- Becoming a Master of Wine Part 1

- Becoming a Master of Wine Part 2

- Big English Wine Adventure

- Bordeaux in 2021

- Build a Wine Collection at Home

- Dry Drinking

- Canada and Crisps

- Napa + wine on screen

- Glass Works

- Dreaming of a wine Christmas

- Burgundy in 2021 Part 1

- Burgundy in 2021 Part 2

- New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc

- Our Story, Part 1

- Our Story, Part 2

- Season Two Trailer

- Sommeliers – What Next?!

- Spread the Love – with Majestic Wine

- The Sam Neill EXCLUSIVE

- The Undeserved Hangover

- Wine can be a career?! (Re-run)

Summary

To kick off 2021, we dive right into the fascinating, frustrating, compelling wine world that is Burgundy.

Iconic – certainly. Over-priced? Plausibly. At great risk from climate change? Undoubtedly. We explore these issues and more across two special episodes – and in this first part we quiz our fellow Master of Wine and renowned Burgundy expert, Jasper Morris, as well as buyer Rebecca Palmer from Corney & Barrow, agents for Domaine de la Romanée-Conti (among other things).

We give our summary on the 2019 vintage, which is currently going on sale, explore how to find good value, the new generation, alternatives to Burgundy and biodynamics, all in the time in takes to sink a fine bottle of Passetoutgrains. Or Chambertin.

Running Order

- Introductory quote: 2.18

- Preface of terms: 4.25

- Interview with Jasper Morris MW: 11.01

- Our summary of the 2019 vintage: 34.18

- Interview with Rebecca Palmer: 40.35

Starring

- Jasper Morris MW

- Rebecca Palmer of Corney & Barrow

- Susie & Peter

Notes

- In this episode, we also explain terms like En Primeur, Hospices de Beaune, brett, sulfur, whole bunch, Robert Parker and Passetoutgrains.

