- Season 3 Trailer

- Fake Booze

- English Wine: Now What?

- How to Buy Wine

- Bordeaux’s White Bank

- We’re Making Wine for Hope & Glory

- WTAF – Wine’s Alt Format Warriors

- The Oz Clarke EXCLUSIVE!

- Our Wines of the Year

- A Drink to Dry

- Coffee Dorks Meet Wine Nerds

- Burgundy 2020 Brief

- Getting to know the Côtes de Bordeaux

- The New Champagne

- The Magical Science of Taste

- Boxing Clever?

- Georgia 4 Ukraine

- On Natural Wine

- Fake Booze 2

- Adventures in Dosage

- Tasting 1982 Bordeaux

- Armenia’s Ambition

- The World’s BIGGEST Wine Competition

- Wine from the Arab World

- Why Bother Matching Food and Wine?

- Wine 4 Curry

- Wine 4 Roast Lamb

Summary

Aghi Ourad is a Brit of Algerian descent who wants to change the way we think about wine from the ‘Arab world’ (his phrase).

Places like Algeria and Lebanon, where wine production has a surprisingly long history but currently operates in a challenging environment for religious, social or economic reasons.

Such wines from Muslim-majority countries, in Aghi’s view, are under-appreciated and yet offer great interest and value for wine lovers. So he’s set up a business, The Other Grape, to sell these wines and tell the stories of the people and places that make them.

Aghi has written movingly about suffering personal humiliation as a result of his ‘Muslim appearance’ and suffering from imposter syndrome with his own, European society. He’s also very honest about the ‘schizophrenic’ attitude to alcohol in Muslim-majority countries like Algeria.

We quiz Aghi about the relationship between Islam and alcohol, as well as the wines from Algeria and Lebanon today. We also dive into the fascinating wine history of these countries – did you know, for example, the following factoids?

- Algeria was once the fourth-biggest wine producer in the world.

- Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia accounted for two thirds of the world’s wine exports in the 1950s.

- Algeria was partly responsible for the development of France’s famous appellation contrôlée system.

Peter also reflects on his recent trip to Lebanon, to film for his new wine and travel show, The Wild Side of Wine, and shares his insights into the wine scene there.

