if human intervention doesn’t exist or doesn’t happen, but it does, and it’s a crucial part of the process. As to his point about confidence, you know, I really endorse that. You know, you’ve got to back yourself. and I think, you know, zooming out a bit. Australia right now as a whole needs to back itself. It’s never made better wines than it is now. It’s not an easy market to sell into. But what you hope is that quality will win out ultimately. So I think confidence and perhaps a bit of patience are key virtues, I think.

Susie: But Toby also linked that to price, didn’t he? And some of the Becker’s wines, particularly the Clarendon ones, are pretty pricey.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. They’re not cheap. up to about, 300 Australian dollars, I think, so about 150 quid or 200 US dollars. Ish. But, you know, I tell you what. What? They’re also pretty bloody magical. and you could argue, you know, in a global fine wine context, they’re not overpriced compared to some others. you know, I tasted both the 2023 Bekkers Clarendon, Syrah and Cabernet the first wines off this, this revived site. And they are stunning. They are really amazing. They’re so elegant, so perfume, so well defined, so, so, so fine and regal almost. And it’s great because, you know, being there, you can see how hard the vineyard is to work. Work. It’s incredibly steep. There’s no power there and all this sort of stuff. But, you know, These guys are good and they’re determined and they’re going back to that word intention really shines through in those wines. So this is a great example, I think, of how McLaren Vale is becoming more diverse and quality focused.

Susie: And one other thing I think we should touch on here, perhaps briefly, because I know we’re going to explore this in the next episode, but it’s the subject of old vines.

00:35:00

Susie: we’ve mentioned the history, the lack of phylloxera. Ox Hardy, who we heard from, has vines from 18, 1891. He still uses. and I believe some of the oldest vines in McLaren Vale are thought to date back to 1887. I mean, isn’t. Isn’t there some sort of register?

Peter: there is, there is. I think we’ll put a link on our show notes because it’s quite something to read through. it’s mainly old vines and mainly Shiraz and Grenache, but there’s also some historic Mataro or Mourvedre, Chenin Blanc, Sangiovese, Sagrantino, Cabernet San Serres. It’s a fascinating list. they’ve got something like 270 plus hectares of old vines officially registered so far in McLaren Vale. But it’s thought that the true number of vines over 35 years old in McLaren Vale is roughly a thousand hectares. this out of a regional total of 7,335 hectares, by the way. So, you know, that’s quite something.

Susie: Yeah, I mean, real viticultural history there. But the real question is what difference those old vines make to the wines themselves. David Gleave MW is, is founder of Liberty Wines, a distributor in the UK, but also part owner of Willunga 100, which is making some outstanding McLaren Vale Old Vine Grenache. This was his pithy summary of what old vines mean for the wines.

David Gleave MW: Well, they just give you so much. More depth, layers, structure, better tannins, and they’re better able to cope with the sort of dry conditions in which Grenache thrives.

Peter: That point about old vines being able to survive stress better is a really important one. You hear winemakers citing a lot, actually. But to delve a bit deeper into this, I also asked this same question of Giles Cook MW Giles, is based in Scotland, but divides his time between there and Australia because he’s owner of Thistledown Wines, which this year won the best wine in the Maclaren Vale Wine show, which I was obviously helping judge for their Sands of Time Blew It Springs Grenache. So it Goes without saying that Giles makes superb old vine Grenache in McLaren Vale. And this is what he said when I asked him what difference old vines make.

Giles Cooke MW: This is where I guess the contrarian comes out in me, a little bit because the received wisdom is that old vines give power, concentration that don’t exist in young vines. and there are elements of that that are true, but it’s not what I get from old vines. I mean on a very superficial basis, you walk through an old vine vineyard and you can immediately kind of sense all the history, the people that have been there before. as somebody that likes telling storeys and creating labels and that kind of stuff, it’s, it’s a gift. so old vines give you that advantage. That certainly is an advantage for me. but old vines adapt to their site. and I always try and explain it to people by saying, forget the fact that they’re a vine that’s growing grapes to make wine. They’re a plant and a plant wants to survive. and it wants to reproduce and the vine reproduces by making their fruit more attractive than anything else. So that a kangaroo or a rabbit or whatever a bird comes along, eats the fruit, poops it out somewhere else and it’s done its job. And over a long period of time, vines adapt to their environment to ensure that they reproduce ahead of other plants near it through epigenetics, the sort of the building blocks of evolution. And for me what an old vine does is because it’s more adapted to that site, is that it attracts animals to come and eat its fruit by pushing flavour ahead of sugar so that it attracts, if it senses it’s going to be sort of water stressed or it’s going to be too wet. M. An old vine will push flavour ahead of sugar so that it has a better chance of reproducing. Now the benefit to me of that as, ah, somebody that wants to make wines that are energetic, bright, floral, more moderate in their alcohol and more balanced is that I get flavour before sugar in old vine that I wouldn’t in younger vines. so actually for me the benefit of old vines is that I can pick them at an earlier point when the fruit is healthier, the analysis is much healthier. So I have to do less in the vineyard and overall you could just get a much better result.

