- The John Malkovich EXCLUSIVE

- Marlborough Hits 50

- The Six BEST wine books

- Ventoux – Next Century Wines

- Ageing English Fizz: How, Why and What

- The Ten Wines Never to be Without

- The New Face of Languedoc

- Ukraine – Wine not War

- Our WINES OF THE YEAR (2023)

- A Southern French Feast

- ORANGE WINE Part 1

- ORANGE WINE Part 2

- Ancient Vines to the Rescue in St Mont

- Light Strike: Wine’s Not-So-Secret Scandal

- Grower Champagne with Lea & Sandeman

- Going Gaga for Garnacha

- SASSICAIA – The Insider’s Guide

- UK Wine’s Counterculture

- News & Views

- Rías Baixas – Mists, Myths, Mariscos

- Rías Baixas – Albariño with Attitude

- Red Wine Headaches: A Eureka Moment?

- Wine and War – Palestine, Israel and Lebanon

- We Need To Talk About Rosé

- Wines to Combat Climate Change

Summary

What do bagpipes, rain, witches, pilgrimage, lampreys and Albariño all have in common?

Not much really – but they are all featured in this episode on Rías Baixas, the intriguing wine region in north-west Spain famous for its seafood, verdant landscapes and refreshing, brine-tinged white wines.

Historically, this was always a remote region of hardy fishermen and misty hillsides. But since the 1980s a wine revolution has been taking place, majoring on a distinctive style of Albariño we wine drinkers have lapped up, and propelling the official appellation vineyard from a tiny 237 hectares in 1987 to 4,480 hectares today.

In this first instalment of a sponsored two-parter with DO Rías Baixas, we get a feel for the place, its people, history, food and wines.

We explore the region’s famous whites, recommending some as we go, but also explore the lesser known reds and sparkling wines.

Peter has a run-in with a sea urchin and a particularly pungent lamprey stew, and we hear from Stephanie Schilling (Santiago Ruiz), Susana Pérez (Pazo San Mauro), Fernando Oubiña (Mariscos Laureano), Natalia Rodríguez (Señorío de Rubiós), and Lúcia Barbosa (Adegas Galegas).

Starring

- Stefanie Schilling (Santiago Ruiz)

- Romina López

- Susana Pérez (Pazo San Mauro)

- Fernando Oubiña (Mariscos Laureano)

- Natalia Rodríguez (Señorío de Rubiós)

- Lúcia Barbosa (Adegas Galegas)

- Susie & Peter

Wines

The following are Rías Baixas wines we tasted in April/May 2024.

Click on the wine name for the Wine Searcher link to find where you can buy this wine around the world.

- Galegas Pazo de Almuíña Veigadares Branco de Brancos 2021, 12.5%

- Adegas Valmiñor Davila M-100 2018, 12.5%

- Señorío de Rubiós Mencia 2023, 12%

- Señorío de Rubiós Espadeiro 2016, 12%

- Attis Pedral 2019, Tinto Atlántico, 12%

- Attis Caiño Tinto 2018, Tinto Atlántico, 12%

- Attis Espadeiro 2018, Tinto Atlántico, 12%

- Galegas Danza Espumoso de Albariño Brut

Links

- You can find our podcast on all major audio players: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google, Amazon, YouTube and beyond. If you’re on a mobile, the button below will redirect you automatically to this episode on an audio platform on your device. (If you’re on a PC or desktop, it will just return you to this page – in which case, get your phone out! Or find one of the above platforms on your browser.)

Get in Touch!

We love to hear from you.

You can send us an email. Or find us on social media (links on the footer below).

Or, better still, leave us a voice message via the magic of SpeakPipe:

Sponsorship

This episode is sponsored by DO Rías Baixas using EU funds.

Transcript

This transcript was AI generated. It’s not perfect.

Susie: Hello and welcome to Wine Blast. I’m Susie Barrie and I’m here, as ever, with my husband and fellow master of wine, Peter Richards. What’s not so normal is our intro music…

Peter: Yeah, no need to adjust your sets. As they used to say in the olden days… I might need to actually adjust my voice, which is seriously hoarse.

Susie: A little bit gravelly today.

Peter: Chesty. I do apologise. It’s absolutely fine. I will get there. But anyway, that is the unmistakable, unmistakable lament of the bagpipes. But no, there has been no wine revolution just yet in Scotland or Ireland. I recorded these pipes on the ancient streets of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, while visiting the magical, mysterious, munificent world of Rias Baixas.

Susie: So we’re both very excited because this episode is the first in a cracking two parter on Rías Baixas an intriguing wine region in the northwest of Spain, which isn’t perhaps as well known as it deserves, having been pretty remote and poor and overlooked for much of its recent history. But since the 1980s, it’s undergone a strikingly successful metamorphosis, particularly on the wine front, most notably with the Albariño grape and its signature style of invigorating, refreshing white wine.

Peter: Galicia is a land rich in history and myth. It, used to be perhaps best known for the famous Camino de Santiago pilgrimage, whose ultimate destination is Santiago de compostela, but it was also renowned for its brave seafarers on the costa da morte, or coast of death. It’s quite an evocative name, isn’t it? I’m, not sure I’d fish there. it was also known for its sort of sullen skies, its brooding atmosphere, and even for its terrifying witches. So we’re going to be coming back to that. Nowadays, though, one of its main USP’s, of course, is its wine, having grown its vineyard from a tiny 237 hectares in 1987 to 4480 ha today.

Susie: So we wanted to embark on a proper podcast adventure to find out what’s really going on in Rías Baixas. Here’s a brief taster, of what’s coming up.

Isabel Salgado: Rías Baixas is a magic place. If you compare with other regions in Europe or in other parts of the world, I think it’s a special, special place.

Luisa Freire: All that complexity that we have in the land is in the bottle, too.

Lucia Barbosa: If we can preserve these old vineyards, we have a future

Susie: Winemakers Isabel Salgado of Fillaboa, Luisa Freire of Santiago Ruiz, and Lucia Barbosa of Galegas there. Now we’ll be hearing more from them, as well as many other fascinating people helping tell us the story of Rías Baixas and its wines. Over the course of these two episodes, we’ll also be tasting and recommending some amazing wines as we go.