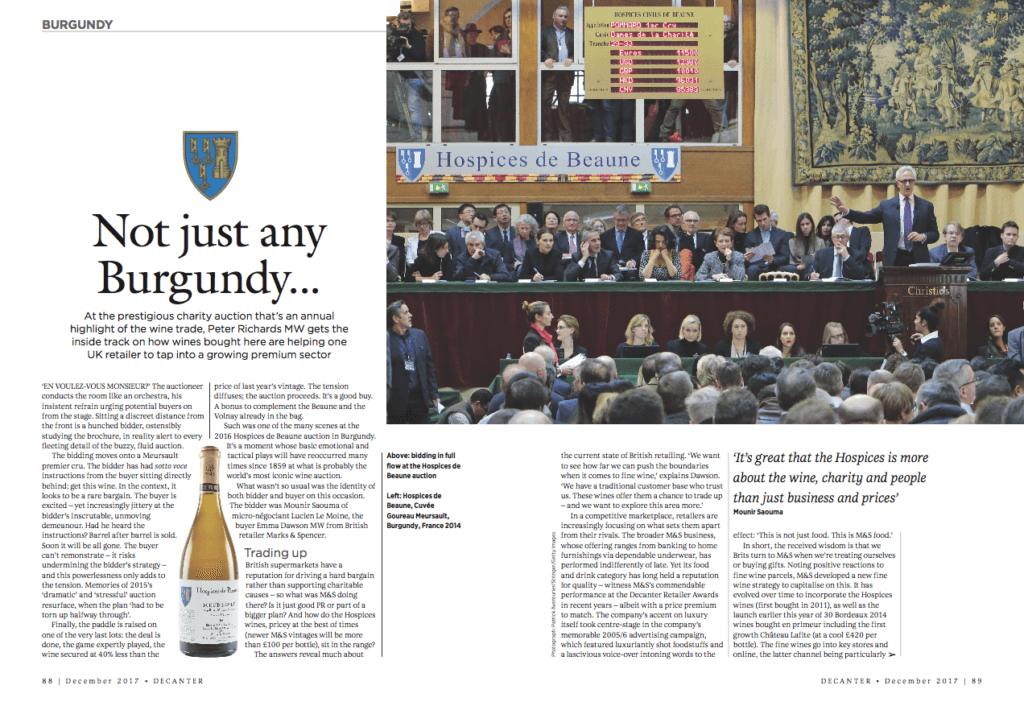

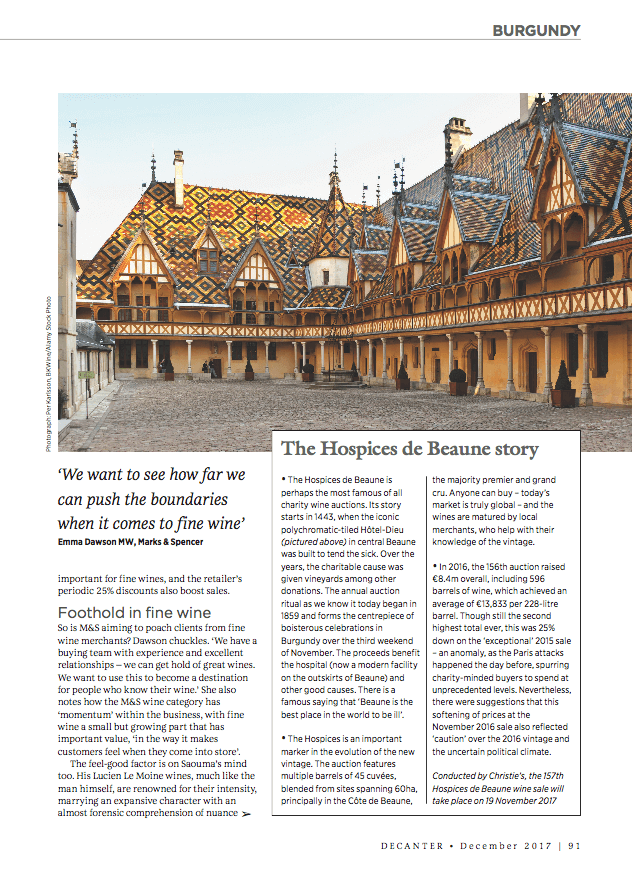

Hospices de Beaune article

Click on this link to download Peter’s Hospices de Beaune article, which was published in Decanter magazine in December 2017. Some images of the piece are also below.

Jasper Morris MW interview transcript

Jasper Morris (JM): Oddly enough, it doesn’t feel much different from usual, insofar as it’s a rural community so everybody can get out and about. Even in the first lockdown people could get out and work in the vineyards. There’ve been a few cases of Covid but actually it’s building now in the Cote d’Or department and we’re probably about to be put on a 6pm curfew from this weekend. But it’s much more in the towns and so the producers themselves are not really feeling it. They’re sorry they can’t come to London but they can do the essential work.

Susie Barrie (SB): Are they worried, if they can’t show their wines, about sales? Or do they feel that’s not gonna be a problem.

JM: Frankly, Brexit is more of a problem in that area I suspect than Covid. But yes sure they’d love to be in London, many have sent samples to leading UK importers. Some don’t want to do that, it’s pretty tricky sending out samples of unbottled wines. If they can travel with them and taste, to verify each bottle, that’s fine. Once they get divided into small smaller samples, that’s a little bit tricky. Some have been happy to do that, importers have clearly worked hard on this, developed their own communications, Zoom shows, and finding a good response from it.

SB: One potential casualty of Covid last year was the famous Hospices de Beaune annual wine auction, which was postponed, but when it happened a few weeks late, it raised over €14m, 2nd highest ever. You’re involved, working with Christies. How important was it that the auction took place in 2020?

JM: I think very important. I’ve put it behind me now but it really was a desperate moment because it was on again off again and it was supposed to take place on Sun 15th November and there had been discussions all the way through, and at 7pm on the Saturday it was postponed. Some people in Beaune wanted it not to happen until they could open their shops and restaurants, to take advantage of the big tourism effect of the auction. But it was clear, as now, that this just wasn’t going to happen. So fortunately another viewpointprevailed, and it was held before Christmas, when we still had the original bids in place, didn’t remove those, gained a few extra ones, out of solidarity for difficult times. As ever we never know until the day which way it’s gonna go, and we were so thrilled the solidarity was there and we got such a good result, admittedly for really good wines in 2020.

SB: Tell us – where the money goes to that’s raised in the auction.

JM: Apart form the single very special barrel, Pièce des Presidents, which goes to single nominated charity 100%. The rest goes to the hospital of Beaune and 3 surrounding towns, their hospitals, it enables them to build new wing, bring in scanning equipment, or whatever. It’s a municipal project, but incredible the support we get for it.

SB: Moving onto the 2019 vintage – it’s considered very good but also quite surprising… The words ‘baffling, bemusing’ has been used as it was very dry and hot and yet the wines are showing freshness and purity along with concentration and richness. What’s your take on why this might be?