Susie: So older vines mean earlier ripening fruit which can mean it’s easier to make more elegant, medium bodied styles without excessive alcohol and that, that’s one of the key trends coming out of McLaren Vale right now, isn’t it? You know, this emphasis on drinkability, refreshment value, medium bodied wines that aren’t excessive or

00:40:00

Susie: heavy.

Peter: Yeah, I mean, we heard Toby Bekkers touch on that too, didn’t we, with his point about persistence rather than power. And now, you know, as Giles said, old vines aren’t the only way to achieve that, but they can certainly help. one winemaker said, you don’t get your best work out of a teenager. Ain’t, that true? this particularly applies to Grenache, where younger vines can often make quite simple two fruity wines. you can make decent wine from younger Grenache, but it needs a lot of work. Plus, you know, as Giles said, the old vines also enable you to tell a story just like we’re doing here.

Susie: And that in itself is hugely valuable for a region that’s building a new identity for itself on the world wine stage. What’s also important in terms of the wider story is sustainability. and this is another big thing for McLaren Vale, isn’t it? On many fronts. But, but take organic, biodynamic and regenerative cultivation. These practises are now a key part of what McLaren Vale is doing. One stat that struck me is that 40% of McLaren Vale’s vineyard is certified organic or biodynamic. Now that’s pretty high in global terms and apparently the highest in any Australian wine region.

Peter: Yeah, yeah, and a fair bit more is run along those lines, but not certified. So, you know, it is impressive. it certainly seems like it’s something taken pretty seriously here, perhaps, maybe, don’t know, reflective of that cosmopolitan international outlook among the wine community we talked about. I don’t know. But, you know, for example, Wirra Wirra now have all their estate vineyards as organic and biodynamic, managed regeneratively. Plus they’ve hired a sustainability manager. They use solar panels, they recycle their winery wastewater. and, they’ve lightweighted their proprietary bottle from 550 grammes to 410 grammes. They’re also signatories to the bottle weight accord and the sustainable wine round table.

Susie: And one of the other things to mention in terms of sustainability in McLaren Vale is water, isn’t it? And such a key resource, especially in one of the driest places on earth as Australia and indeed South Australia is. But McLaren Vale has been something of a pioneer on this front and it realised pretty early on that drawing water from the underground aquifer was Wouldn’t last forever, particularly if the inflows were gradually declining with climate change. So they voluntarily capped extraction levels in the 1990s. But not just that. They also benefit from one of the first projects of its kind whereby recycled wastewater from Adelaide is repurposed to be used by wine growers. And that is not a small undertaking, is it?

Peter: No. apparently Two thirds of McLaren Vale’s viticultural irrigation needs is met by this wastewater recycling infrastructure. I mean, that’s huge. I mean, you know, imagine if this were rolled out worldwide. So in the same way that Bekkers is aiming to be a fine wine beacon for Australia, this kind of thing is surely a, you know, a sustainability beacon for the wider world.

Susie: But just considering water and lack of it, didn’t you find yourself talking about water shortages with Richard Leask from Hither and Yon in the middle of a massive thunderstorm?

Peter: Thanks for reminding me. You know, the cosmos has a sense of humour sometimes it seems. Are you quite right? we’d arrived to meet Richard, who had the most beautifully restored Land Rover Defender ready for us to cruise around the vineyards and, you know, talk sustainability and water conservation. Whatever. Only problem was it was open top and by then it was absolutely honing it down with rain, proper stair rods, with thunder and lightning, a proper health and safety risk.

Susie: I bet Pilot Zak wouldn’t have blinked in either.

Peter: Pilot. You’re absolutely right. Pilot Zach would have just launched.

Susie: He just gone.

Peter: I am not cut from that same cloth, clearly. So we retired, sheepishly to a sort of shed come office, while all this was going on around us.

Susie: An unseasonal downpour, I’m guessing, and maybe that kind of unpredictability and increased intensity of weather phenomena we associate with climate change. But going back to Richard, he is something of an expert in sustainability and regenerative farming, isn’t he?

Peter: He is, he is. He’s an absolute font of knowledge. So, let’s just hear what he said when I asked him about regenerative viticulture and what he’s doing and why.