Peter: Yeah, we should say thank you at this stage to the do Rias Baixas for sponsoring this mini series and enabling us to spend proper time focusing on this fascinating region. as ever, sponsorship ensures airtime, but by no means uncritical appraisal. So we will be speaking our mind as usual. And there’s a lot of stuff to get stuck into, isn’t there?

Susie: There is indeed. So let’s get started. So the plan is to set the scene in this episode, get a feel for the place, meet some of our key personalities, sample the food.

Peter: Yeah, there’s definitely some comedy to come on the food front, I can promise you that.

Susie: And of course, we’re going to get stuck into the wine, something we’ll explore in more depth in part two, where we’re going to focus particularly on the whites and the emblematic local grape, as we’ve said, Albariño.

Peter: Yeah. Now, we should add that we’ve both been lucky enough to get to know this region, haven’t we? beyond tasting a lot over the years, which we’ve done. You, covered Rias Baixas in your book discovering wine country, northern Spain, didn’t you? You had a decent time there. and I visited a couple of times as well, most recently in April to research this podcast mini series.

Susie: Selfless dedication, isn’t it? Has ever. and you came back with lots of little sound effects, didn’t you?

Peter: Little sound effects. Hang on. Me playing around with my little toys, with my little friends. Is that. Is that where we’re going with this?

Susie: I think you did.

Peter: Absolutely. I come bearing sounds. I’d be disappointed if I didn’t. Anyway, how about. I’ve got a few to test out on you. How about a bit of rain or a bit of wild coastal wind? A bit woolly, that one. or finally this one, recorded at the water feature at Pazo de Señorans.

Susie: I think I prefer the last one a bit more gentle and relaxing. I think wind and rain just makes me feel a bit stressed.

Peter: They really do. I think they bring you in a rash, don’t you?

Susie: They do.

Peter: You’re allergic. I know it does, it does. It makes you feel cold. Anyway, thank, you for indulging my little sound effects. They make me happy. So, thank you.

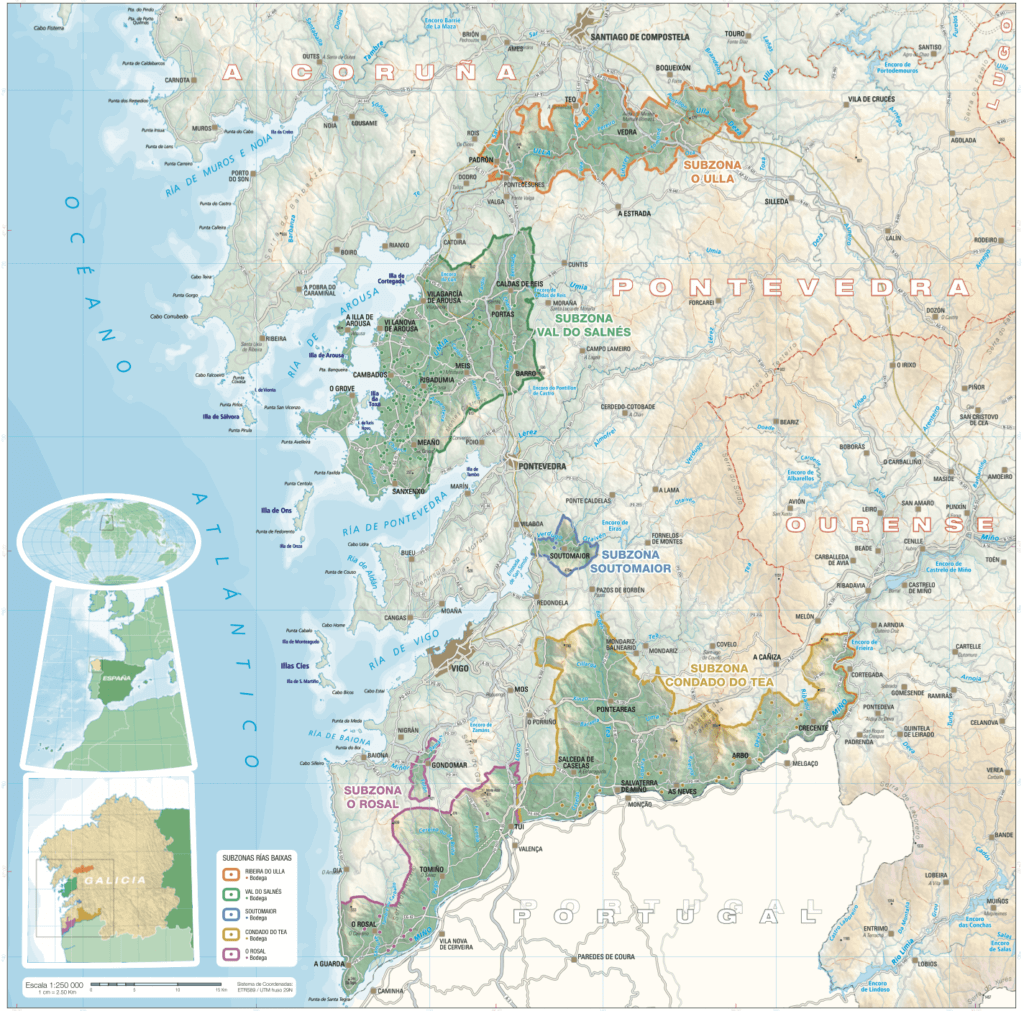

Rias Baixas is dotted around various parts of coastal galician territory

I think the point I’m trying to make in an effort to sort of set the scene is that Rías Baixas is, in one respect, a land of water. the appellation of Rías Baixas is dotted around various parts of coastal galician territory in northwest Spain. So it’s not one contiguous whole, if you see what I mean. It’s not all stuck together, but, arguably, what unites it is water. principally in the form of the Atlantic Ocean, which has a significant influence on the climate, often bringing wind and rain and fog and cloud. Just as importantly, though, it moderates the climate, so it’s not nearly as harsh or as hot as inland or southern Spain.

Susie: You’re right. I mean, it does seem to rain quite a lot in Rías Baixas, doesn’t it? I mean, m even the name Rías Baixas it sort of almost sounds like running water, doesn’t it? and following the same theme, you know, you’ve got the many rivers in the region, including the major Minho river, which forms the border with Portugal in the south of the region. And of course, the rías themselves, you know, which are like a series of narrow inlets that run up the atlantic coast, giving the coast a sort of kind of serrated appearance on the map. and in the Rías you get these big tides mixing fresh river water with salty seawater, creating this amazing environment, which is very rich in nutrients for shellfish and other marine life.

