- The John Malkovich EXCLUSIVE

- Marlborough Hits 50

- The Six BEST wine books

- Ventoux – Next Century Wines

- Ageing English Fizz: How, Why and What

- The Ten Wines Never to be Without

- The New Face of Languedoc

- Ukraine – Wine not War

- Our WINES OF THE YEAR (2023)

- A Southern French Feast

- ORANGE WINE Part 1

- ORANGE WINE Part 2

- Ancient Vines to the Rescue in St Mont

- Light Strike: Wine’s Not-So-Secret Scandal

- Grower Champagne with Lea & Sandeman

- Going Gaga for Garnacha

- SASSICAIA – The Insider’s Guide

- UK Wine’s Counterculture

- News & Views

- Rías Baixas – Mists, Myths, Mariscos

- Rías Baixas – Albariño with Attitude

- Red Wine Headaches: A Eureka Moment?

- Wine and War – Palestine, Israel and Lebanon

- We Need To Talk About Rosé

- Wines to Combat Climate Change

Summary

Deep in the wilds of south-west France there’s a vineyard that was planted over 200 years ago with unknown vines that may hold the secret to fighting climate change.

Join us as we head (virtually) out to Gascony to peer into the mists of wine history and see what lessons it holds for the future. Olivier Bourdet-Pees of the dynamic Plaimont cooperative is our genial, beret-wearing guide, introducing us to grape varieties we’ve never heard of and explaining how this region has been reinvigorated after making some of, ‘the worst wine in France 40 years ago’.

This episode is sponsored by AOC St Mont and features a number of wines including Plaimont’s iconic Vignes Préphylloxériques bottling (see below for more details).

Starring

- Olivier Bourdet-Pees, Plaimont

- Susie & Peter

Links

- You can find our podcast on all major audio players: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Amazon and beyond. If you’re on a mobile, the button below will redirect you automatically to this episode on an audio platform on your device. (If you’re on a PC or desktop, it will just return you to this page – in which case, get your phone out! Or find one of the above platforms on your browser.)

Wines

The following are wines we tasted in Feburary 2024.

Selected UK stockists are included – often with the best price available.

- Elia Liberty Cotes de Gascogne IGP, 9% (£8.50, Sainsbury’s)

- Plaimont Saint Mont Grande Cuvée Tradition 2020, 12.5% (£9.50, Tesco)

- Plaimont Saint-Mont Vignes Retrouvées 2021, 12% (£9.50, The Wine Society)

- Plaimont Saint Mont Projoe 2021, 13.5%

- Plaimont Le Faite Blanc Saint Mont 2019, 14% (£22, Corney & Barrow)

- Cirque Nord Saint Mont Grande Cuvee 2019, 14% (£39.50, Corney & Barrow)

- Fleurs de Lise Saint Mont rosé 2022, 12% (£8, Marks & Spencer)

- Le Manseng Noir, Planéte Cépages 2022 Cotes de Gascogne IGP, 11.9% (£10.95, The Wine Society)

- J’aurais dû être Tardif 2021, 13.5%

- Plaimont Vignes Préphylloxériques Saint Mont 2021, 14% (POA, Corney & Barrow)

- Les Hautains Pacherenc du Vic-Bilh 2021 Crouseilles, 12% (£10.50, Corks & Cru)

Get in Touch!

We love to hear from you.

You can send us an email. Or find us on social media (links on the footer below).

Or, better still, leave us a voice message via the magic of SpeakPipe:

Transcript

NB: This transcript was AI generated via Headliner. It’s not perfect.

In this episode, we’re traveling back in time through wine

Susie: Hello. You’re listening to Wine Blast with me, Susie, Barrie and my husband and fellow master of wine, Peter Richards. So welcome. and in this episode, we’re not only going to take you on a trip in terms of geography, we’re also going to be traveling back in time.

Peter: There we go. Time travel. I knew we’d get there in the end. You know, all this, this wine guff is really just a cover for our, top secret research into quantum physics. That and watching back to the future on repeat. We’ve got different roles here. This is a really exciting episode. I can’t wait to get started.

Susie: Yeah.

This episode explores how ancient grape varieties are being rescued against climate change

So, leaving quantum physics aside, in this episode, we’re going to travel to the remote reaches of southwest France, a land of wine that time forgot. In particular, we’re heading to the regions of Gascony and St Mont where one particularly ancient vineyard was planted before phylloxera in the 19th century, and which has been found to contain several wine grape varieties that are unknown to modern science.

Peter: Unknown.

Susie: Unknown.

Peter: Unknown as in alien?

Susie: Could be.

Peter: We’re going to X-Files territory here. M. I’m loving where this is going.

Susie: Alien vine.

Peter: I’m seeing it now.

Susie: I’m not sure that’s quite what we’re talking about here. more a case, I would say, of peering back into the depths of vine history, because we’re going to be exploring how these ancient grape varieties are being rescued from the brink of oblivion, all with the aim of helping the wine world fight back against climate change. Is it sounding Hollywood enough for you yet?

Peter: It really is, and it’s really working for me. Maybe just think about it. Maybe what is more Frolywood than Hollywood? As opposed to Bollywood, maybe.