JM: I liked your ‘bewitched, bothered and bewildered’! 2018 is the turning point. Before that we had a number of very warm vintages, which were well received, maybe not 2003 but 2005, 2009, 2015. And then 2018 just felt different. Because for the first time, things could go clearly too far. But if you were able to pick at the right moment – and that remains key – then you could make some spectacular wines. So 2018 caught people by surprise, 2019…

SB: To do with climate change?

JM: Yes, entirely. 2019 on the whole worked better than 2018. Not quite unfirom for everybody. Pretty good white wine vintage – and we know Chardonnay works pretty well around the world at a range of temperatures and alcohol and ripeness levels, eg some great California or Australian Chardonnay that can push up towards 15%. So not so much of a worry if you’re getting up to 14-14.5%.

Pinot Noir typically has not liked this. So people have been frightened. But actually 2019 has proved more of a red vintage than a white. There are some failures but also some utterly gorgeous wines. Admittedly in a rich and succulent but still very pure style. Some people will prefer things that are more angular, restrained. So maybe that’s not their vintage. But nonetheless, super sumptuous, really good.

SB: However good, we all know how eye-wateringly expensive the wines can be in Burgundy now, beyond the budget of most of us. Any particular commune you’d single out as offering particularly good value in this vintage?

JM: Yes. Personally, I can’t afford where the 1ers Crus and Grands Crus have got to. But there’s so much good stuff to had in Burgundy, more than ever before, in the less well known villages, more so than ever before, partly because knowledge spreading, more people switched on, also perhaps because global warming helps some of these sites that were perhaps a little bit too cool before. So I’ve been doing a lot of walking round the vineyards, calling on vignerons in vineyards like St Romain, Auxey Duresses, Monthelie, Marsannay, and finding things that I’m really happy to drink. And I’m not resenting at all not being on grand allocation lists.

SB: So for drinkers, it’s better that these areas are now a bit warmer, making better wines but still selling at the price they’ve always sold at traditionally?

JM: Broadly speaking, yes. That’s accurate. We’ve seen with the start of global warming the quality going up the vineyards. However, they’re also drier as a whole as got a lot less topsoil at the top of slopes. But now with 2018, 2019, 2020, we’re seeing interest more towards the bottom of the slopes, where the soils tended to be too humid and tannins rustic, wines not that exciting, but the basic Bourgognes, red or white, from bottom of slopes, are looking really interesting now.

SB: So that’s one option in the face of global warming. Will it ever go so far when people have reconsider Chardonnay and in particular Pinot Noir?

JM: I don’t see how that can happen. I just think what will happen is that Burgundy will just fall out of interest. Because it’s very hard to believe a wonderful Musigny or Chambertin made with Pinot Noir would work the same way. It won’t be the same vineyards as they won’t work the same with different grapes. So at the moment, I think it’s possible to manage with changes in viticulture and how you make the wine. But there will come a moment, if Greta Thunberg and others don’t get their way, and we don’t pay enough attention, there will come a moment when Burgundy will become compromised.

SB: Just going back to the pricing, prices for top Burgundy have risen inexorably over the past few years, fuelled in part by shorter vintages. Now you’ve made the point that some of the higher prices are down to the secondary market, not to what the producers originally charge. But either way is there a danger Burgundy will price itself out of the sphere for normal wine lovers, or is it fair enough for good growers to cater for the minority who can afford it?

JM: Yes, er…there are no short answers to this as so many parts of the supply chain involved. It’s fair to say in general that Burgundy hasn’t been seeking high prices, they’re not particularly commercial animals. However, once they see that the secondary market is delivering these really quite extraordinary prices…and we should say the great majority of the wine wasn’t sold at those prices, just a few causes circulate later on eg at auction. Then the growers start scratching their heads and saying: well hang on, if it’s leaving us at 100 units and then re-selling at 1500 units, what’s going on here?! It’s not that they necessarily want to make a vast amount of money themselves. Though some are keen to, for sure. They just say: why are speculators getting all this money in between? And it’s tricky to make the right decisions.

At the moment, there isn’t a sign of a slowdown I’ve been confidently expecting for a few years. I thought the lockdown and crisis would mean people would sit on their hands and stop spending vast amount on top wines. But auction market for latter 2020 has actually shown an uplift. It is discussed by producers in Burgundy and they aren’t particularly comfortable. They remember also they have a lot of long term customers, who’ve been buying for years or generations who can’t now afford the wines. And they feel uncomfortable kicking some customers out of the market place, and it’s an ongoing tension let’s say.