Peter: Which is why fishing and seafood has historically been such a big industry in the area. Yeah. so say the water helps provide food and work and also wine, of course, because one of the main things you notice when you travel around Rías Baixas and Galicia, isn’t it? Is this absolute profusion of green growth.

Susie: Everywhere you look very verdant.

Peter: It’s like the day of the Triffids, isn’t it? The plants are taking over. it’s a landscape overflowing with small holdings that just teem with life. You know, mainly vines running riot over pergolas. It’s sort of Albariño anarchy, if you know what I mean. but also you get things like goats and chickens and vegetables, corn, cabbages, olive trees, lemon trees, palm trees.

Susie: And that actually tells you something else about Rías Baixas, I mean, yes, it can be rainy and cloudy and well watered, but it can also get pretty warm and sunny. I think it has an annual average of over 2000 hours of sunshine. Which, you know, certainly isn’t to be sniffed at. Sniffed over or making you sniff. and I think climate change is actually making things ever warmer, too. So it’s a mistake to think this is cold climate viticulture. You can ripen lemons and oranges and olives here. You know, one winemaker described the local conditions as, and I quote, a mediterranean climate with high pluviometry, which is my new favourite word, pluviometry. I have to confess, I had to go and look it up, but it.

Peter: Almost makes rain sound, sound nice, doesn’t it? Sound proper? Anyway, that is quite funny, but, you know, actually, when I was there, people were talking about irrigation, which gives you an idea of, you know, coming around. But actually, at certain times when it’s hot, they need water. and some vines had even died from water stress, particularly those on the sort of very sandy, granitic soils, very poor soils. That’s interesting to bear in mind, isn’t it? So, kind of puts things into perspective. Equally, while we’re not talking cold climate viticulture, we are talking relatively cool climate viticulture, particularly compared to other wine regions in Spain, I suppose. and that’s reflected in the fresh styles of the wines.

Susie: Absolutely. You know, this is a land of fundamentally refreshing wines. You know, the kind of thing that’s increasingly popular these days, which is music to our ears.

Peter: Hallelujah. Totally. We are all about drinkability and refreshment value. And you can almost see that in the landscape there, you know, everything seems vivid. It’s, a really atmospheric place with its brooding, damp sort of fertile feel, sort of dramatic hillsides and rugged coastline. You feel very sort of close to nature there. You know, it’s a proper land of mists and mellow fruitfulness, as the poet might have said.

Susie: Get you. Clearly, it inspires poetry as well. mind you, given one of the region’s biggest producers, funnily enough, is Martin Codax, and is named after a mediaeval poet and composer. Maybe you are indeed on the money and talking of the people and history, though, that’s also a subject we should touch on as well.

Peter: Absolutely. Absolutely. So I asked a lot about this when I was out there, you know, how people would define or describe the galician character. And, generally the consensus was that the Galicians are, by nature, somewhat reserved. Maybe it’s that cool, rainy climate, bit like, you know, us in us in England, especially initially. But once you get to know them, once they open up, they’re friends for life. So it’s a sort of picture of people who are generally very loyal, very resilient. Very determined, extremely diligent. here’s what stephanie Schilling of Santiago Ruiz had to say. she’s got a valuable perspective as an outsider, originally from Chile, but having lived in Spain for some time, the people.

Stephanie Schilling: The people are really, really, really hard working. Nice. When you get to know them, they’re like super friendly and all that. It’s complicated to get to know them. But then when you are their friends, they invite you always to their homes and are really friendly and very, very honest and transparent. And then they’re very generous and they’re very rewarding and then they’re very straightforward. Sometimes they don’t want to say all what they want to say, but then if they trust you, they do look at where they live. I mean, with, although the kind of weather and, I mean, if you go out there to the sea and have to cut the fish and all that, of course you’re going to be proud that you got the superfish out of the tort. I don’t know, nasty weather. And then you go grape. You grow really good wine.

Susie: Intriguing. You know, complex people do tend to be the most interesting, don’t you think?

Peter: And probably make the best wines. Discuss. What do you think?

Susie: There’s a hypothesis to test out.

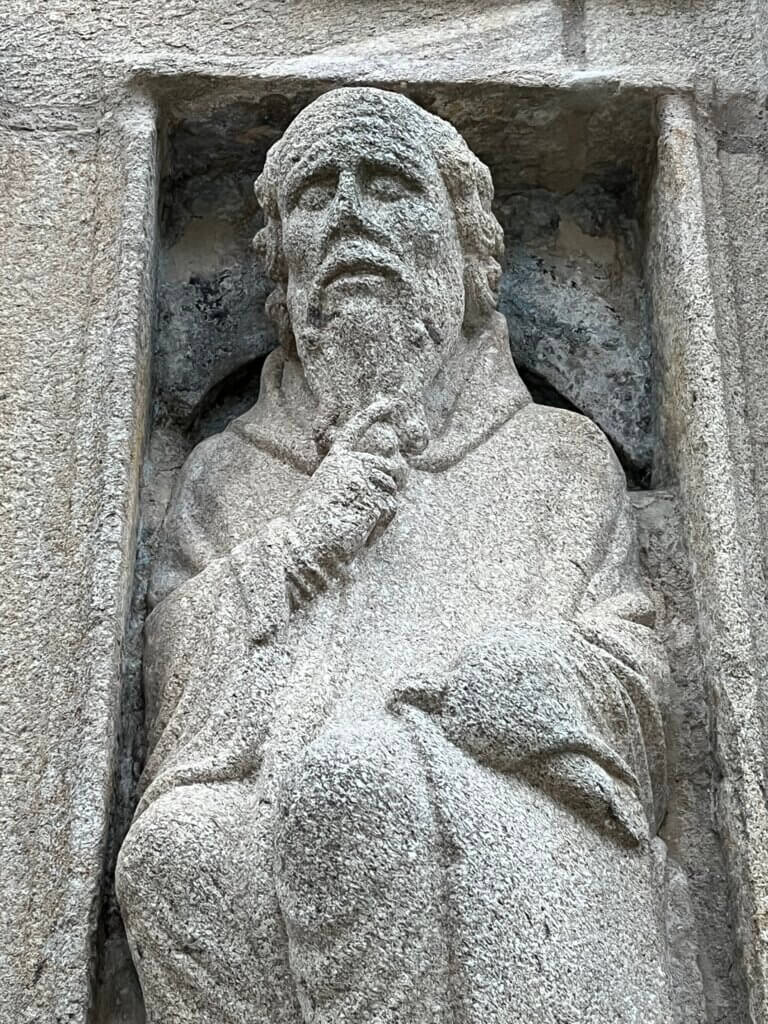

Peter: Yeah. I also touched on this issue with Romina Lopez, a cultural guide with whom I visited the famous Santiago de Compostela cathedral. And for those who haven’t been, this is architectural shock and awe. the facade of this cathedral is just epic. There is no other word for it. It’s massive and so ornate and imposing.