Susie: No, the good news is, beyond the Frolywoods, this is also helping socially and in terms of sustainability, more widely. So it’s all part of a really fascinating story. And this story is focused around the Plaimont cooperative, one of the biggest such producers in France, and certainly one of, if not the most forward thinking, innovative and dynamic co ops in the country. and Plaimont is working to preserve and promote the historic diversity of grape varieties in a part of the country which they themselves admit made some of, and I quote, the worst wine in France 40 years ago.

Peter: It’s quite something to hold your hands up to, isn’t it?

Susie: at least they’re admitting it.

Peter: No, exactly. It’s fair enough. I can’t really like that.

Susie: They’re very honest.

Peter: Very honest. And what I’m seeing here, if we’re framing it in the Hollywood Follywood sort of context. It’s a sort of plucky, fight back sort of story. I love those stories, but my problem with them is they rarely involve enough wine.

Susie: Oh, this one will.

Peter: So I think we’re going to solve both.

Susie: Blockbuster with booze. Anyway, here’s a small taster, of what’s to come.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Southwest France is around 10% of the french production in wine, but it’s nearly 40% to 45% of the biodiversity in grapes. We had this incredible potential in diversity. The region was nearly dead. right now we are alive. The potential of Gascony is really, really special. Maybe one of the regions of the future.

Susie: So lots to explore now, that was Olivier Bourdet Pees from Plaimont and we’ll be hearing more from him in due course. Ah, we’ll also be tasting a fair few intriguing wines that help tell the story. And we should say from the outset, many thanks to the AOC St Mont for sponsoring this podcast and allowing us to turn our attention to such an intriguing tale indeed.

Wine growing culture dates back centuries in southwest France

Peter: so I think we probably need to sort of set the scene a bit, don’t we, to know where are we? What are we talking about?

Susie: Sure. Okay, so we’re in southwest France. We’re between Bordeaux and the Pyrenees mountains inland from the Atlantic Ocean. In terms of landscape, we’re talking verdant rolling hills and fields. And there’s a fair bit of rain here, too. They play rugby, they occasionally wear berets. Bit of a link with the Basque country over in the Pyrenees. And they love their food. Duck and foie gras are two very famous local products.

Peter: I’m just wondering if these three things go together. I’m not sure they necessarily do, but maybe one thing that makes them is the love of wine. Love of wine, I think particularly drinking wine and Beret wearing. I wonder if those two go hand in hand afterwards. But, anyway, the local wine growing culture dates back centuries in this part of the world, at least as far back as the Romans. then developed by religious communities and monasteries, partly to serve the tide of pilgrims. on the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route, which, passes through here into northern Spain, of course.

Susie: Yeah, but that was a while ago. And as pilgrimage highways faded in importance, this area fell off the beaten track. It was also given the cold shoulder by Bordeaux, which was the dominant regional commercial hub and port. The Bordeaux merchants wanted to prioritize their own wine, rather than the wines from upcountry as they saw them. so they restricted access for other regions to the port. Yeah.

Peter: and all this meant these areas in southwest France retained a traditional culture. They didn’t race to modernize. They kept a fabric of small holdings, often polycultures, producing everything from livestock to fruit and veg and wines. this process inadvertently ensured the retention of local wine grapes. It’s estimated that there are 300 different grape varieties in this part of the world, of which 120 are indigenous.

Susie: Can you even name that many grape varieties? I mean, I couldn’t. It’s quite a.

Peter: Actually, think about, you know, I get stuck after Chardonnay. That’s because you drink too wet. I get stuck in more ways than one. This is very true. Anyway, let’s move on. now, this is also the land of Armagnac the famous french brandy. but there came a time in the 1970s when as delightfully rural a bucolic as life in this part of the world was, local producers were facing ruin. Prices for grapes and wine were rock bottom, partly because the wines were pretty dodgy back then, exactly as you’ve said. so things were looking pretty grim.

Susie: They were. But then along came Andre Dubosc ah, a third generation wine grower. Now, he saw the scale of the problem and he encouraged local growers to choose a side. So we are looking a bit more rugby now, aren’t we? scrum, dad. Anyway, those two sides were armaniac or wine, but not both. He then helped set up the Plaimont Union of cooperatives in 1979. a, cooperative being a winery sort of jointly owned by shareholding farmers or grape growers, who come together and pool resources to make and to sell their wine. And Monsieur Dubosc encouraged not only pride in the local grapes and wines, but also galvanized the local producers to be ambitious and open minded.

Peter: So Plaimont has about 800 winemaking families. It’s not bad. And its collective vineyard covers around 5300. Ha. So this is big.

Susie: This is big.

