- Season 3 Trailer

- Fake Booze

- English Wine: Now What?

- How to Buy Wine

- Bordeaux’s White Bank

- We’re Making Wine for Hope & Glory

- WTAF – Wine’s Alt Format Warriors

- The Oz Clarke EXCLUSIVE!

- Our Wines of the Year

- Investing in Wine

- A Drink to Dry

- Coffee Dorks Meet Wine Nerds

- Burgundy 2020 Brief

- Getting to know the Côtes de Bordeaux

- The New Champagne

- The Magical Science of Taste

- Boxing Clever?

- Georgia 4 Ukraine

- On Natural Wine

- Fake Booze 2

- Adventures in Dosage

- Tasting 1982 Bordeaux

- Armenia’s Ambition

- The World’s BIGGEST Wine Competition

- Wine from the Arab World

- Why Bother Matching Food and Wine?

- Wine 4 Curry

- Wine 4 Roast Lamb

Summary

At one point, it looked like Covid was going to be the death-knell for Champagne.

And then…the bubbles bounced back. Big time.

But things aren’t quite the same as they were – in intriguing ways…

In this fascinating episode we catch up on all the latest hot topics from this famous and historic fine wine region in northern France with none other than legendary winemaker Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon of Louis Roederer (and Cristal).

And he tells us: ‘The 21st century is changing everything.’

So what exactly is the ‘new’ Champagne all about? On the one hand, it’s about admitting mistakes (sounds like the 60s and 70s have a lot to answer for). It’s also about risk and the potential rewards for pioneers.

We make sure to have a couple of glasses of delicious Champagne wines to hand – entirely for educational purposes, of course.

There’s talk of drinking glass pyramids, still wines, scallops, happiness, a tornado and the move from non-vintage to multi-vintage (yes, we do explain).

Life is too short for bland champagne! Do you agree?

Starring

- Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon of Champagne Louis Roederer

- Susie & Peter

Wines

- Louis Roederer Collection 242 Brut Champagne, 12% (£47-55, widely available inc Majestic and internationally)