SB: I can understand. You cana understand, if people aren’t spending in restaurants, they’re maybe spending to drink fine wine at home, which nobody can criticise.

JM: I did a bit of that at home! Tidied up all sorts of single bottles that have been sitting there unloved.

SB: I’m gonna ask you about that in a moment. What about the new generation of Burgundian wine growers, who travel: how is that changing Burgundy and its wines?

JM: To some extent, again it’s multiple answers. We talk about a new generation but every year, with several 1000 domaines, several change hands. But I do feel there’s an active new generation that has come after my generation, which for a long time was considered the new generation for 20 years, you know, born late 50s: Lafon, Roumier, Grivot etc. But now there’s a group born in and around 1988, so 30ish, Charles Lachaux, loads of them, they’re taking things further. V ecologically conscious, looking at new ways to do viticulture, the travelling started before then, lots of French been to publicity events in the US or been around wine areas in California, New Zealand, Australia…learnt, also learnt what not to do, become much more alert to bacterial spoilage, for example. Lots of new young guys from New World countries come and do internships in Burgundy. Really good cross pollination, that counts a lot.

SB: What about organic and biodynamic. New generation more attuned to that?

JM: Very much so. Suddenly these last few years, lot more people getting certified rather than just practising it. A lot of growers of the retiring generation have been organic for 20-30 years but said no way getting certified. But as they leave office, the incomers are getting the certification, making it happen. And the big companies: Jadot, Bouchards, etc also getting on and doing it. So yes, very encouraging. Biodynamics too – increasing slowly. That’s more a philosophy more than anything so not so necessary to be certified. Natural too… And a lot are stopping using sulphur for vinification.

SB: So in one sense the New World bringing a cleaner sense of wine. On the other hand there’s a move towards a more natural, less interventionist approach. How do those 2 marry, and what’s the result in the glass?

JM: The cleaner means being aware of the aromatics of things like brett. You may have taken it for granted; now you’re told it’s spoilage. But then in terms of what might seem to be greater risk taking, it is to do with understanding the chemistry, biology, botany behind it. You realise you don’t need to have a blanket sulphur coverage – if you use less sulfur, the grapes or the wine uses its own protection. You have to survey it a lot more, be analysing all the way along, be totally on top of what you do, lot more man hours, but why wouldn’t you want to do that? And happily they do.

Eg nowadays with global warming, more people interested in using whole bunches or stems in vinifications of reds as they feel it freshens up the wines, even though it reduces acidity. But it also slightly reduces alcohol and leaves a fresher feeling. Now, one of the reasons people might not want to use stems is it theoretically gives a greener, more herbaceous aspect to it. But it’s probably the case that if you’re using sulphur during vinification, that’s when you leach out the herbaceous aspects from the stems. If you can vinify without using sulphur – you don’t have that. That’s just one illustration of many

SB: Fascinating! Thinking about smaller producers, we’ve seen vineyards and domains sell for millions of late to bigger corporate players – Clos de Tart, Clos des Lambrays, Bonneau de Martray. And French inheritance laws make things difficult for small scale family owners. Is Burgundy in danger of going too corporate, becoming more like Bordeaux?

JM: The Burgundians can be racist about people outside Burgundy, but they tend to hate people they’re afraid of. A long time ago, they were afraid of Americans. Now they can understand it’s fine. Then Japanese, now that’s fine. But corporate French companies and people from Bordeaux, they’re a bit frightened of. You named a few that were high profile, but you didn’t name all that many. And if you try to add, you could a few more, but not that many. So sometimes the case there are certain names changed hands, so underperforming before, it’s just a relief to have changes and have someone with proper financing who can make things better. What locals care about is it’s someone local Burgundian on the ground running the show. Ownership is less important.

SB: You’re famous for saying there’s ‘no such thing as making wine in a Burgundian style’, what do you mean by that?

JM: Burgundy has so many ways of doing things! It’s been one of its great strengths. Mr Parker never really worked out in Burgundy, I think many people would admit he and certain high level consultants, have at one period made too much Bordeaux taste too much in the same direction. That’s never really happened in Burgundy. Always been counter-currents. In one village maybe a few people going too much towards high oak or extract, but then the next door village would be going in totally the opposite direction. Or generations. Or families doing different things. So that’s what I feel about it. And I don’t quite understand…people using it for PR to say we’re making better wine than our neighbours cos we’re making it in a Burgundian fashion, but at the same time, you’d be touring in NZ, Oz, Cali. You’d also find people being pejorative about wines of the old country, saying our wines just as good, eg I’ve tasted my wines against Romanee Conti and my wines are better – I remember haring that in McMinville, Oregon in 1988!