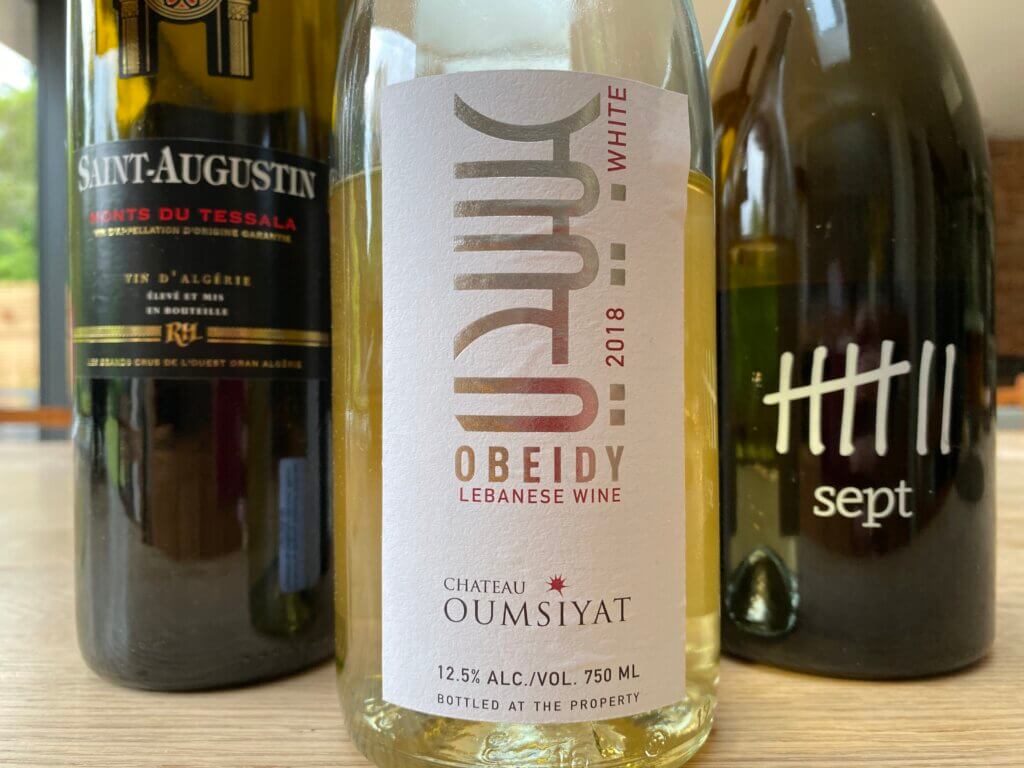

We talk indigenous grapes and unique wines, sampling a Lebanese Obeidy (white), an Algerian red blend from the Monts du Tessala, and a tiny-production Syrah from the Batroun hills of coastal Lebanon.

There’s also poetry in this episode, as well as talk of big guns, power cuts, Islamophobia, drones, phylloxera and what exactly constitutes an, ‘angry wine’.

We hope you enjoy the episode!

Oh, ps: you can get 10% off your order with The Other Grape if you use the discount code SP10.

Starring

- Aghiles (Aghi) Ourad, The Other Grape

- Susie & Peter

Wines

- Chateau Oumsiyat Obeidy 2018, 12.5%, Lebanon

- Saint-Augustin Monts du Tessala AOG 2017, 13%, Algeria

- Sept Syrah 2019 Batroun, 14.5%, Lebanon

Links

- Here’s a link to see the trailer and find out more about Peter’s new TV series, The Wild Side of Wine

- This is Alex Rowell’s book Vintage Humour: The Islamic Poetry of Abu Nuwas

- Here’s that piece on the poll of British Muslims cited by Susie in the episode

- Finally, do check out our previous episode on Lebanon (S1 E22) to hear from Chateau Musar’s Marc Hochar and Lebanese wine expert Michael Karam.

Aghi Ourad interview

Peter Richards MW: Algeria has a complicated relationship with wine. Britain has a complicated relationship, it’s fair to say, with immigration and racism. How are you aiming to reconcile all these problematic issues in what is an exciting wine business?

Aghiles Ourad: So it’s definitely an adventure! The way we try to do it is to really bring the human stories to the fore.

Wine production in this region does not follow the same storyline as wine production in Bordeaux or even in southern Italy like Puglia or Sicily, which resemble in many ways the same terroir, heat or pastoral nature of many of the countries on the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

The societal, human stories are very different.

In Lebanon we have economic and political crises that mean winemakers have to jump through hoops just to be able to produce their wine every year.

In Algeria you have seasonal workers who have pressure put on them by imams, or priests, to not work. By picking grapes it’s haram or illegal in the eyes of God and so you shouldn’t be doing this. But many of these seasonal workers are students who need the money for school and supplies.

So you have these dichotomies like that which raise a lot of questions that wouldn’t be asked in Europe.

This is one of the ways to show there’s no contradiction between the two. And we have a long way to go.

Peter Richards MW: I’m really interested in this, it’s not something I know much about: Islam and wine or alcohol. I understand there has been historically a lot of discussion about this. What’s your take? Can you be a good Muslim and drink wine or not? And what about the secular and economic issues?

Aghiles: The Quran makes a distinction between two different types of alcohol: nabidh and khamr. And so nabidh being the lighter one, khamr the stronger one.

And there were different schools of thought in Islam – that one is acceptable to drink and the other isn’t. Of course, today there isn’t the same distinction between the two.

But ultimately it’s a topic that deserves a lot more time to discuss! There’s a lot of space for academic study into this as well.

Ultimately we see the relationship between God and the person is one that’s vertical. So it really is up to the person whether they want to drink or not.

And the idea behind not drinking alcohol is because even the Prophet Mohammed’s companions went to pray next to him after drinking alcohol and they weren’t in the right state of mind to connect with God. So this is why you shouldn’t be drinking: because it clouds your judgement.

Of course, throughout time, different caliphates, different forms of Islamic government have been more or less tolerant to alcohol. It’s also been a good way to collect taxes, because these regions produce a lot of wine, alcohol, spirits.

Alcohol is an Arabic word as well: al-kohl.

So it’s one that for the past 14-1500 years still divides. Even today within different Muslim-majority countries, you see different attitudes towards alcohol.

So there is no right or wrong answer, it depends on the political system at the time.