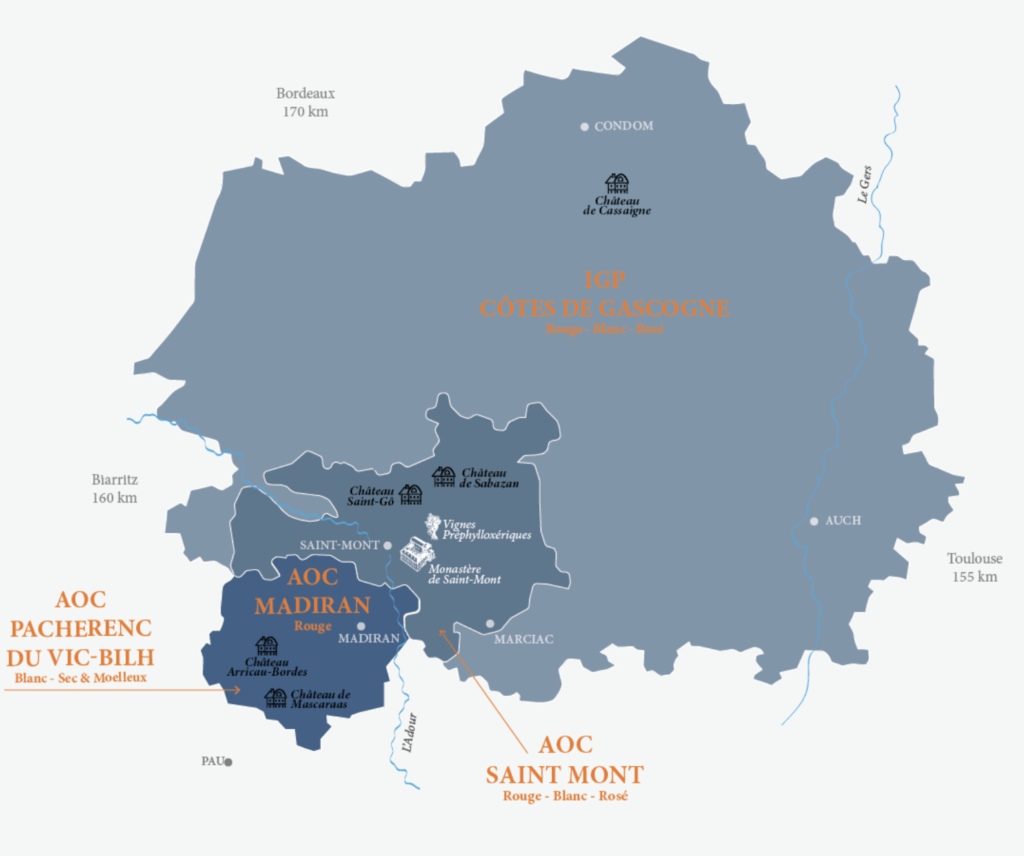

Peter: it produces wine from all over the region. But its heartland is the AOC, the appellation Saint Mont, mmont, which lies within the broader Cotes de Gascogne area and is a kind of extension of the Madiran appellation in terms of geography, we’re talking north of Pau and directly west of Tulouse, in the foothills of the Pyrenees.

Susie: Yeah. So here the specialities in terms of wines are fresh whites and sturdy kind of punchy reds.

Peter: We’ve got some of these right here in front of us, positively winking at us.

Susie: Old your horses. now, before we come on to the wines. So we’ve painted a picture of this region, but I do think we should hear it from the horse’s mouth, as it were. so Olivier Bourdet Pees is a trained winemaker and CEO of Plaimont He’s a man who wears a beret very well.

Peter: That’s true.

Susie: Worth a google, isn’t it? We might put a couple of pictures on our site. Anyway, I asked him to give us a brief overview of the region.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Many, many people do know about south of France, but there is a small part of south of France, which is the foothills of the Pyrenees, where the influence, the climatic influence of the atlantic ocean and of the Pyrenees make this region really rainy, really fresh, with the climate totally different, with the other parts of south of France, that makes this particular, viticulture with traditional grapes coming from that zone, original ones. the main part, 95% of the wine growers here are using only grapes born in that region. and this is the big particular because of the climate, because of the chooses of the wine growers here in the regions. we did that job, which is really unique, maybe in France, different, kind of grapes to explain this wonderful terroir.

What about the food and the culture in the southwest region of France

Susie: And just before we talk about the grapes, what about the food and the culture in the region?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Yeah, culture. Maybe southwest is a bit more known for this because I think, it’s a region where living there, is a privilege, maybe a region a bit away from the beaten tracks that make, maybe in gascony much more than in other regions. The ability to live in a quiet moment with the families, with the friends. It’s a really particular region for that. And then, the quality of the food, the quality of the wines is really very, well known. And, maybe gascony is much more known for the duck, I don’t know, for the cheeses, for the Pyrenees and many, many things for the black pig, very wonderful black pig, in the region. So, yeah, the quality, the living quality is really unique.

Susie: And why would you say history is important in this part of the wine world?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Yeah, again, history, maybe the main part is, again, in history being close to the spanish countries, being, close to the Pyrenees, far away from everything, I would say, there is no motorway in our region, for example. now, that made a specific way of thinking, the way of living. people were there, polyculture was the tradition there. they were eating what they were producing. So, they didn’t make the choices, made everywhere else in the world. They did their own life, a, ah, way of seeing life and their own shoes, on making their products for food or for wine, for example.

Peter: No motorway. it sounds both idyllic and a bit slow. Frustrating. I love the emphasis on food and wine and living well.

Susie: And you notice Olivier talks about the mentality and choices people make, including retaining their local grape.

Peter: Yeah, so this is where it gets really interesting, doesn’t it? And you definitely asked him a bit more about that.

Susie: Yeah, I did. So here’s what he said when I asked him to tell me a bit more about these magical grapes.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Southwest France is around 10% of the french production in wine, but it’s nearly 40% to 45% of the biodiversity, in grapes. we had this incredible potential in diversity with the traditional grapes coming from the footiers of the Pyrenees. A lot of regions lost their traditions, but here in the southwest, we kept those traditions and we are still, working with our own grapes. Each appellation in the region is using its own grapes. That makes maybe sometimes a bit complexity, I would say, for sure. But the potential, the huge diversity we have to face, the willing of the society to have different kind of wines, the ability to adapt to the climatic changes, is huge. When you have those tools, those grapes are the tools able to answer the big, big challenges we have to face.