Susie: And, I mean, I guess that part of the point is that this is the culmination, the ultimate destination of the famous Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route, where the shrine of the apostle Saint James is housed. And since mediaeval times, people have made this pilgrimage over huge distances. So when they reach the end, they do expect a pretty big payoff. And it doesn’t disappoint.

Peter: It certainly doesn’t. at least on the outside. Inside, I found it intriguing because, yes, you do get this remarkably ornate and baroque centrepiece where the holy relics are enshrined, as you said. But then the rest of the interior is actually quite pared back and restrained and sort of romanesque in style. It’s certainly not as lavish or opulent as I was expecting.

Susie: Maybe you were focusing too much on the money or investment brought in by all the pilgrims over the years, so expected a bit more blame.

Peter: I was expecting more bling for the buck.

Susie: but this was big business, particularly in the day, wasn’t it?

Peter: Yeah, it’s a good point, and it still is. You know, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims come every year. I mean, not all religious, but that they come. and just as importantly for Galicia in the past, it didn’t just bring in foreign investment in the local economy. It also brought knowledge, and it’s assumed, you know, religious people tending to be partial to wine, of course. Fantastic. A fair bit of wine knowledge came with that, with that pilgrimage, too. So, you know, you could see it, as the religion, religious pilgrimages helping pave the way for our wine pilgrimages to the region today. Does that work?

Susie: I think it does.

Peter: It’s an interesting notion.

Susie: Why not? Why not? But what did Romina have to say?

Peter: Yeah, sorry. We sat down in the cathedral for a very brief chat, and I asked her to describe galician people.

Romina Lopez: We are people very proud of, our history, very proud of our, region, of our landscape, of our lifestyle.

Peter: Now we’re sitting in the magnificent Santiago de compostela cathedral, and so many people throughout history came on a very long, very famous pilgrimage to this place. How important is the pilgrimage to this part of the world?

Romina Lopez: it has been incredibly important because, pilgrims made us, the people we are. So our identity is totally linked to, this pilgrimage. M religion, being christian, m all the cultural aspects related to the way brought by pilgrims over centuries.

Peter: And Galicia for a long time was quite a remote part of Europe. It was hard to get to. It was cut off by mountains. How important was the pilgrimage in terms of bringing people here, bringing their knowledge here and their money as well, I suppose.

Romina Lopez: I think that thanks to pilgrims, the north of Spain, not only Galicia is, as it is, so otherwise, this region that was very autonomous, independent, but also not well communicated with, the rest of Spain and Europe, would be very different. So in, our, current character and personality versus pilgrims, what pilgrims brought is incredibly important.

Peter: And we’re looking at this cathedral. It’s funny because you look one way and it’s very pared back and actually quite elegant and simple, and then you look the other way and there’s this amazing, ornate, baroque sort of element to the cathedral. And you said this sort of sums up the galician character. Can you just tell me about that?

Romina Lopez: Well, that’s very personal. It’s my opinion. So I think we can be both. We can be very simple, but in a positive way. we can be austere, we can be elegant, like romanesque, but sometimes we can be very overwhelming, in many senses, like the baroque.

Galicia has a reputation for magic, for witchcraft

Peter: Now, it seems almost sacrilege to bring this up sitting in a cathedral, but Galicia has, a reputation for magic, for witchcraft, and this sort of wonderful, sort of alternative reality. Can you just explain a little bit about why that is?

Romina Lopez: Well, in my opinion, there were many, mysteries about Galicia because due to the lack of connection, probably this area became a little unknown, for the rest of Spain and Europe, and that caused sometimes, confusions. And this happened with the witches. so they were actually healers. healers were not only in Galicia, but, in or Europe.

Peter: So it was sort of a case of mistaken identity or maybe just people filling in the gaps with their imagination about a region that wasn’t very well known and misunderstanding things.

Romina Lopez: It is nice to think, that the Galicia is a land full of witches, because it’s, foggy, hilly, the atlantic ocean. And, well, probably all this helps to create the myth of the galician witches.

Susie: You can see that happening, can’t you? You know, you get this remote region that’s misty and mysterious and people start making up myths.

Peter: Yeah. And the other element that’s key here, which is really intriguing about this part of the world, I’m sure you agree, is the importance and prominence of women in society. And this is particularly noticeable in winemaking circles. You know, on my trip, for example, I didn’t meet one male winemaker.

Susie: Really?

Peter: Yeah.

Susie: That is quite unusual.

Peter: It’s a small sample, but still, you know, it is also something that’s generally remarked upon.

Susie: Yeah. I mean, it’s always hard to generalise about these things, isn’t it? But what I understood was that historically, the men in coastal Galicia would be out on the boats for long periods, so the women simply had to take care of everything, including the winemaking. And this then perhaps extended to when Galicia was in a really bad way in the 20th century and many men emigrated to find better opportunities, often to the Americas.

Peter: Yeah, yeah. So I actually asked, winemaker Susana Perez of Pazo San Mauro about this, and she had Maria translating for her. And this is what they said when I asked about the prominence of female winemakers in rias baixas escurioso esta pregunta la.

Susana Perez: La escucado masve sine embargo que nosotros no lo percevi moscomo algorado.

Maria: In Galicia. It’s very, very traditional. It’s a normal, thing. Women, are always being responsible for the hard works in this area. Normally, the husband men of the family went out to work, but, the woman is, responsible for the children, for the vineyard, for everything. So it’s a traditional way lifestyle here. It’s not, something strange for them.