Richard Leask: That stemmed out of a nuffield scholarship I was lucky enough to do in 2019. And it was just looking at farming systems globally that looked after the soil, you know, and not only did they look after it, they actually had a focus on, on bringing it back and working out how to bring back soil life, you know, for one of that bigger term. So the practises that do that now, you know, vineyards intrinsically are an intensive system. it’s a difficult system to Nail totally in terms of how to describe it. But I think bare soil gives you no photosynthetic capacity, so you need a plant on it. And if you don’t have something, if you continually make that place bare, the plants you end up with are the ones you don’t want, because they’re always the coloniser plants and

00:45:00

Richard Leask: they’re always the nastier ones. So once you get into a system of grazing, you graze them out, you end up with grasses and some medics is what we’ve done here. And all of that’s happened naturally because we’ve sort of just got out of the way and stopped intruding. and. And just sitting back and reading landscape is the other really important bit. you know, before rushing in to do something, ask, yourself, does it. Is it going to affect the soil structure? Is that going to be a positive or a negative thing? Is it going to affect soil biology? Is that a positive or negative thing? And if they tick both of the negative bits of the box, then you need to ask yourself whether you should be doing it, you know, and that’s what we’ve done. And it’s hard for. Farmers are very rhythmical, cyclical people. We run with seasons and the jobs need to happen at the same time every year. So to break that and say, I’m not going to go and do something I’ve been doing for 30 years, I’m just going to sit back and let this system have its way and read it and understand when I do need to intervene. Takes a little bit of practise and it’s a bit of conscious thought. And that’s what I like about that farming system. It requires conscious thought to do it.

Peter: So it’s a form of sort of. Conscious farming, reading the landscape, thinking before you do it.

Richard Leask: correct. I mean, I think quite often we just do stuff and we’ve all been guilty of it because that’s when we need to be doing that job. You know, we’ve got to do the herbicide or we’ve had vineyards that they need to look like this, they need to look manicured and, you know, everything in its right place and whatever. And now we’re just embracing a bit of chaos and finding out where the edges are, that where we need to intervene, and then finding quite often that we actually, if we just let it settle itself, we actually can just let it have its way. So it’s a. It’s terrifying and exciting and rewarding all in one, depending on what the season’s giving you.

Peter: And you Know, once you start to learn to read this system successfully and appropriately. Do you think this is the way forward for wine?

Richard Leask: Oh, I think it has to be. I mean, if we talk about. The whole thing revolves back to sort of soil, you know, and Australia doesn’t have any, you know, we’re, we’re just a lump of rock sitting out, you know, we were Antarctica and then all the ice left and then what we’re left with is weathered stone, essentially. So the topsoil we’ve got is so precious that we need to be building it. And we can only build soil if you have plants on it and you let biology do all that and then you get, you know, the mulch layer there and it breaks down and then, you know, over millennia you build some soil. We weren’t blessed with the great prairie lands of the States with high rainfall as well, so we need to manage that and work our way through it. So that’s a, that’s a production thing. So if we can raise, if we talk about carbon, because highly productive soils are high in carbon, if we can raise carbon levels, then we raise the production capacity of the soil, which means there’s more for everyone, more for the plant story underneath, but also more for the crop we’re trying to grow, which in this case is vinegar wines. So there’s a win, win for everyone. And I don’t think there’d be a wine region in the world that’s not under pressure with cost, that if we can. This system, which we’re, we’re pretty comfortable, we’re taking things out of it as well. You know, every time you don’t drive a tractor through there, it saves you money. so it’s a win for the environment and a win for the back pocket. So I think if you’re not thinking about, how you can increase the capacity of your soil, then life’s going to get harder.

Susie: fascinating. I’m intrigued by this concept of conscious farming. Knowing when not to intervene as much as the opposite. And the fact it’s all about building soil so using cover crops and animals to graze them and how this can make for a more efficient and cost effective system.

Peter: Yeah, I mean hither and yon are a, ah, fantastic case study in regenerative viticulture. they’re also replanting native plants to encourage beneficial wildlife, to control plants, pests, for example, using Christmas bush or bursaria, I think it’s called, as a habitat for native lacewings, which then eat caterpillars and moths. and they have boxes for micro bats, which are a thing, apparently, which, eat hundreds of insects a day. so pesticide use is almost zero. Now, Richard was Talking about how McLaren Vale has evolved from a place that used lots of resources, including water, to grow big crops, to sell to big brands outside the region, to a focus on, you know, smaller producers making wines that speak of their place. You know, based around attention to detail, vine health and, and sustainability, that kind of thing.

Susie: It’s exciting, isn’t it? And I guess these, these kind of sustainability initiatives work on two levels, don’t they? You know, firstly, to be responsible custodians of the land and our planet, to set an example, to show it can be done. And then secondly, you hope it’s also good for wine quality.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. And Mary Hamilton touched on this too. she’d mentioned that she really prizes sort of brightness and vitality in her wines, something she described as lightning in the glass, which is a lovely, image. I asked her to sort of unpack this a bit more and it ended up coming back to soil.