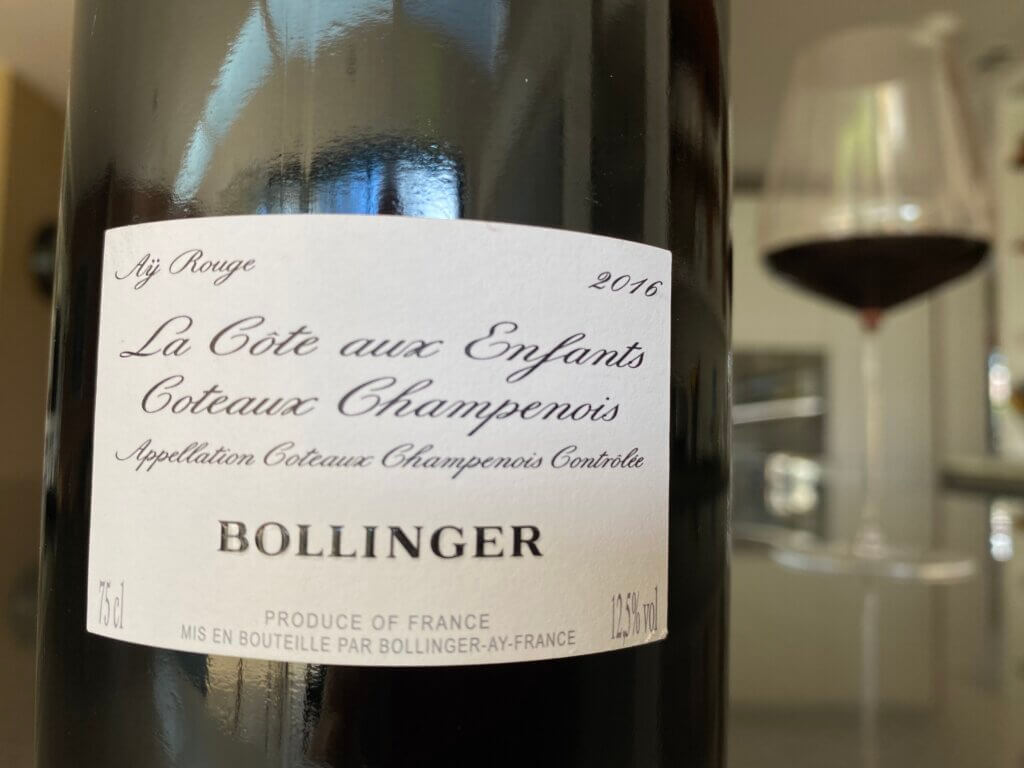

- Bollinger La Côte Aux Enfants 2016 Coteaux Champenois, 12.5% (c £75, Berry Bros & Rudd, Hedonism, Farr Vintners and internationally)

Interview transcript

Susie Barrie MW (SB): What’s getting you most excited in champagne right now?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon (JBL): What’s exciting in champagne, especially now, is the terroir really now speaking now more than they used to do in the 1970s, 80s. Probably due to the new generation of growers who want to be closer to natural practises or more terroir-driven practises. Less pesticides, more singularity, more identity from each plot, each place.

And we have a new generation that is really pushing the terroir further. So this is a very exciting moment. Within that frame, we also have climate change, which brings earlier harvests, which means riper fruit as well. And that is really giving us some material that is riper, more expressive, with more texture, with more of everything. And this is very exciting to work with this material now.

Susie Barrie: On that topic, you at Roederer have been working with organic and biodynamic viticulture since 2000, so over 20 years now. That’s quite rare in champagne, it’s not easy. Even now only 3-4% of the vineyard is organic, people have said it’s impossible in Champagne. How do you make it work, and are the wines better for it?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Let’s not forget that champagne, like all wine countries, have been organic up to the 1950s, 60s. It’s only since the 60s that we’ve switched to more pesticides less organic. So there’s been more time in the vineyard of France organic than non organic.

So when people say it’s not possible, it would mean that we are more stupid than our grandfathers who have done it for so many years! I hope we’re not that bad now, I hope we’ve improved our knowledge, that we’ve fine tuned our knowledge of the art of farming in Champagne, and we have the tools today, more tools more equipment, to be able to do it.

So it’s not that it’s not impossible, it’s just that it is possible, like everywhere. But it requires time, it requires knowledge, patience and it requires also to accept a part of risk in your viticulture and farming that there is a risk for sure but taking a risk is more rewarding in the end.

So I think the great wines of the world sit on the link between man and nature. This is a place, this is the people who live in this place, that make the magic happen. And this link has been a little bit lost in the last 50/60 years because of industrial, people looking outside. Now we understand we have to come back to our land, our territory and that we have to make them beautiful first. And if they’re beautiful they will make exceptional wines.

So it’s possible. It’s just a question of time, passion, money and of balance in your life. This is the idea behind – this is what I call the pursuit of taste. We went through the organic journey not to be organic but more to see how it would develop more taste to our grapes and wines. And we quickly saw that the organic farming was bringing a deep roots development, that was expressing the wines with lower yields, more concentration, more density in our wines. And this was making in the end a better wine.

Susie Barrie: Cristal is fully biodynamic. You’re saying there what it gives, you’ve said: more precision, definition. But how does that work, why does it give that?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: It works cos by going organic, you first stop disturbing the soils. We’ve been disturbing the soils since the 1960s using fertilisers, with nitrogen, potassium, calcium, bringing elements to the soils, water, that were in fact just elements.

The magic of our soils is that they don’t work just by elements. Elements are parts of a whole that includes proteins, insects, worms, bacteria, mushrooms, so many complex life in our soils, which makes a specific way of developing these nutrients available for the vineyards. And that’s what I call terroir. The way the ecosystem works.