Peter: It’s a matriarchy here.

Maria: Yes.

Susana Perez: Matriarchy, exactly.

Susie: So I’m liking the Rías Baixas wine scene more and more.

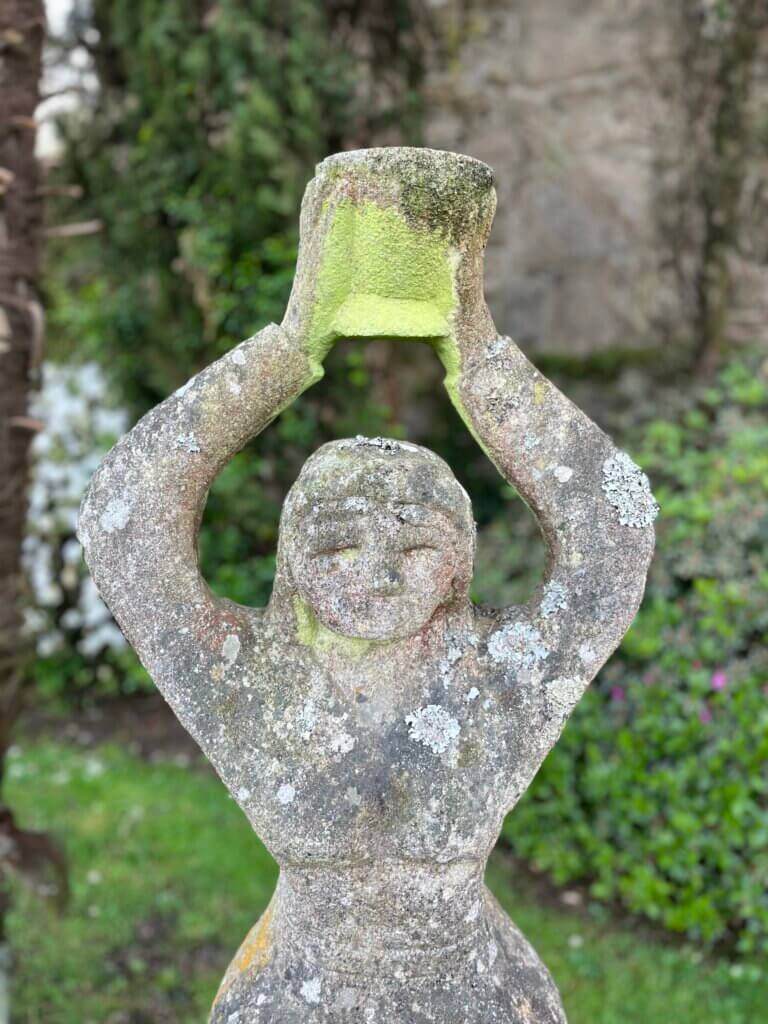

Peter: Yeah, I’m sure you are. I have to say, though, it did make me smile, thinking about this witchcraft mythology. But, then being taken around all these funky wineries with their delicious potions being brewed in all kinds of pots and cauldrons and amphora and concrete eggs and granite tanks,

Susie: All the tools of the modern magician wine maker. so I think we should take a quick break there before we come back to talk about the food and wine. To recap, so far, Rías Baixas is a unique wine region on Spain’s northwest atlantic coast, where vines run riot and the people are fiercely proud of their heritage and produce wine included. So much so that these days, pilgrims aren’t just coming for religious or spiritual purposes. They also come for the wine.

Peter: I guess you could class me as a wine pilgrim.

Susie: I think we can definitely do that.

Peter: I’m noble and spiritual. I think. I think I fit into that category. I’m definitely more of a wine pilgrim. Tell you what, I am definitely more of a wine pilgrim than a bagpipe pilgrim.

Susie: Yeah.

Peter: I have to say, on which note, though, we probably should have added, in our cultural context, that this region has a strong, celtic heritage, like parts of the UK. which is why the bagpipes are part of local culture and history, just to clear that one up.

Susie: I’m glad we have cleared that up, because now we’re going to move on to the food and wine. And didn’t I read something recently about the benefits of the atlantic diet?

Peter: Exactly. Exactly. Yes. So this is really interesting. We’ll post a, link to this piece on our show notes. But basically, a clinical trial was conducted into the traditional diet in this part of Spain. So, you know, rich in seafood, fruit, vegetables, but also with meat and dairy, potatoes, and, of course, a nice bit of wine we have to add, you know, and this was dubbed the atlantic diet. and recent analysis of this study found this diet could make it just as healthy as the more famous mediterranean diet. you know, reducing the risk of type two diabetes and heart related conditions, that kind of thing.

Susie: I guess it’s not a big surprise, given we’re essentially talking about really fresh produce often locally sourced and seasonal, prepared and served very simply. You know, you’ve got lots of variety, lots of seafood, and also a society that’s quite convivial, you know, with lots of family meals and sharing of food.

Peter: And all that is so important, isn’t it? I totally agree. Fair enough. But the food there, just, just to stop. The food is so good, isn’t it?

Susie: It really, really is so good.

Peter: I mean, what would be our favourite dishes?

Susie: well, I mean, the seafood generally is just sensational. and like we’ve said, done so simply. Octopus, is the classic. Just this big chunk of meaty, succulent octopus with olive oil and paprika. Yeah. Which often they sort of serve on potatoes, don’t they?

Peter: Yeah. But then you’ve got lovely mussels and clams and oysters and sea urchins. I mean, not to mention all the gorgeous fish like the monkfish I had.

Susie: Didn’t you have a run in with a sea urchin? just talking of sea urchins, while you were in Rias Baixas why do.

Peter: You have to bring up all the traumatic events? What is it with this line of questioning? It’s not very common kind. No, you’re quite right. I was coming up to that. Essentially, I really wanted to experience the seafood sector while I was out there in the region. And instead of sort of kitting me out in a deep sea diver’s seat and chucking me off a boat, which you probably would have done. I don’t know that I would they. Well, I shudder to think what you would. Anyway, they took me to one of the region’s top shellfish producers and wholesalers, Mariscos Laureano

Susie: And what did you find?

Peter: loads and loads of sea creatures, really. oysters, clams, mussels, barnacles, sea urchins, as you said, scallops, crabs, you know, razor clams, cockles. I kind of ran out of english names after a while.