Susie: I mean, you work with some really historic grape varieties, don’t you? So can you tell us about those which are the most historic? What do they taste like? How easy are they to work with?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: In Plaimont in my company, we have the most important conservatory, private, conservatory in France. we have in Plaimont 39 disappeared grapes completely, disappeared. and they were disappeared because the willing of the wine growers one century, two centuries or five centuries ago was to stop with them because they were not adapt to the willing of the moment.

Susie: Is that in terms of flavor or in terms of their productivity or what was it?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: for example, Susie? I don’t know. If you taste the Manseng noir, for example, the wine Manseng noir, the Manseng Noir is, a grape really close to Tanat. But the ability of Manseng Noir to produce sugar is much, lower than tana, for example. So when the climate was so fresh, it was so difficult two centuries ago to, get the perfect maturity, to get the level of alcohol they were, focused on, in this moment, they stopped with monsanoir and, everyone went to the tanat, with at least two to three degrees more, in potential, in alcohol potential right now, if the situation is changing a little bit with the climatic changes, with the willing of the society and our customers, maybe, monsignois is the big answer. Natural answer present on the territory, really close root and linked to this territory. But able to answer, what people are waiting, right now, they want more freshness, they want less alcohol, they want more drinkability. Maybe in the wines, they are not always able to wait for ten years in a bottle to have the perfect wine. So Manseng Noir is really one of the answer for the future. It’s an example. We have many of them. Maybe we had, very late grape that it was impossible to get the maturity, the tanic maturity, the phenolic maturity in those grapes because they were picked, I don’t know, again, two centuries ago, end, of November, or middle of November, it was impossible to wait that time. So they stopped with that grape. But maybe again, with the evolution of the temperature, this grape right now is able to be picked at middle of October or beginning of October, which is huge for us to have this kind of possibilities.

Susie: and do you have yourself kind of a favorite, one of the revived grapes or one with a particular story?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: All of them, are my sons. It’s impossible to choose. But yeah, I will tell you, I have maybe, Manseng Noir is one tardif. tardif in French means late. You can imagine that the wine grower, three or four centuries ago that gave this name to this grape. I’m not sure he was in love with it. It was late. Tardif was not good for him. But maybe it may be a privilege to have a very late grape, in those moments, able to have a long log, slow maturity with the ambition of the wine growers right now. So, yeah, Tardif is incredible. it’s, driven by an aromatic expression, very spicy, given by a molecule that the name of that molecule is rotundone It’s black, pepper, green pepper. the complexity is huge. It’s so easy to drink, really aromatically. maybe it’s my favorite. Tardif is really something incredible. And then, we have sounds that are not so easy, sound that is not perfect by itself. But maybe when you use it in a blend, it can bring something very incredible. But I would think about arifiac, which is maybe a tanic, a bit of white grape by itself. Maybe it’s not wonderful. But, the drink ability, small bitterness it gives to the end in the mouse when you have too much sun, when the mouse is a bit fat. It’s wonderful to think about that kind of grapes to help the blends.

Peter: So I’m still trying to get my head around the fact that they have a conservatory with 39 grapes that previously had disappeared off the landscape into viticultural nirvana, which now they’ve rescued and are bringing sort of back from oblivion.

Susie: Yeah. So this is a big part of what they’re doing. Hugely valuable work, not just historical and cultural value, but also this is something that’s proving incredibly useful in the fight against climate change. As Olivier said, varieties that were too late ripening in the past are now coming into their own because growers want less sugar and ripeness in their grapes, because otherwise alcohol levels are too high, in this ever warming climate. Yeah.

Peter: And it’s not just about heat, is it? But coping with other things, too, like drought or frost or hail or rot or other kinds of pests and diseases which, are coming into play because climate change is shifting the goalpost in terms of local conditions for all those things.

Susie: And who knows what more resources we’ll need in the future to perhaps even adapt further. Anyway, let’s go from theory to practical, shall we? Because Olivier talked about a couple of grape varieties and wines which we’ve got here to taste.

Peter: Now you’re talking my language. We’re calling it a practical these days are brilliant. Fantastic. Okay, whatever we’re calling it.

Two cheeky white blends featuring arufiac grape give pleasant bitterness

first up, we’ve got a couple of, cheeky white blends featuring the, Arrufiac grape that Olivier mentioned as giving sort of that lovely, pleasant, gentle bitterness to a white. I often think when you talk about bitterness, it sounds bad, doesn’t it? But actually, in wine, it can just a little bit can be.

Susie: But just like that sort of pithy.

Peter: Zestiness grounds a wine, especially a wine wine. So the first one is the, Plaimont St Mont grand Cuvee tradition 2020. It’s a blend of gromo, sang puti, corbu and Arrufiac As you said, it’s about nine pounds 50 at Tesco. And it’s gorgeous.

Susie: Yeah, it just does that classic trick of the best southwest french whites. It manages to be fresh, really fresh and cleansing and juicy. But it’s also complex and quite broad. It’s got flavors of. There’s some honey there, some stone fruit, a bit of red apple, dried herbs, I think. So much wine for your money. I actually remember pairing wines like this on Saturday. Kitchen and they were a gift in terms of food and wine matching, because they just went with everything. So amazing. Amazing value too.