Each time we’ve added some nitrogen, potassium, we’ve made the ecosystem work in a different way. Diluting the essence of the terroir. Let’s put it another way – if you bring what you believe is missing, in water and nutrients, then you always make the same juice. Which in the end is completely the opposite of the story of wine! I don’t say it’s bad. Because we have made some great wines under chemistry. But maybe it’s not as good as it could be.

Susie Barrie: Moving on to one of the most talked about issues of the moment, climate change. How is it affecting champagne?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: It is affecting Champagne, like all the world. Now. If you’re in Napa you see the fires. If you’re in Champagne you see more sunshine, more ripeness. But we were so much in the north of the limit of ripeness in Champagne that to date it’s beneficial – we get a benefit.

We get riper grapes, better grapes, healthier grapes, picked mid September instead of October. So in good conditions. So in the end it means we have a better quality of grapes. In wine, the quality of grapes makes the quality of wine. It’s been beneficial up to now. The question is: what it will do in the coming years – we have some ideas of 1.5-2 degrees Celsius within the next 20-30 years so that will change, that will change.

Susie Barrie: Will this involve changing grape varieties? I know Chardonnay’s robust but Pinot Noir can be tricky in a too-hot climate.

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: I don’t know. It’s not on my radar this because I think my position is that Pinot Noir comes from the Middle Ages. It’s travelled 1000 years to come today. It has seen the little cooling climate of the 1700s, it has seen some very dry years. What we have now are survivors of this generation of Pinot Noir that has adapted. So I think we have pretty adapted Pinot Noir. It’s just a matter of selecting it, helping it as a grower can.

So I understand we have to study this but for me I leave the change of grape variety to the Research & Development department. This is not in the farmers’ life. The farmers’ life is to adapt. And we have a lot to do on the soils, there are lots of solutions, just by giving more resilience to your soils.

We have the chalk in Champagne. I make coteaux champenois, which I pick very late, and I push the ripeness, and I still have so much freshness in these wines. So even in warmer conditions you can still maintain freshness, that’s why I call it the fight for freshness. It used to be the acid that was giving you an idea of freshness, now we have to find other ways of catching the freshness, and it is somewhere, in the soil, in the phenolics, in the winemaking as well, so we have to fine tune every little detail to maintain this freshness as much as possible.

Susie Barrie: Is one of those things MLF, malo-lactic fermentation, you haven’t done it in Cristal since 2008, to retain that freshness in a way that in the past, people did MLF and added more dosage to get rid of the acidity!

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Exactly. You have that everywhere. We don’t do MLF to keep the freshness. This is all about adaptation and being innovative, finding the right balance, the right tools to catch it. The great wines of the world today, if you study all those great wines, they are a natural handicap that mankind has taken advantage of. The best wines, the most singular wines, are not just coming easily from nature. They’re often a handicap that has been studied by man and man has adapted to take advantage of it.

Susie Barrie: Triumph over adversity.

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Exactly. I’m not a climate change sceptic. I can see it’s happening, I understand the challenge of global warming. BUT I remain in this spirit of taking advantage of the climate.

Susie Barrie: I’ve spent my career saying: The perfect base wine for a great sparkling wine is quite neutral, quite high acid, because then you do everything to it to make it the finished product. What you’re saying is: the grapes are riper. They’ve got more character. Does that mean that champagne’s inherent taste is going to change?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: It’s gonna change, it has always changed. Over time. The champagne 100 years ago is not the champagne of today. Pauillac 100 years ago is not the Pauillac of today. That’s always changed. The problem is that we always think in our lifetime experience. What you said: that a base wine should taste neutral, is the story of the 1970s. I can tell you that the 1959, 47, 45, 28s were super tasty. They were growing 3,000 kg per ha with more than 15,000 vines per hectare. That was really tasty! Really concentrated fruit! Picked at 13% alcohol, sometimes: 1959 Chardonnays were picked at 13% alcohol in Côte des Blancs, in Avize!