Peter Richards MW: You also touch on the economics of it. There was French rule in Algeria and Lebanon. Obviously wine growing means labour, economic activity, taxation. What’s that aspect to it? Are we going to see a revival of wine in these countries, a muddling along of Muslim rule and wine production or alcohol as an important economic product and export?

Aghiles: This question very much depends on where you are.

Just to quickly connect Algeria and Lebanon – these are the two countries we started off with, The Other Grape is for now just a pilot but we are looking to expand to other countries – and within the same countries as well.

But the wine trade in Algeria and Lebanon follow the same trajectory. They were started with the international varieties we now know: Grenache, Carignan, Cinsault. These grapes that came from the Rhone and southern Europe were actually planted in Algeria and Lebanon by Jesuit priests.

And so the industry that exists today actually originates from these moments. And then of course it was the French in both Algeria and Lebanon that pushed these industries. And they provided for the most part the demand for wine. Algeria because it was a huge French colony; Lebanon was more a protectorate but still, French service-people were there to provide the bulk of demand for the wine.

Following the departure of the French, the Lebanese, because they have a strong Christian community, as well as Armenian (as you mentioned in your previous podcast), but also quite a cosmopolitan outlook, especially in Beirut, the Beiruti crowd love to party, quite French in that aspect!

Lebanon and Algeria followed different trajectories following the departure of the French.

Whereas in Lebanon the industry had existed, there had been a strong local wine industry making vin doux or sweet wine. Up until then the wine industry was happily carried on by Lebanese, people like Serge Hochar, started wineries when French were there then carried on afterwards.

With the Algerians it was different, it was more political. And in 1971 the president of Algeria actually uprooted most of the vines at the time, just to spite the French, they had a political spat. And at the time Algeria was still the fourth biggest producer of wine at the time!

So that’s the equivalent of Joe Biden taking a unilateral decision to uproot over half of America’s vines, because America is currently the fourth biggest producer of wine in the world.

So you see drastically different trajectories and that plays out into today’s outlook.

Lebanon has a vibrant, really quite dynamic wine industry that’s really promoting now indigenous grapes, they really see the importance of it to its economy. Whereas Algeria has been stuck in an oil-and-gas rut, classic hydrocarbons resource killers.

And now we have a few people like myself looking to diversify the economy. It’s really important for the survival not only of Algeria but same can be said of Tunisia and other countries as well, where economically you need to be pushing your own production.

Peter Richards MW: I’m interested in Algeria’s history. Lebanon we know: the Phoenicians giving the gift of wine to the world. But Algeria is not somewhere we talk a lot about in terms of wine history but at one point it was one of the world’s biggest wine producers…

Aghiles: Absolutely. Algeria is a fascinating place. It’s very hard to get to. But once you’re there you see all these structures, this architecture from political entities of the past. And part of this experience, especially if you go to the west, but everywhere in northern Algeria (but the west is ‘wine country’) you see old wineries, old colonial wineries, both abandoned and rehabilitated, still in use today. You see towns that were built around all these wineries.

So in Algeria the French made the economy go round on wine. It wasn’t their intention – they didn’t want their economies to compete with the mainland, and as we know the French were making a lot of wine, and they had actually tried to plant cotton and tobacco and all these colonial crops but they found the vine worked the best.

And so before Algeria became French (they entered 1830), was very experimental the first few decades. But it was in 1879 the phylloxera pest decimated French vineyards. And the one fact that came out of that – they were no longer self sufficient in wine. This is what really gave a boost to viticulture in Algeria.

So here you see, between 1880 and 1900 you see production go from 100m litres to 500m litres. And yeah so what we see is Algeria becomes the 4th biggest producer of wine in the world!

At its zenith, Algeria is producing over 2 billion litres of wine a year. On average it was just over 1 bn but it reached 2 bn. And they were comfortably the biggest exporter because most of it was ‘exported’ to France.

Peter Richards MW: So what was all this wine doing? I wasn’t around but you don’t remember many Algerian crus. Was a lot of it being blended into French wine?

Aghiles: Absolutely. So yeah, Algeria was 85% Muslim but it was the 4th biggest producer of wine in the world!

Most of it did go to France and it was known as vin de coupage. And it was blended with French wine just to add to the alcohol content, colour, make it a bit stronger. Because grapes that grow in hotter climates have more sugar and alcohol. So this was really the primary use of Algerian wine.