Susie: Wow.

Peter: But can I. Can I just by way of brief interlude for local colour, can I play you a recording of what these things are? But in Galego, the local language, more little sounds.

Susie: Bring it on.

Fernando Oubina: Ostras amicias, birbericos, navallias, amaichons. Michelon. Ostraplana ostrarizada cornichas, amasia fina. Amicia japonica. Amesia. Vagosa. Camarong. Bogavante. Necora centolo.

Peter: Fernando Oubiña there, who. Well, come back to in a second. but it gives you an idea of the bounties of the sea. Here doesnt it? Its also lovely. Just, can I say, to hear Galego, you know, testament to the fierce spirit of independence and local identity here. so these shellfish have been collected from the Rias. many are farmed off floating platforms called bateas. and these shellfish were all in a series of tanks in this massive sort of warehouse being purified before being shipped off to top restaurants all around Europe.

Susie: Please, please tell me that you tucked in. Please.

Peter: I did, I did slightly. I am glad I’m glaring against my better judgement. it was pretty early in the morning and I just brushed my teeth. so there I was, this sort of slightly green around the guilds Brit, you know, at the crack of dawn, a bit woolly, surrounded by there may have been things the night before, but I was surrounded by these sort of grizzled sea dogs and armies of crustaceans. Before I knew it I was manhandling sea urchins, then tasting their innards and eggs after they’ve been split open with a strong knife.

Susie: I’d have loved to see your face when that happened.

Peter: You can actually, because I did record it for Instagram so we’re going to put that on Instagram for anyone’s interested. We might try and find some photos for the show notes as well. But anyway, the lengths I go to for this podcast now that particular experience did test my metal a bit, I’ll be honest. but I was brave. You’d be very proud of me. And actually the flavour was very subtle and delicate and actually quite beautiful. But then I was taste testing the difference between Pacific and flat oysters. And m the Pacific ones are more intense and sweeter and finer. For what it’s worth. I was inspecting how they used concrete to glue baby oysters to wooden planks to then grow on when they put them out. I was slobbering up razor clams squeezed fresh out of their tubes. it was all, I mean just the most feat, a feast for the senses. But it did make my head spin a bit.

Susie: I can’t, I just, I can just picture you. I can’t help but laugh at the thought of you, Peter Richards, having to do all that with a very polite smile, which I’m sure you did, as ever I did. But also I think for me as a massive, massive shellfish lover, it is making me quite jealous. I mean I think all that was missing quite clearly was a nice glass of Alberini to wash it down, wasn’t it?

Peter: Well, it’s funny you say that actually, because as it happens, Laureano and his wife Guadalupe and son Fernando, who we just heard from, have been so successful with the shellfish business that they launched their own wine brand.

Susie: Oh yeah.

Peter: So it makes sense, doesn’t it?

Susie: Made for shellfish.

Peter: Indeed. So I took the chance while I was there to ask Fernando for some specialist advice, and you’d have liked this, I think I could hear you in my ear just saying, ask these questions. So they make three styles of Albariño in Val do Salness under the Laureatus label. One is a fresh young style, another is a bit more complex, having been aged on the lees, or it’s called the Lias. And the final one, called Dollium, is matured in oak. So the richest and creamier style. I asked Fernando what shellfish he would choose to match each of these wines. He started with his choice for the fresh young style of wine.

Fernando Oubina: Clams and oysters.

Peter: Clams and oysters, okay, then we come onto the lees aged Albariño What would you put with that?

Fernando Oubina: With, for example, a good plate is clams or crabs that boiled and in green sauce. And for lauda terzoleum for example, is barnacles.

Peter: barnacles, is that right?

Fernando Oubina: Yes, yes, yes.

Peter: So for the ok’s wine you’re going barnacles?

Fernando Oubina: Yes, yes. The barnacles have a very intense, is more that meat. No, that beef, that shellfish and half as strong, or ah, for example, other thing is for, the grill, lobsters, no, the dollum is perfect for.

Peter: How are you serving that lobster with a sauce?

Fernando Oubina: No, for me the lobster is very easy, it’s a good grill. No, a good olive oil only. And don’t need more no sound, have a lot of sows, of course. But if the good quality, the galician blue, is different than my respect with canadian American, that is orange, but the blue here on galician, the blue lobster is on grill. It’s fantastic, it’s amazing.

Peter: I just want to go and eat that now.

Susie: I think we should stop this podcast right now. Go and find some lobster, cook it up and serve it with olive oil and an elegantly oak Rias Baixas Albariño And could life seriously get any better?

Peter: I’m with you, I am with you on that one, but I think it might be polite just to finish up first. Ah, maybe we should, but we can delay our gratitude. My word, I mean, just to add the Lauriatus Lias alberini was a lovely mix of freshness and bready richness and it worked really well as a palate cleanser after a truckload of oysters that I, that I’d necked.

Susie: so it is true, though, that a lot of Rias Baixas whites, particularly the Albariños from Valdesalnes, do have a lovely salty, saline, almost briny hint on the finish, don’t they? Which not only makes a nice counterpoint to the other flavours in the wine and whether that’s fresh fruit or bready richness from lees or more toasty creaminess from oak, but it also means they work beautifully with fish and shellfish.

Peter: Spot on. You know, it’s a marriage made in heaven. One of the all time classics in the wine and food matching pantheon, isn’t it? Rias Baixas Albariño with fresh shellfish. mind you, before we move on from the topic of food, there is one, cautionary tale I did just want to drop in.

Susie: Go on, go on.

Peter: Lampreys, beware lampreys, sometimes called lamprey eels. more especially, beware lampreys stew, when served by a proud home chef, touting it as a special local recipe. When it’s dark as the night in the pot and with strange things bobbing around in it. Just don’t go there.

Susie: Ah, you didn’t.

Peter: I did, I did. I thought I still had my polite smile on and I thought, no, I’m gonna be a gracious guest. And boy, did I regret it. Oh, my. I mean, it tasted like if you boiled leather and decades old biltong with a kind of whale carcass and strained it through coal and eaten it off warm asphalt with added mange too. I mean, I struggled my way through it, but I was still tasting it on the plane home. No, amount of mouthwash or Albariño could shift it. It really was quite something.