Susie Barrie: Wow – high!

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: And yet the 59s are some of the best champagnes ever made!

Susie Barrie: How do you explain that?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: What happened in the 1970s is what happened everywhere: we doubled, tripled the yields. And the wines were diluted. And we said: it’s about acidity and under-ripe grapes. But that’s the story of the 70s. I would love to have, and I’m lucky to have the archives of the house since 1832, I can see that, the chef de cave writing about the ripeness and what he was aiming for an so on.. And I feel that the ripeness we have to today, is the kind of ripeness they had in the 40s. It’s a change from the 70s but we are back!

Susie Barrie: Do you have a favourite match to a champagne with a dish?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Scallops carpaccio with Cristal. With a young Cristal at 10 year old. It’s just sublime. You get this saltiness singing and the acidity of the Cristal playing with the texture, the iodine, the sea salt. It works so well. This is always very exciting. Why do I like it so much? It brings me to a higher level of happiness. Because it’s very alive. There is a bit of the sea, a bit of our white soils as well. This is maybe the perfect life! To be somewhere…

Susie Barrie: that sounds a perfect life, scallops and Cristal! Who couldn’t love that?!

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: I won’t talk about Caviar and Cristal, which is a very good match too!

Susie Barrie: Let’s move on to your still wines, there seems to be an ever-growing number of still wines from the regions. You’ve recently launched Homage a Camille still wines. Can we expect more? Is this a growing trend?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Yes, I think it’s the final…when you have started to focus your art on terroir, and you see that it is bringing so much, the next step is for sure to encapsulate it as a single vineyard without the bubbles. Because then you get maybe the real expression, you don’t disturb the terroir identity by bubbles or dosage or whatever.

So if we started this idea of Homage à Camille, it’s because we wanted to showcase, like we did by the way, before, because the last bottling, we were making coteaux champenois at Roederer still wine every year, and we stopped in 1961. So we’re back to the story of the 60s, where we focused after 1961 on the bubbles, and we changed our farming for the bubbles. Now we are going back. And we can re-bottle these still wines like we always did, 50s, 40s.

In the 1960s each dinner or lunch at Roederer we started with sparking then we went onto still wines: from Cumieres, from Mesnil sur Oger. The idea is to come back to this terroir, to show what our terroir can give in a new winemaking, or new old, or different kind of winemaking. It won’t replace the bubbles for sure. But it does show where we start from: we start from terroir. And this is absolutely fascinating to see the freshness that’s left in these wines. We have this beautiful freshness whatever you do, even if you pick at 13.4%, you still have lots of freshness.

Susie Barrie: Would you compare – you’ve got the Chardonnay and the Pinot – describe the wines. Is the chardonnay in the Chablis mould? Or more Chassagne? Or is it its own thing? Is the Pinot Noir very light or with more muscle? How would you describe the wines you’re getting.

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: we are on chalk and chalk is the bedrock of our vineyards. So we always have the lightness of chalk. Which has nothing to do with the Côte de Beaune limestone of Chassagne or Puligny. So we’re not in the same game.

I think we have a specific lightness. There is a perfume, a lightness, and that’s a fascinating journey as well. Because you understand why we make sparkling wine so good, so light and so elegant despite the ripeness, because of our terroir produces that. And even if you pick super ripe without the bubbles, you get this lightness, this vertical perfume, that are unique for champagne.

Which is beautiful for Chardonnay and Côte des Blancs, it’s a pleasure because you play with fragrance. It’s a bit more touchy with Pinot Noir because you need to go for colour but not too much so I work a lot which whole bunch, full stem fermentation to try to get some density without pushing too much the extraction. You have to be careful extracting the tannins in those reds. And it’s a bit touchy. Probably because we have to relearn everything. Because we are re-learning how to handle the right oak for barrel ageing, how to extract it the right way, maceration all that, we start from a blank page because we’ve lost this for 60 years, we’ve not made any.