And fantastic side note is that this was one of the triggers that led to the appellations that we know them today.

Peter Richards MW: So in the late 19th century, when France ravaged by phylloxera, Algeria stepped into the breach to supply them with the wine they needed. But then fast forward to the 1930s the French said: well thank you very much we’ve worked out a way to get over phylloxera, we’re gonna create these laws that protect our wine, and you’re not welcome any more?!

Aghiles: Absolutely yeah. So what’s funny is that in Algeria they were one of the first to implement US rootstock, rather than chemical treatment. And there was a lot of fighting between them. But this mean they could produce and export a lot of the wine.

And this led to a bit of a diplomatic spat between a UK importer called Robert Leeky, this was the Robert Leeky affair, who claimed that Algerian wine, because it was used in vins de coupage with Bordeaux wines, was as good as Bordeaux.

So you can imagine the French wine producers, being as protective and restive as they are, really hated this. And so they fought to protect the identity of their wine from imitators. Which culminated in the appellations in the 1930s that we know today.

The impetus really came from Algerian wine! Because there was so much of it and it was mixed with Bordelais wine.

Peter Richards MW: Fascinating! Now you’re trying to revive this proud winemaking legacy of these countries. With The Other Grape, you call it a concept, hoping to roll out. If you’re gonna choose one wine that epitomises what you’re trying to do, what is it and why?

Aghiles: I’d like to go for an Algerian wine just out of personal preference but I’ll go Lebanese because it epitomises the search for identity.

This is the Obeidy grape, this is a grape used for centuries to make sweet wine in religious settings and churches. It was also a grape that was uprooted by the French when they first came, they thought it was harsh to work with.

But now we see a renaissance of these Lebanese indigenous grapes, turned into dry wine, and they add a totally different flavour profile than what you’re used to.

So Obeidy as dry wine retains that sweetness, creaminess character to it: you have hints of honeydew, perfect for people who prefer a not sweet but fuller bodied style white, like sweeter Riesling compared to a dryer white.

And it’s not just Obeidy but other indigenous whites like Merwah. These thing take a long time: you can’t just plant one and it grows and then you’ve perfected it.

The story of indigenous grapes is one that plays out over many years.

Peter Richards MW: You’ve go this wonderful business. You’re doing a magazine, which is great. You’ve published in this magazine a fantastic poem and I’d like you to share this with us. Maybe give it a tiny bit of preface as well.

Aghiles: This comes from a book by Alex Rowell, a British journalist, incredible person, called Vintage Humour; the Islamic Wine Poetry of Abu Nuwas.

And we were talking about Islam and wine earlier on. We could do many many episodes about that!

But essentially Abu Nuwas lived in 700s/800s, he was half Iraqi half Iranian today. And he was this quite incredible character who wrote poetry about debauchery, drinking wine, sleeping with both men and women, and we think about the first Islamic caliphates as being very religious. But in fact they partook in parties and drinking.

Abu Nuwas received state patronage from Mohammed Al Amin, an Abbasid caliphate. So he has a huge collection of poems called khammriyyat (wine poetry in Arabic is known as khammriyyat – even wine poetry in Arabic has a name so it goes to show how wine is pervasive in this time). And he’s not the only one – there are many, Omar Khayyam is another well known wine poet.

So I had this book and for this magazine we wanted to choose one of the poems we liked and put it in there and Alex graciously accepted. I can go ahead and read one for you, it’s my favourite:

Someone came to reproach me with an innovation

A plan of which I can bear zero toleration

Urging me off wine, because the fate of

He who tastes, it’s eternal damnation

These rebukers bring me nothing but resolve

To grant wine my lifelong dedication

Shall I spurn it, when God Himself hasn’t

And our own caliph shows it veneration?

Superlative wine, radiant and bright

Rivalling the very sun’s scintillation

While we may not know heaven in this life

Still we have paradise’s libation

So, critic, pour me one, and sing for me

For wine and I are siblings till my expiration:

‘Should I die, bury me next to a vineyard,

‘Whose roots supply my bones irrigation.’

Peter Richards MW: I’m not sure there’s much that can be added to that! Aghi – thank you very much indeed.

Aghiles: No worries! I want to add again that’s a translation by Alex Rowell so again thanks to him for that.

Peter Richards MW: Thank you!