Susie: So we don’t just focus on the finer things in life, elegant fine dining in this pod, do we? It’s warts and all. yeah. But to move on, what did you make of the wines? Generally speaking?

Peter: Yeah. well, I’m not sure any quite stood up to lamprey stew you, that’s why.

Susie: No, I can imagine not.

Peter: That is a big question, and one I think it will probably take the full two episodes to answer, in a good way. There’s so much to say. generally the quality is impressive, as is, and this is important, the diversity. there’s so much more to Rias, Baixas than just fresh quaffing Albariño

Susie: I know we’re going to get into that, aren’t we? A bit, in the next episode, looking at the diversity of Albariño and the whites, both in terms of winemaking, but also terroir, looking at the different subzones like Salnes, condado do tea and O Rosal But it goes beyond that as well, doesn’t it?

Peter: Absolutely, absolutely. There’s so many things going on. People ageing, wines in the ocean, people making orange wine, natural wine, no sulphite wine, all kinds of stuff. there’s so much potential. But there were two styles I particularly wanted to flag up in this alternative context, as it were. And they are sparkling and red, both.

Susie: Of which are pretty tiny categories in the region as things stand on.

Peter: Yes, it’s true, but that may change over time and I think, I don’t know, they showcase the potential of the region looking to the future. take red wine, for example. Historically, red was actually a big part of the region’s production, but that was when it was pretty basic plonk And there were often sort of totally unsuitable grape varieties, like alicante, boucher hybrids in there. Then everyone replanted with things like Albariño which was good, but it meant some of the old local red varieties sort of faded into obscurity.

Susie: And some were on the brink of oblivion really, weren’t they?

Peter: Absolutely. And given the warming climate and general global trends towards juicy, fresh, lighter styles of red, some Riaspaixas producers are reviving varieties like espadeiro, Suzon, caino, tinto, Brancilao, Mencia, Castanial and Pedral There were only 16 producers making red wine in 2010, but there are 45 now. so it’s growing. one producer in particular doing this is Senorio de rubios in Condado dotea, which works with lots of smaller growers. So I asked Natalia Rodriguez to tell me more.

Natalia Rodriguez: We are the winery in Rias Baixas that elaborate most quantity of, ah, red varieties and work with all varieties that Rias baisas allow. Ah, the castanal. But we work with the Sozon, Espadeiro, cahino, Mencia, pedral, brancellao, Laura, Iratinta. And in the case, for example, of the pedral, is a validity that we recuperate in 2011 that, is possible, disappear. But, nowadays we are increasing the quantity that the laborator of pedral.

Peter: So I’m not sure, lots of people wouldn’t be familiar with riospices red. So can you just give us an introduction. What’s the typical flavour profile? What can we expect from a Rías

Natalia Rodriguez: Baixas red, rias, baixas red are wines very fruity. Red fruit, blueberry, raspberry with, a touch of acidity, and tannins. But are wines with very expressive is the influence of the Atlantic Ocean, without oak, for example, in our cayennes, we don’t use the oak because we prefer when people taste the wine, taste the particularity of the wine. And our wines easy to drink, but with this touch of acidity that sometimes very surprise for the people. There are people that accept well and others need more time for adapt, to this kind of wines.

Peter: So we’re talking about fresh, bright, juicy, crunchy reds. You said sometimes they can surprise people. So do you think we’re going to see more and more Ria Baixas red? Do you think, it’s a category that’s going to grow?

Natalia Rodriguez: Yes, I think it grows. The way is, step by step. And it’s slow if you compare with the whites. But for example, the winery what found it. And the first vintage is 2005. And, in 2005, the quantity of red in rias baixas is minimum. Nowadays it’s perhaps four or 5% in rias baizas. But there are a lot of wineries that decide to work with this kind of, ah, grapes, indigenous grape and native grapes. Because it’s the grapes that better express the particularity of rias baizas. The atlantic ocean, this climate, and this terroir. And for us it’s very important. And it’s true. There are people in the international market that look, for and search this kind of, wines without oak. More fruity, more fresh, more crispy. And I think, it’s a good idea.

Peter: Do you think climate change is having an impact as well?

Natalia Rodriguez: I think climate change is a problem. For example, in the white varieties, it’s a big problem because, increase the alcohol, the acidity. And, is not good for the white varieties. It’s good for the red varieties because the normal alcohol is, eleven and in the last years increased to twelve. But it’s good for the white, the red. But the climate change is not good for the vineyards and for the production. And we need to, to doing different kind of things and actions for avoiding the climate change.

Peter: You talk about the importance of recuperating, reviving history. Do you think that the traditions have got a bit lost in this area nowadays?

Natalia Rodriguez: No, but, I think when we founded the winery, it’s possible some kind of paradise, lost. For example, the pedral. Pedral is a grape that we recuperate in 2011 and the first time we only elaborate. A hundred kilos. Nowadays we are in 12,000 kilos, more or less is a small quantity, but the process is, a process of recuperation. But, I think if the winery don’t exist, it’s possible some kind of barrities disappear.

Susie: So we’ll be coming back to the issue of climate change in part two. But in the meantime, that’s intriguing, you know, rescuing pedral from the verge of extinction. I mean, I must admit I haven’t tried many Rías Baixius reds.

Peter: Well, neither had I before I went. And I’m not sure if any people get the chance to, And it’s true to say, you know, there are some, you know, reas baitous reds that are pretty mean and green and murky, old school in all the wrong sense of the word, but there are some really good ones now too, you know, I like the senorillo de Rías espadeiro, which was sort of full of graphite and meaty and grippy, maybe a bit rustic, but those sort of flavours. I also liked their menthia, which was really juicy and fresh and upbeat, really lovely. I also was really impressed with the red ze attis, which is a really funky producer in salerness making all kinds of wine.

Susie: We’re going to be looking at them, aren’t we, in a bit more detail in the next episode?

Peter: Exactly. But, you know, for example, they had a pedral, that was superb. You know, it was all sort of dried flowers and bitter berries, herbal tones, you know, kind of like if you crossed burgundy with beaujolais and Loire, Cabernet franc in that mix. Sort of a bit like good manthea, really, I suppose. And it was only 12% alcohol, you know, again, lighter, gastronomic, so a really good one to rescue. but also then Attis Caillo tinto was superb, and their espadeiro was just heavenly, you know, really juicy, bittersweet food friendly, amazing. So these reds really do have potential.