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. it’s not your average supermarket white, is it? Maybe a good alternative to Alberino or pinot grigio, whatever you sort of tend to drink. Or chablis or sancer even, I think.

Susie: Definitely chablis. Yeah.

Peter: Okay. Good alternative there. But anyway, we’ve got another one here. It’s the Plaimont St Mont vinya retruve 2021. It’s, the same blend. It’s gramon sang puti corbu arufiax. Nine pounds 50. Same sort of price at the wine society this time. And it tastes sort of like a younger, slightly greedy version of the grand Cuvee doesn’t it?

Susie: Yeah, I mean, it’s nice, it’s Zesty, and as you say, that slightly younger taste, crisper taste with a touch of white pepper on the finish. So, yeah, thumbs up to white blend, starring Arufiak.

Peter: Yeah, I think generally the whites in this part of the world are really exciting.

Susie: Yeah, you’re right.

Peter: Interesting, great varieties. Arufia being one too.

Susie: Different.

Now we got a couple of reds. One is quite low alcohol, 11.9%

Peter: Now we got a couple of reds. first up is the monseign noir planet sepage 2022. Cooked Gascogne igP. It’s about eleven pounds at the wine society. Again, so not expensive. as Olivier said, it’s quite low alcohol. It’s 11.9%. You, look at it, it’s really dark in color, but it’s really kind of upbeat and sprightly in taste, isn’t it? Sort of aromatic and very tangy and lively on the parrot, sort of lovely, bright, refreshing style of red.

Susie: I mean, I really like this, as you said, very dark, meaty. Got some floral notes, but some nice chalky tannin. I love the fact it’s lower alcohol because it doesn’t lack on character, because it’s lower alcohol, which is quite rare. You’ve got character, you’ve got flavor.

Peter: Yes. It can happen, can’t it? Can just be lean and m boring.

Susie: Absolutely. And this is not at all. And it’s lovely and refreshing with food. It’s uplifting. So you’ve got maybe a plate of cold meat or even, I don’t know, spag bowl or something, just something simple.

Peter: And also, I think it’s a style that’s really quite fun and a little bit, I don’t know, bit quirky, maybe. I think there’s a lot they can do with this kind of style of winemaking. Making styles that are just fun. in the reds, I think it’s really, really good. Anyway, now we’ve got a wine from the, famous, or perhaps infamous Tardif variety, as Olivier was talking about, which apparently does not exist in the record books, by the way, I did check.

Susie: I bet you did.

Peter: I did check, and I couldn’t find any reference. Monstein noir does. but not Tardif. so we literally are tasting the unknown here. that point nonexistent, made pretty clear by the picture of the dodo on the label, which is really quite a nice touch. This is actually a van de France, because, again, I think it’s sort of experimental one, but it’s nice. And it’s called the Jorge du etra Tardif 2021.

Susie: Yeah, it’s pretty punchy, isn’t it? M. I’m going to be honest, I’m not sure it’s my favorite. It’s pretty full on in terms of tannins. you’ve got a lot of black fruit intensity, but it’s also quite rustic. It did go okay with a pulled pork chili that we made, but, I think it’s a work in progress. It’s got potential, but I’d still go with the monseigne noir at the moment.

Peter: Yeah, I tend to agree. I mean, they might tinker with how they make it and whatnot, but anyway, I definitely stick with the monseignoir or the whites, actually. again, all made with local varieties, something a bit different. And, yeah, I do think the Tardif is a project they’re still working on rather than a big commercial release. For now, anyway, we’re going to talk a bit more about Tardif and ancient pre phylloxera vineyards in a bit, together with more tasting and how all of this is shaping a unique future for St Mont and southwest France. To recap, so far, southwest France is not only full of hearty food and beautiful pyrenee and landscapes, it’s also a treasure trove of ancient grape varieties which are now being repurposed in the fight against climate change. So we might be hearing a little bit more about grapes like Arrufiac and monseignoir and Tardif in the future.

Susie: Indeed. Now, as far as I understand it, Tardif, whether it exists or not, was actually one of the unknown varieties that was discovered in a vineyard in St Mont that’s over 200 years old and which has managed to survive everything from phylloxera to the relentless march of modernity.

So I wanted to ask Olivier about these ancient vineyards in France

So I wanted to ask Olivier about these ancient vineyards. two in particular stand out. One is a national monument in a place called Saragashi, owned by the Peda Bernard family, which was planted in the early 18 hundreds where they found these lost varieties. That one doesn’t make a bottled commercial wine. But then there’s another one which they do make a wine from, which we tried, and which we will come on to after this.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: So in St Mont appellation, which is maybe the first main appellation, in plemon zon and one of the most famous, appellation in the foothills, of the Pyrenees, we have two different preferoxeric vineyard. The one you were talking about, was, planted under Napoleon first very, beginning of the 19th century. It is more than 200 years old right now. And, the last thing of that incredible plot is that it’s a very small one. And you have 21 different, grapes. All of them are disappeared. sometimes we don’t know even their name. and seven of them, we don’t know anything about them. And some of them are so ancient that they are female. They are not hermaphrodit grapes. They don’t have on the same plant, the male and the female, flower. So, it’s very, protected. It’s an incredible plot, really.