Mary Hamilton: Lightning in the glass is where when you take the sip of the wine, it feels like it is living and alive, which is different

00:50:00

Mary Hamilton: to a wine that has a more plodding sense of being static. Where does that come from? I think that’s the secret sauce. I think it starts in the soil. And I think that what we saw in viticulture historically, there was a lot of chemical additive that was being put into soil because people saw weeds as enemies. And so they wanted to get rid of them. They thought it was competition for the grapes. And so back, you know, in my father’s era, a good looking vineyard looked like a vineyard that was ploughed within an inch of its life and had a large lot of glyphosate put on, it to get rid of weeds that, in my opinion, was killing the soil. Now, if you kill the soil, I look at the soil in a vine a bit like an iceberg. The iceberg has all the action up the top. And we can see the vine with its leaves and its grapes up the top. But the majority of what is going on is happening under the earth. and that’s where the roots are and that’s where the life is. And there is a whole ecosystem going on down there. And if that is vibrant and alive, to me it just makes sense that the grape at the top is going to be a healthy, vibrant, alive piece of fruit. And if that’s the beginning of the wine making story as most people think it is. Well now we’re starting with a raw material that is going to taste like a piece of lightning in the glass.

Susie: And who doesn’t want a bit of lightning in that glass? I want lightning. I want fireworks, lightning and thunderstorms. But I do know exactly what she means and it kind of alludes to what Toby Becker said in terms of persistence, doesn’t it? It’s not power or heft or concentration, it’s energy and vitality that makes great wines. And if that comes from a healthy living soil, it makes sense to protect and nurture that.

Peter: Yeah, now we’re coming to the end but one thing I just wanted to mention before we close is wine tourism. this is a big thing in the Vale partly because it’s so close to Adelaide and it makes a great visit with the be beach as well. there are so many great cellar doors with restaurants and shops and exhibitions. I wasn’t going to mention this to not make you too jealous but you know, it’s a kind of wine loving tourists paradise. I’m sure it is, it is. But you know, one winery we particularly mention this in this regard is d’Arenberg. Yeah, Darenberg.

Susie: It is one of the historic wineries in the region. It has a treasure trove, doesn’t it, of old vineyards. It’s one of the largest biodynamic producers in Australia. It makes a dizzying array of wines, over a hundred labels from something like 48 different grape varieties. And it’s also one of the most iconic producers in Australia because of the cube, this remarkable five story visitor centre. Come exhibition space, come dining and tasting facility that’s frankly like a giant Rubik’s cube. I mean you explain.

Peter: Yeah, it’s hard to keep, it’s just something else else and really to understand it you have to get to know its creator. Chester Osborn, fourth generation winemaker at Darenberg, possessor of what is surely one of the most prodigious creative careering minds in wine today. early on in his life Chester was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, ah, and his mother was told to keep him busy with creative projects. He’s been a, ah, sculptor, designer and creative art artist ever since. He describes wine as an art form like any other and he says the following.

Chester Osborn: I actually use this philosophy that once you’ve explored one art medium to the nth degree, like wine for example, then really you can start looking at all other art forms in that same depth and really be Loving all the different types of art, so. And, you know, we’re a long time 6 foot under, you know, there’s a lot of life to live out there, a lot of life to see, a lot of art to see, I should say, and a lot of art to make. I’ve actually got about 600 sculptures that I’ve written down as ideas. Each of the art pieces I do in the, in the d’Arenberg Cube, there’s over 100 sculptures in there. Each one represents one of our wines or our, winemaking process or something to do with wine. So that. So when people come to the d’Arenberg Cube, they can really feel, feel, that wine is art and here it’s expression in a different form. So I call it the Alternate Realities Museum. So there’s all these, alternate realities of the, of the wines,

Susie: A lot of life to live and a lot of art to make. What a positive note to end on. We’ll put photos of the cube on our show notes and if you ever get the chance, do go and visit. It’s quite remarkable, not to mention tasty as well, because there’s some delicious food and you can blend your own wine and gin. Plus, Chester tells us he’s got three more buildings to build before he dies, so there’s more excitement coming too.

Peter: and talking of more excitement, don’t miss the next part of this McLaren Vale mini series when we’ll be exploring this hugely exciting renaissance

00:55:00

Peter: of the region, built largely around a new dimension in old vine, Grenache. Plus an intriguing supporting cast of alternative great varieties. Though of course, there’s more to the story than just that.

Susie: You do love to tease. Thanks to all our interviewees and also to the McLaren Vale wine region for sponsoring this miniseries. We’ll leave you with a different soundscape from Adelaide’s National Botanic Gardens. The sound of roosting flying fox bats. Google them if you dare.

00:55:31