SB: One final question – much of Europe and UK in lockdown. What’s your ideal lockdown wine? We’ll let you have one Burgundy and one wine from elsewhere.

JM: The great bottles of wine are those which you pour in the glass and you sniff and immediately *bing* you think: this wine could not have been better made. They can be baby wines or great wines. And that is the real satisfaction. One wine in 2020 that just made my jaw drop and I was able to get a 2nd. And it was just as good. It was pre-war, red Burgundy: a domaine wine from Louis Jadot. An unfamous vintage, 1938, and the appellation is going to stun you: Bourgogne Passetoutgrains. And it was just utterly gorgeous all the way through. It still felt as though you could separate the Gamay and Pinot out and see them working together. Isn’t that extraordinary?

SB: Still drinkable?

JM: Clearly an old wine, but it held together, had retained all component parts, not like a faded bit of history. Just two of us shared it after a 1964 Macon blanc.

SB: Something from somewhere else?

JM: We had during one of the Zooms a beautiful bottle of Californian Pinot Noir from my friend Jim Clendenen of Au Bon Climat, Knox Alexander Vineyard of I think 2011, it was incredible, sent an email to Jim after and he said: ‘I should hope so too!’ Miniature yields, been frosted. He worked out, for every single bottle of that sold, if you took his cost price, subtracted what he sold it for, he worked out it cost him $250 for every bottle he made of that wine! So I’m glad it was as good as it was!

Rebecca Palmer interview transcript

Rebecca Palmer (RP): Well I think Burgundy is just one of those great classic wine regions of all time that everybody would like to get to know and whose wines are just the most sublime wines ever really, when you actually end up feeling touched by a wine, moved by a wine, for me it’s always been Burg that has done that. They’re wines with perfume, elegance, they’re also refreshing – there’s just something about the greatest wines which can’t be touched.

Susie Barrie (SB): The idea that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir are capable of such extraordinary wines aren’t they?

RP: Yes extraordinary: in terms of their perfume, texture, body, they’re really quite extraordinary and Burgundy is able to create these styles which obviously get imitated around the world and very very well in lots of different cases but Burgundy is just something special and something apart.

SB: It is special but also very very expensive, are today’s prices sustainable, they’re gradually creeping up and up and they are pretty prohibitive for a lot of people.

RP: Not even gradually creeping up – I think there’s more than a gradual and there’s more than a creep going on. But certainly in the past decade in some cases certain wines, certain appellations, certain crus have more than doubled in price in terms of the actual ex-cellar prices that we as a merchant would buy at and that’s all about supply and demand from around the world and difficulties in terms of vintage variation and vagaries of climate but it is becoming v difficult.

SB: For an average person to afford Burgundy – if you were to say to someone who can’t afford Burgundy, where’s somewhere else, somewhere doing well?

RP: Well there are regions around the world and it depends what sort of style you’re wanting to try and in terms of regions that are aping the styles of the Cote d’Or, the Puligny, Meursault, the really top jewels, you may be looking at Hawkes Bay or parts of Australia, Adelaide Hills, or maybe Napa, Sonoma, in some cases. But you come back to Burg and you’re looking at villages that were perhaps in inverted commas considered lesser maybe in the south, Maconnais or premier cru Chablis which is still outstanding value for money, or some of the lesser villages like St. Romain, Hautes Cotes, rather than those really top villages which are for many of us, our customers and me included, are simply unapproachable now in terms of pricing. It just does become more and more difficult – exchange rates don’t help.

SB: And Pinot elsewhere in the world?

RP: Pinot well again NZ I would say, parts of Sonoma, especially the coast…

SB: It’s never going to be cheap is it? Decent Pinot?

RP: Never, obviously Oregon but again the prices are pretty impressive. But you can find really interesting Pinot now from Romania, southern France, there are pockets here and there but Burgundy yes wonderful but now it comes with a price tag.

SB: Just looking to the future, what is the future for Burgundy in the light of climate change. Things are getting hotter, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir bud early, so susceptible to spring frosts: is that a problem?

RP: It already is a problem and yes overall the temps are getting warmer but also there’s the problem of the timings, the length of the growing season, the susceptibilities but also the erratic weather events; hail at uncertain times of year, frosts maybe worse than ever before, and unexpected. That erratic, that volatility is particularly worrying. That can literally decimate a crop from one day to the next and we have to be realistic that there’s going to be more and more of that. Who’d be a vigneron, frankly?!