Susie: and it’s still producing enough yield.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: To make wine from wine, in experimentation, not a bottle, I would say, in that plot, because you have two, three, four plants of each different, grapes. So it’s difficult. But we are, resisted with the average production, we have. It’s incredible why this plot, gave us this, incredible diversity. It’s unique. Unique. And it’s unique in France. It is the only one recognized, as the monument, historical monument in France. Right now, it was, recognized in the year 2011 and it is still the only one. And there is another one, maybe you tasted, again, the wine there is the youngest, prefiloxeric, wine, in St Mont It’s, a plot planted in the year 1871. So not so young. so no root stock at all planted on Tanat, only tannat. And in that plot, alpha nectar, we are producing a wine. And it’s a bit the roof of our, production. It’s really something incredible to see, the potential of the wines, when you are working with material, no selection, at all. The diversity inside the plot is unique. So that gives a complexity to the wine that is really huge.

Susie: And that’s your top wine.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: You would say, yeah, it is. Well, at the end, I am in love with that, Cuvee I don’t know if I am right, but when you are facing this, you are facing the work of six, seven, eight generations of wine growers, maybe more, seven to eight, that kept this potential. They didn’t sell any wine for more than one century. It was only for their own consumption. they were protecting this. They are giving that plot and that unique plot to their sons. And the son walked, with it during 30, 40 years, and it gave this to his own son or daughter. And, without earning any money, only by conviction. they were linked to, this small garden. And I arrived ten years ago and I saw this. It was, 15 years ago now, and I saw this history, this potential, this willing of generations and generation. And when you are facing the wine, it’s really a privilege, something very special to walk. This blood, for me, is unique. And I am pretty sure that if you are, lucky enough to have the wine in front of you, it’s an emotion that is very specific.

Peter: Well, we can talk about that emotion now, because we have this amazing one off wine in front of us in our glasses. but before we come on to that, it is quite some thought, isn’t it?

Researchers are studying ancient vines to help make modern wine knowledge more progressive

tasting the fruit of vines that are over 150 years old. The sort of work, it’s not really work, is, it’s more passionate. It’s more sort of just the treasure of generations. I know what he means. It sort of sends a shiver down your spine, doesn’t it?

Susie: Yeah, totally. But just to shift focus for a moment to the other, the older vineyard he talked about, the one planted in the early 18 hundreds. So, as Olivier said, they have seven vine varieties there that they just can’t identify. And, as he said, some are female, not hermaphrodite. So just putting that into context, all modern winemaking vines are hermaphrodite because it means they produce fruit more reliably and abundantly. You don’t have to fertilize the flowers for them to become baby grapes.

Peter: That’s almost a glimpse of sort of prehistory, of humanity as well as for winemaking, isn’t it? You’re almost going back to the Near east and Caucasus region and seeing these sort of early civilizations bringing wild vines out of the forest, where they would have been growing up the trees and then domesticating them, planting them out. And of course, they would be choosing the hermaphrodite mines, because those ones gave the best yields. So it’s a sort of crazy thought. We’re peering into this prehistory, sort of. Ah.

Susie: And although, as Olivier said, they’re not making wine from that oldest plot because it’s too small, they are doing lots of research, and that’s something they really focus on there, doing the research, studying these ancient vines to see what we can learn, how they can help make modern wine knowledge and what they’re doing with the wines today more progressive.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: yeah.

Southern French wine from prefiloxera vineyard from 1871

Peter: And talking of wine today, back to our glasses.

Susie: Oh, here we go.

Peter: Let’s taste. We’ve got the very special vineyard, prefiloxeric St Mont 2021. It’s from this ancient prefiloxera vineyard planted in 1871 in St Mont that Olivier described. It’s 00:40 8 under half a hectare of ungrafted tannet. there are a few other bits and bobs in there, but I think they don’t use them in this wine. it’s a beautiful bottle. What do we make of the wine?

Susie: Well, it is very special, isn’t it? it feels like there’s almost a universe in this wine. You can kind of almost taste the history. It’s like a time machine in itself, isn’t it? But nuts and bolts. It’s got a beautiful fragrance. Lots of dark fruit with floral and herbal hints. Very southern French, but you get this very fine textured, quite sort of linear palate profile. Very pure, with juicy, dark fruit acidity and then some chalky tannin. A little bit of spice. I mean, it’s quite upright and sturdy, but also very layered and complex. There’s just tons going on. Not for the faint hearted.

Peter: Sort of puts hairs in your chest, doesn’t it?

Susie: In a good way.

Peter: In a good way. Really good way, yeah. I like your description. It sort of captures the essence of red wines from the region. Does it?

Susie: Really does.

Peter: M there’s a real sort of intensity there, a sort of uncompromising energy and vigor. It’s bold. I think that’s a word I’d associate with a lot of the reds from here. Touch of rusticity. Yes, I’d say it’s really quite young, intense, isn’t it?

Susie: it is, but it drinks well, doesn’t it?

Peter: It drinks really well. And I think that it’s that fresh fruit, ironically, in there, actually, that’s helping it drink really well. It helps it balance out the tannin, the acidity. and I think, actually, I would recommend drinking this wine, even though it’s very pretty intense, relatively young to retain so you get that fresh fruit in there, don’t stick it away for ages. You called it, upright or something like that, didn’t you? And I think that’s a good description. It’s quite an intellectual style. It sort of makes you think, doesn’t it? You get the finesse as well as the power. And definitely another one for food.