Susie: Rias Baixas reds. Coming to a table near you soon. Now, you mentioned sparkling too.

Peter: Yeah. So, if you think about Albariño you know, it’s high acid and responds brilliantly to Lees ageing and bottle ageing. Both things we’re going to come on to in the next episode. Both of those things are, ah, what happened with traditional methods. Champagne style, sparkling wine. Right. So you can charge good money for fizz. This is a style that Albariño can do. We join the dots.

Susie: Real Baixas, Producers are starting to move into fizz.

Peter: Yeah, exactly. So a few are, For example, Isabel Salgado at Fillaboa had just been on a research trip to champagne. When I spoke to her. She’d been touring the growers and she said she’d be looking to make some traditional methods. Sparkling wine, maybe with a base wine fermented in oak and long lees age sort of along the grower starter that’s had a really interesting.

Susie: And did you try some that you liked when you were out there?

Peter: Absolutely, too. So, yeah. At, Pazo de Almuíña with, winemaker Lucia Barbosa from Galegas who we heard from at the beginning, this was Albariño aged for 40 months on the lees, and it was lovely. So sort of apple y and bready and savoury and fine. Really good potential there. Apparently, they’ve done experiments starting with twelve months on the lees. Nine months is the minimum for the appellation. But then they worked up and they may end up now trying 60 months next, which I’d really encourage, you know. Anyway, I asked Lucia, why she’s keen to make sparkling with Albariño in.

Lucia Barbosa: Rias Baixas in the world, which is the best, wine product that most, people want to pay and think, wow, when we make a party, which is the one that we pick to celebrate, is champagne. No. So we have here a spectacular grape, that is Alvarino. So everybody recognises that is a grape that have a lot of potential to age for many years. So why we don’t try to do this kind of product, with this amazing grape that is from here and.

Peter: You’Re doing this long lees ageing. So the sort of traditional method, the champagne method, as it were. But you’re sort of, as far as I understand, you’re giving it more and more age on the lees. Why are you doing that?

Lucia Barbosa: So it’s like a challenge? No, we can do this in a good way. We are now able to do this because we are doing for several years and now it’s like a challenge, how we can put Alvarino in the world class, fine wines in the world, showing, like the good wines. White wines have the world, I suppose.

Peter: Chardonnay makes great still wines, great oaked wines, great unoque wines and great sparkling wines as well.

Lucia Barbosa: Exactly. Is that the idea, ah, is like a challenge. Chardonnay. Do that. Now, what is the next big white, grape? I don’t know. Maybe we can have, something to say about it with Albariño, maybe.

Peter: So if chardonnay can do it, anything Chardonnay can do, Alvarino can do, too.

Lucia Barbosa: It’s not like that. But we need to. To try.

Susie: If you don’t try, you don’t know. M and I agree, you know, it could work really well.

Peter: Do you think so? I mean, I think it could be something that’s pretty good.

Susie: Yeah. Yeah. Who knows? Let’s see. Anyway, we need to wrap up, but just before we do, you’ve managed to recommend some wines, and so now I wanted to recommend a couple we tried at home.

Peter: Fair enough. Go. Go for it.

Susie: Okay, so, first up is actually a wine made by Lucia at Gallegas, and it’s the Veigadares Branco de Brancos 2021. It’s, new to the market, and it’s a blend mainly Albariño but with bits of treasure. Dura, lourero, caino blanco. The albarino was fermented in large wooden foudra. And it’s pitch perfect. Real Baixas, White, isn’t it? You smell that?

Peter: It’s gorgeous.

Susie: You’ve got lovely, fresh, peachy, lemony fruit, and then that yeasty, honeyed complexity. And in your mouth, really layered, a lovely kind of chalky texture. Seriously stylish stuff. And age worthy, too. You know, this is actually. It’s a bit younger. 20.

Peter: Yeah, I agree. I mean, I tried this against the 2020, while I was there with them. Both were excellent. But, you know, these wines, you can just see that they will improve with age in the bottle, and they absolutely do. I love that really discreet touch of oak here. And the Lee’s work as well. It’s just beautiful.

Susie: Very elegant, very balanced, isn’t it? And then one other to recommend, in a slightly, I would say, contrasting style, is the Adegas Valmiñor Davila M 100 2018. Now, this is also a blend Lureira, caillino blanco and Albariño also aged in large wooden fudra. But then part of the blend is aged in smaller hungarian and french oak barrels, too. And then, of course, you’ve got bottle age, and I think this is six years old now. So you get this really complex, evolved character typical of these wines when they age. But here you’ve got notes of clotted cream and freshly baked pastries. However, it is balanced by that lovely red apple freshness and just a hint. A salty hint. Faint salty hint on the finish. It’s just lovely.

Peter: It’s so nice when these wines are given some bottle age.

Susie: Yeah, no, it really is.

Peter: Yeah. They become so much more rounded and complex and intriguing. So, you know, you get the inherent freshness and fruit, but you also get these extra layers of flavour and generous texture. that’s something we’re going to be coming back to you in our next episode. The topic of ageing.

Susie: Yeah. Lots of ground still to cover, lots of debate to be had, lots of wine to be drunk. including an absolute gem from the 2003 vintage. So a venerable Rías Baixas white that is over 20 years old. Do not miss it. In the meantime, we need to do a quick recap on this episode. Over to you.

Peter: Gracias. So, Rias Baixas is a land of mists, myths and mariscos. that’s shellfish, but it didn’t work with my alliteration, so I’ll just get my coat. Yeah. The rolling hills and verdant vineyards of Spain’s northwest atlantic coast make for invigorating, food friendly whites that work beautifully with all kinds of dishes, but particularly the local seafood. The wine scene has been revived to dramatic effect since the 1980s and now the wines are more diverse than ever, including red, sparkling and beyond. The future is looking exciting.

Susie: Cheers to that. Our, thanks to the DO Rías Baixas for sponsoring this episode. Also, to everyone we heard from in this episode, including Stephanie Schilling, Romina Lopez, Susana Perez, Fernando Oubiña, Natalia Rodriguez and Lucia Barbosa don’t miss the next and, concluding part in this miniseries. Thanks also to you for listening. Until next time, cheers.