Susie Barrie: Recently you took a big step, you changed your NV Brut Premier, biggest selling wine, to MV blend, which is more expensive. “Desire for freedom’ motivated this. Can you explain the differences between Brut Prem and Collection 242, and what you mean by that desire for freedom?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: In the 70s, we always come back to the same moment, the 70s: very difficult weather conditions, very high yields, very green grapes. We had to build the ripeness from reserve wines. In fact, we have to correct the vintage. We called it a non-vintage. By blending different vintages, we were correcting the weakness of the most recent harvest.

So we thought about that and with the new conditions we have: beautiful years, much better grapes, it’s time to forget the non vintage and make a multi vintage. A multi vintage is more positive. It’s not trying to save the year by making every year the same taste. It’s to use the power of multi-vintage to make the best blend possible. This is why we identify each blend. Each blend now will be identified 241, 242, and so on, and it will be different. That’s the freedom I’m talking about.

I don’t stick to a recipe any more. My only goal is to make the best possible blend within what I have in the cellar at the moment I’m blending. So it’s not a question of keeping the same way.

I remember the 2002 vintage very well, maybe that was the trigger in my story for non vintage. All the wines in 2002 were so good, so vintage-like, as we say in champagne, because when a wine is good you say it’s a vintage, so that was so good that we had, when blending our Brut Premier, we had to decrease the quality, because it was too good. And it just doesn’t make sense for a winemaker to say OK, to be online with my previous blend and next blend, I decrease the quality of this exceptional child. This is exactly what we shouldn’t do!

Now, with the conditions we have, each new year is a new child and we can let him speak loudly, with freedom, more chardonnay one year because it’s a Chardonnay year? Let’s go for Chardonnay. If it’s Pinot Noir year, let’s go for Pinot Noir. That will remain Roederer because we make it. Because we source the grapes from the same locations. Because we have the idea of what is a beautiful elegant wine at Roederer and it’s what we fight and aim for.

But it will be singular, different. And it will be not a vintage. But it will have the versatility, the interest of a vintage. It’s a new blend. Let’s talk about the blend.

A non vintage is a brand. When you see Brut Premier, I love it but what about it? Not much. It’s Brut Premier. But with Collection 241, what’s the difference with 242, 243, there’s a discussion. I prefer 242, you prefer 243 – fine. At least there’s a discussion.

Susie Barrie: With non-vintage, the champenois have made a virtue of it: you can say to any customer it’s always the same, a house style, it won’t let you down, you know you like that house style. How do you take your customers with you if you change it every year? It’s the best wine but different each time, how to communicate this to your customers?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: It’s a challenge we have. Before, in 1970s, 80s when we crated non vintage, we had neutral base wine, so it was printed by the cellar: the yeast you use, the oak you use, the way you worked, that was the house style. So the wine was made in the cellar, not in the vineyards.

The 21st century is changing everything. We believe now that the wine has to come from the vineyards. The wine has to taste of vineyards, has to catch this sense of place, sense of territoire, of our story, what we do.

This is more than just a cellar and its flavour, great winemaker or chef de cave that has the taste buds to make it.

It’s more than that. It’s where we live, where our children grow, where we raise our children and families, so this is what we want to show: more than just the taste of the cellar.

SB: Can I just ask you for favourite champagne vintages to drink right now? Probably can’t afford 1959!

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: I like very much at the moment 2004. Really shining at the moment, it has what I call a window of beauty, which makes it just right now.

SB: Anything for the future? And vintages not released yet?

Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon: Some magic wines are coming! Really magic wines. I call it the golden decade, since 2007/8, we have in the cellar a better vintage after a better vintage. It’s quite amazing what we have in the cellar.

I’m not sure Champagne has ever had such a glorious sequence of vintages in a row, and so beautiful wines.