Susie: Definitely. I mean, I was thinking about this and I reckon that duck shepherd’s pie we made a few episodes back in our southern french feast programme would be really good with this. So that’s quite a special wine. But I also wanted to ask Olivier about other aspects of what Playmont does. Things like the cheaper end of the spectrum, coked gascon whites, the bread and butter stuff, if you like. So here’s what he had to say about good value gascony wines, among other things.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Well, the price for regionality, I would say is because that region was not so recognized. It was nearly dead 40 years ago, to be honest, this region, was living with maybe alcohol production, mainly. Many more harmoniac production. And when armaniac production, has its own difficulty, 50, 60, 70 years ago, yeah, the region was nearly dead. right now we are live, proud to be able to present those incredible products. yeah, the potential of gascony is really special. And at the, end, maybe the climatic evolution is coming to us. We were too fresh, 100 years ago, 50 years ago to have the good balance, the good, potential, to be recognized as a top, top region in the world, for wine production. But more and more, those regions are, ah, maybe one of the regions of the future. So, yeah, I am m proud to be still, being, a, wonderful price, and, originality and price, value. And I’m pretty sure that more and more people are looking for our wines, looking, for that kind of experience when you are drinking, I don’t know, 100, Chardonnay a year or it’s still a good moment to discover something really new, italian, people were, wonderful to keep that and to give value to that. We are trying to do, with the same ambition. And, Yeah. Ah, lucky are the people who are able to discover our wines. I’m not talking about Playmont, but the wines of the region. If you are going to Madiran, to Pashrang, to Juronson, to Iruulegi in the pebasque, you will find wonderful wines, affordable wines, at the end, but with an incredible potential to make you travel.

What are you doing as a cooperative to be sustainable. What is changing in terms of winemaking as well as grape varieties

Susie: What are you doing as a cooperative to be sustainable.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: I don’t know, if you are looking for this, but in this moment, in France, all the agricultures are a bit, in difficulties. They are a bit fighting, in the road because, they are on strike because, many of them are suffering. So giving them back the money, we are able to bring back to the territory is something very important, for sure. and then, to be able to do that, we have to have an interest in the production we are giving to the people who are believing in us. And for this, we have to improve the way we are producing the grape. In term of, quality, of the grapes, diversity of the grapes, on the ability to make each wonderful project able to exist. we are not a co op where we want to blend big tanks. if we have to produce a, wine coming from alpha, nectar coming from a preference Eric vineyard with a unique wine grower, incredible wine grower in that plot, we have to do that. and we will produce 1000 bottle a year of that plot. That makes the possibility for a customer to be interested in, what is happening in our region. And then we will try to sell him, to share with him another Cuvee or another history with the plot in front of that one. But we have to do everything in the quality of the history and the roots of what we want to be. And then, for sure to improve the way we are producing the grape. having less, problems for our territory with pesticides, with the co2, pollution in what we are. Everything is, adapted in Plaimont to improve days after days. We are not perfect, but days after days the project is to improve. We don’t have all the answers for everything, but we are looking for them in each part of our production.

Susie: And just looking at winemaking in general, how it’s changed over the years in your part of the world. I mean, particularly visa vis. There’s a sort of very powerful reds that the region is known for. You talked earlier about the grape varieties that are allowing you some more freshness and lift and perhaps lighter alcohol. What is changing in terms of winemaking as well as grape varieties?

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Everything. We don’t want to think about a curative way of, facing the problems. You have to change many, many things. You have to be able to adapt to the moment. Technology is never an never. To answer your question. Very good question, for sure. In Plaimont the potential in diversity of the grapes is one of the answers. One of the answers, then maybe adapting, the exposition, we are pure south. All the plots with southern exposition, with big slopes like this, that were capting a lot of energy from the sun. Where do. The answer, was the answer of 50 years ago, to catch this perfect maturity we were looking for right now, maybe when you are focusing the freshness and the balance, maybe those slopes won’t be the answers for the future. So you have to adapt to put away your plot. You booked this plot, very expensive price, because it was the best in the region. And maybe it’s the worst for the next century. I don’t know. maybe you have to say, okay, it’s adaptation. And then for sure, in the winery, you have to adapt. extraction in the region was something very important. We had wonderful means to extract everything we had in the skin. We wanted to catch, in the skin. Everything, all the tennins, all the aromas, all the color, everything was catched by extraction. and maybe we are balancing this, right now much more with infusion. the grape is in the tank. And the way we are extracting the grape has completely changed because we don’t want that kind of wines. We don’t drink those kind of wines anymore, ourselves. So, we are adapting with more eliquency in the wine and more eliquency in the way we are thinking our, winemaking.

Susie: Olivier, thank you so much.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: Thank you. It’s a pleasure.

Peter: So they’re adapting their methods, planting in cooler sites, given global warming, extracting their reds less so, less tannin and power. Aiming more and more for elegance, like we saw in that monseigne noir. Sort of juicy and upbeat and coffable style, rather than tannic and chewy and alcoholic and hard work, which has been a valid criticism of many of the reds from this region.

Susie: Yeah, absolutely. But they’re moving with the times. I think that’s key. Just as Olivier said, they move from armigniac production to wine production, focusing on what makes them unique, making wines that are a bit different. a discovery almost. And that’s sustainability in action.

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, he said the region was dead and now it’s alive. So clearly they’re doing the right thing, focusing on good value at one end, but also then on really unique, small production wines at the other to communicate that sort of identity and uniqueness. and I think, as I said, there are opportunities to do really quirky things, too, especially with these new old varieties in the red wine spectrum. Do something fun, funky, natural, something just juicy and I don’t know.

You also mentioned affordability, which I wanted to pick up on

Susie: Yeah, and you also mentioned affordability, which I wanted to pick up on. And I think this is a really important point. Generally speaking, these wines are really good value. They’ve got absolutely, lot of character, and the price tags are incredible in that context.

Peter: Totally agree.

Susie: I would say, however alive it is, this is partly because the region still isn’t very well known.

Peter: Yeah, totally agree. You can definitely pick up a bargain from here. Whites, and reds, but particularly whites, I’d say. they can age and develop well. They can become really quite complex, but rarely at silly prices. That grand Cuvee under ten quid is delicious, isn’t it?

Susie: Yeah.

Peter: You compare that to other regions mentioning no names. Burgundy.

A couple of slightly more expensive whites, uh, but still amazing value

Anyway, I think on that note, we wanted to feature a couple of, final bottles today.

Susie: We did, yeah. So a couple of slightly more expensive whites, but still amazing value. The first up is the La Faite blanc St Mont 2019, which is 22 pounds. It’s a blend of groman seng, pity monseng and putti kobu. Really complex and rich. Tons of waxy, buttery, nutty, yeasty dried apricot fruits. Quite fleshy and spicy, but with tangy acidity underneath it all. you got that touch of age there, which is nice of 2019 vintage. Just very multidimensional and with lovely texture, lovely character, and a very fair price, I think. And good with food.

Peter: I mean, it’s not cheap, but I think it’s a very fair price. You get so much wine.

Susie: You do.

Peter: I was also seriously impressed, talking rich by the Cirque Nord St Mont Grand Cuvee 2019. now, this is 40 pounds at corny and Barry, so it’s more expensive. One’s twice the price, but it’s a treat. It’s a more flinty style. Again, really complex and intense, but perhaps a bit more focus and sort of drive and cogency than the lafette, which you’d expect, of course. there’s sort of hints of curry leaf, of roasted hazelnuts and red apples. It’s really broad, but also dense and tangy on the palate. It’s big, but it’s very serious and balanced and that lovely, typical refreshing acidity underneath it. There’s so much going on there. It’s sort of like a freight train hurtling along your palate. It’s pretty thrilling stuff.

Susie: sounds like it. Anyway, I wanted to perhaps move to something slightly less thrilling but different. Just a bit different. This is the Elia Cotes de Gascogne IgP. Much, less expensive, about eight pounds 50 at Sainsbury’s. it’s made from Columbard and sauvignon blanc, and it’s only 9% alcohol. Now, it’s made specifically to be in that lower alcohol category, harvested early. And, then the fermentation is stopped before the end, so you get that bit of succulent sweetness to offset the tangy acidity. And it works well.

Olivier Bourdet-Pees: It really does.

Susie: Zesty, off, dry, upbeat, perhaps for lightly spicy food, I would say it’s a great shout.

Peter: Yeah, absolutely. now, I’ve got a couple of others here. The Playmont St Mont Projo 2021. It’s a bit different in that it’s quite a sort of creamy, leezy style of white. I think there’s a bit of oak there, which is not all. These wines do have a lot of oak, but it’s a bit more generous. It works well to kind of put flesh around that fresh acidity. and then also a rose, the fleur de lis St Mont Rose 2022. I think it’s really nice. It’s sort of elegant, but with good character. And we want a bit of character in our rose these days, don’t we? Yeah. And I also think good point to make here is that Rose is a really good option for some of these local red grapes. Actually, this, one’s a blend of pinank, which is the name for fair Salvadou and cabernet sauvignon. And I think you can make some really juicy, fun, characterful stars. absolutely. Rose, as opposed to big, hefty reds, which is really interesting. This one’s only eight quid.

Susie: Yeah. Bargain, bargain. And finally, we’ve got a sweet wine. The Lezoten Pashran du vic Bill 2021. it’s organic, just over ten pounds for a half bottle. And it’s just a really lovely, sweet, but not overly sweet style. Not nearly as rich and heady as Sauterne would be. It’s very attractive. It’s got lovely orangey citrus fruits. and again, ten pounds for half bottle of a nice, sweet wine. It’s good value.

Peter: So there we have it. we did our time travel and we’ve come out the other side having not disrupted the spacetime fabric too much, I don’t think. I guess time will tell. We don’t know, but I’ve got no.

Susie: Idea what you’re talking about.

Peter: Maybe there’s just a little bit less wine out there in the space time fabric than there was before, but that does tend to be the result of our.

Susie: Possibly. Possibly, and yes. By way of brief closing summary, southwest France is making arguably the most exciting wines in its long and checkered history. These are wines made from characterful local grape varieties, some of whose origins are lost in the mists of time, but which are being repurposed for the modern era and at the same time, helping growers adapt to climate change. Gascony St Mont and the Plaimont cooperative are at the heart of these intriguing developments, including working with their ancient prefaloxera vineyards and rescuing vine varieties from the verge of extinction. The best wines represent outstanding value for money and, are brimming with character.

Peter: So well worth discovering. thanks to Olivier Borde Pees also to AOC Saint Moore for sponsoring this episode. thanks also to you for listening. Until next time, cheers.